The Long Beach premiere of Gavin Bryars’ opera, Marilyn Forever, has attracted a lot of media coverage. Poet Marilyn Bowering, who wrote the libretto, spoke to the Hollywood Reporter:

“Back in the late-1980s, Bowering was approached by a TV producer, who also happened to be named Marilyn, about collaborating on an unspecified project. Nothing ever came of it until the producer finally said, ‘My name’s Marilyn. Your name’s Marilyn. What about Marilyn Monroe?’ Out of that partnership came Anyone Can See I Love You, a series of Monroe’s interior monologues dramatized for BBC Radio and later reworked as a collection of poems.

Apart from being blessed with acting talent and ethereal beauty, Monroe had an intangible quality that made an indelible mark on the popular psyche. Bowering thinks it may have to do with a period in her adolescence spent living with her aunt Ana Lower, who introduced Monroe to the Church of Christian Science, where she remained a follower for eight years.

‘That teaching, which kind of puts you in charge of how you see the world and the world is made of love, had a real influence on her and made her this unusual person who didn’t seem to feel guilt about her sexuality,’ says Bowering. ‘It fed into this kind of idealism about love. There was an absolute kind of love, which would never be achievable and would turn out disastrously in real life, but there’s a sense she was always searching for these kind of ideals.’

Drawing on his early days as a jazz bassist, Bryars (who will sit in on bass for the March 21 performance) incorporates mid-century jazz melodies in his opera, sometimes referencing pop songs of the era. ‘Marilyn was a product of popular film and music,’ says Bryars about creating what director Andreas Mitisek calls ‘a meta-world reflecting on her life, career and relationships.’

‘My initial take is that’s really interesting,’ says Bowering about director Mitisek’s novel approach. ‘I think the whole process has just reminded me of the essential aspects of it, the bits. That’s poetry basically, the things that deal with human emotions. That is really what matters. And a lot of the other stuff, in any art form but particularly mine, can fall away and it doesn’t matter. But these things, which really are about how people feel, are all that matters.'”

Writing for the Long Beach Press Telegram, Timothy Mangan described the production in detail:

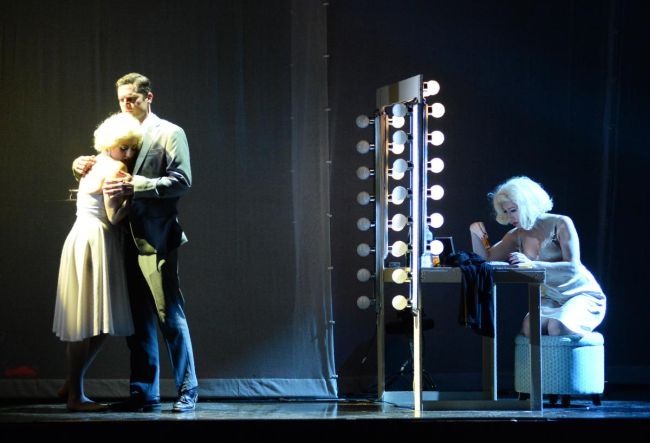

“The production and direction is by the company’s artistic director, Andreas Mitisek, and he took the liberty of dividing the lead role, Monroe, in two. Thus, we get a Marilyn in her bedroom, drinking, taking pills, recalling her life on one side of the stage, and a ‘public’ Marilyn, re-enacting those memories on the other. A single male role, Rehearsal Director, transforms into her several lovers (including Arthur Miller and Joe DiMaggio, though they are never named). A male duo, the Tritones, serves as chorus, commenting (sparingly) on the action.

Mitisek added live video, as well as some documentary footage, to the mix, all projected on scrims draped across the stage, creating an effective dream world. The division of Monroe worked well enough, but may not have been necessary. The part doesn’t always seem clearly split between the public and private character.

At any rate, soprano Danielle Marcelle Bond played the more private Monroe in a recognizable way, sensuous, nervous, making love to the camera. She sang sumptuously, expressively. Jamie Chamberlin gave the public Monroe a nice star-struck vulnerability, in shimmering tones, comfortable with the jazz. Lee Gregory sang the male parts with a fresh eloquence. Robert Norman and Adrian Rosales were the capable Tritones.”

Mark Swed reviewed Marilyn Forever for the Los Angeles Times:

“Live video projected large did help make each Marilyn more present, but the video also amplified the contrast between standard-issue upbeat and downbeat doppelgäangers. Watching the 80-minute performance, I kept thinking that the operatic Marilyn was given exactly the kind of typecasting that the real Monroe was trying to escape.

But Bryars’ score is her exit route…Bryars’ eloquent score has an overriding melancholic quality with an effortless flow between onstage jazz and the more symphonic style of the pit band. Vocal lines are all flowing melody, mostly unresolved. Period-style pop songs in the style that Marilyn might have sung emerge in and out of the general musical material, as though moods of Marilyn, although Bowering’s pop lyrics miss the Tin Pan Alley zing by a mile.

The maudlin Marilyn here dims the light of the bright Marilyn. The true Marilyn was both, and her allure wasn’t, as it feels with this text and this staging, mimickry. With the help of Bryars’ bluesy wonder, very good singing throughout and Bill Linwood’s expert conducting, Marilyn struggles to come alive. Just as she did so sadly, yet so wondrously, in real life.”

Writing for L.A. Weekly, Christian Hertzog was more critical:

“Marilyn Forever sounds like the title of a campy revue at the Cavern Club, but Long Beach Opera’s production at the Warner Grand Theatre in San Pedro is a morose meditation on stardom, sex and self-destruction.

Unfortunately, this U.S. premiere never comes together. Is it the fault of Marilyn Bowering’s vague libretto, a jumble of half-factual, half-imagined episodes from Monroe’s life? Could it be 80 nonstop minutes of Gavin Bryars’ brooding, amorphous music? Is it director Andreas Mitisek’s unclear telling of the story, or his bizarre decision to split the role of Marilyn between two singers?

Bowering’s libretto is a memory play. Monroe lies dying on her bed, incidents from her life oozing through the barbiturate fog — a late arrival at a studio, an inability to sing (or act?), a boudoir scene with a man (possibly Arthur Miller), a mysterious booty call.

Is the libretto too ambiguous for its own good, or does it have latent possibilities for creative staging? Hard to tell here, as Mitisek’s design and direction either disregarded the libretto’s instructions or did a poor job rendering them comprehensible.

Mitisek divides the single role of Marilyn into two separate parts: overdose-suicide Marilyn (portrayed by Danielle Marcelle Bond) and past-memories Marilyn (Jamie Chamberlin). This drains the lead part of its bipolar showmanship. The role should spotlight a singer’s acting skills as she bounces back and forth from woozy, dying Marilyn to sex symbol or troubled wife.

The libretto uses familiar iconography: Monroe as an insecure woman whose radiant sexuality blinded men to her other traits. Bryars gives Marilyn’s part no compelling melodies, and the musical differentiation between her dying and lively personas is too subtle. To do justice to this character requires a singer with a dazzling, oversized voice and a magnetic stage presence.

Chamberlin possessed a firm, focused voice, but there was no brilliance to it. Her acting didn’t exaggerate enough the feminine qualities of Marilyn, winding up a mere simulacrum of Marilyn’s potency instead.

Bond’s voice had a bit more oomph, and she sold us on the pathetic, fading Marilyn, but it’s unclear if she could shift dramatically and vocally into the powerful movie star, if she were to one day inhabit the full role.”

One Reply to “‘Marilyn Forever’: The Critics’ Verdict”