David Crow digs deep into the ‘Diamonds’ homage in Birds of Prey, the new Harley Quinn movie produced by and starring Margot Robbie, over at Den of Geek.

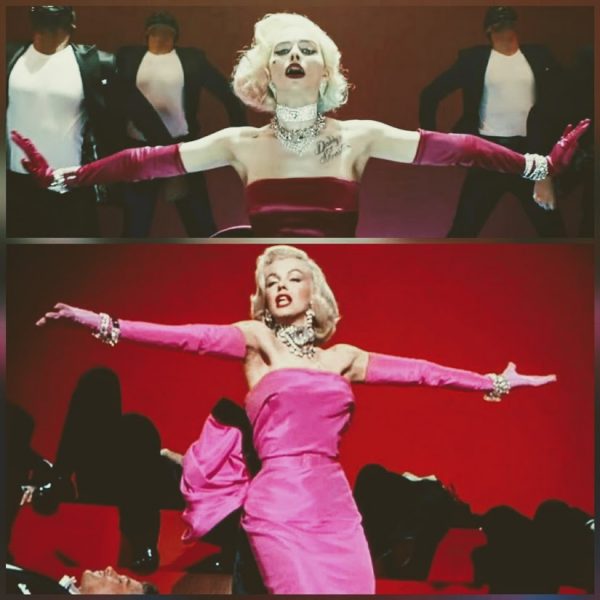

“Robbie’s Marilyn Monroe homage has been at the center of Warner Brothers’ Birds of Prey marketing, from trailers to official clips. After all, what else says this ain’t your typical superhero movie than a ‘50s inspired musical number? And while it’s only a brief sequence in the finished film, it’s also one of the movie’s best moments. Tied up at the nightclub owned by Roman Sionis, the villainous Black Mask (Ewan McGregor), Harley has been captured simply because he believes she’s more vulnerable after her breakup with the Joker…

But Harley is neither silly or in need of protection. She quickly realizes that Black Mask is after a MacGuffin of great importance—a diamond, in fact—and Harley will be just the gal to retrieve it for him. Because Harley is resourceful, Harley is smart… and Harley is also a wee bit nuts. Hence when Sionis smacks her in the face, Harley vanishes into a musical fantasy where she gets to go into full Marilyn mode, vamping in pink attire and bejeweled accessories while singing ‘Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend.’ McGregor even shows up in the fantasy to dance along before shooting up the scene much too quickly.

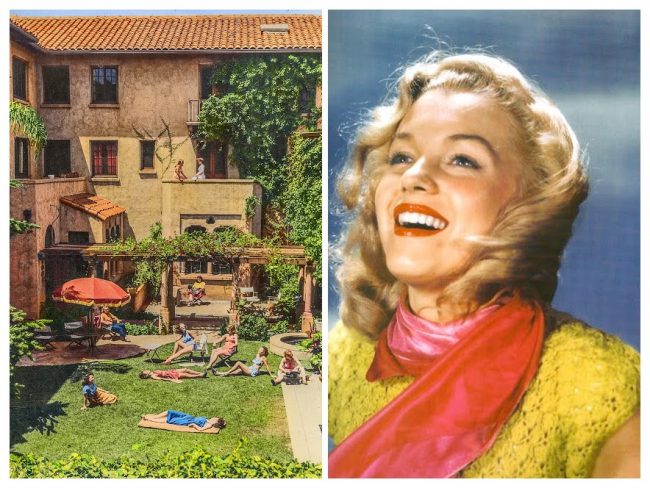

But this is more than just an homage to a Marilyn Monroe scene or the abject cynicism of her song …. In the original movie, the song is a third act statement of intent by Monroe’s character, Lorelei Lee … Breaking into Hollywood because of her beauty and sudden success as a pin-up model during World War II, Monroe eventually signed multiple contracts with Fox before she became the defining image of a 20th century blonde bombshell and movie star sex symbol.

She didn’t necessarily want to be that—or certainly only that. Having a contentious relationship with studio head Daryl F. Zanuck, who disliked Monroe and her desire to be more than the dumb blonde gold digger in musical comedies, she was suspended in 1954 for refusing to do The Girl in Pink Tights. She eventually made up with Fox, but she also started her own production company, Marilyn Monroe Productions …

During this era, Monroe also struggled in her private life, including her marriage to Joe DiMaggio, the world famous baseball player …. Again the press took a disdainful sniff at the movie star who let the strong man get away—just as they sneered when she then married intellectual playwright Arthur Miller.

… The story of Monroe’s fight for credibility, both in association with 20th Century Fox or with Joe DiMaggio, and away from these men, is the kind of real world struggle Birds of Prey strives to reflect, even in its gonzo funhouse mirror … everyone, including other women, define Harley by her relationships to men, and view her to be, as one man says early in the film, ‘a dumb slut.’ These insults are hurled even though she has a PhD and, as she displays throughout the film, a rather quick witted intellect in which she can psychoanalyze her friends and foes alike.

Through it all, she struggled for legitimacy and respect as an actress when executives were content to just see her singing ‘Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend’: a male fantasy in which a beautiful woman purports the only thing she wants in this world are the presents powerful men can bestow on her.

In her lifetime, Monroe was likewise defined by the men in her life and what they could give her …Nevertheless, playing that game gave Monroe the tools to eventually make movies she was proud of, like Bus Stop, and to form her own production company—which was a crack in Fox’s power over her and another crack in the slowly crumbling Hollywood studio system…

That is exactly what Margot Robbie did after she realized the potential of the Harley Quinn character. Perfectly cast as the jester moll, Robbie’s Harley was the sole redeeming quality of Suicide Squad (2016), even as director David Ayer’s camera seemed to most value her for all the lingering shots of her skintight (or nonexistent) clothing. Nonetheless, Suicide Squad gave Robbie a lot more clout as a producer …

Robbie herself revealed last year that she actually loathes when journalists, usually men, describe her as a bombshell. ‘I hate that word,’ Robbie told Vogue in June. ‘I hate it — so much. I feel like a brat saying that because there are worse things, but I’m not a bombshell.’

One might suspect that in her time, Monroe thought similarly as Fox kept trying to cast her in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes type roles … But using the tools Monroe pioneered, Robbie is able to take preconceptions audiences might have for her, or for Harley Quinn after Suicide Squad, and blow them away.”