“Yet it’s clear from Miller’s screenplay for John Huston’s movie The Misfits—a film celebrating its fiftieth anniversary this year—that Miller didn’t see the American family as a problem that had an answer. Flee the traps of family life on an Eastern stage, and you might find yourself wandering lost and mangled in a film set in the deserts of Nevada, atomized and disconnected, drifting among strangers from divorce court to highway to rodeo to whiskey bottle to bed with fast friends. The myth of the family and the myth of self-reliance—how does the same culture hatch two such irreconcilable dreams? Miller’s characters are always being crushed by conflicting motives and impulses, forced into impossible situations by self-delusions or the repression of past betrayals. In his Eastern plays, blood relations doom one another, acting like planets circling closer and closer to moral black holes. In the movie script that heralded the end of his marriage to Marilyn Monroe, absolute freedom from family ties in the West appears to be another kind of American disaster—one papered over with a Hollywood ending.

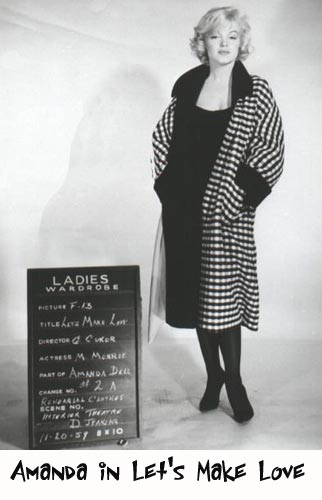

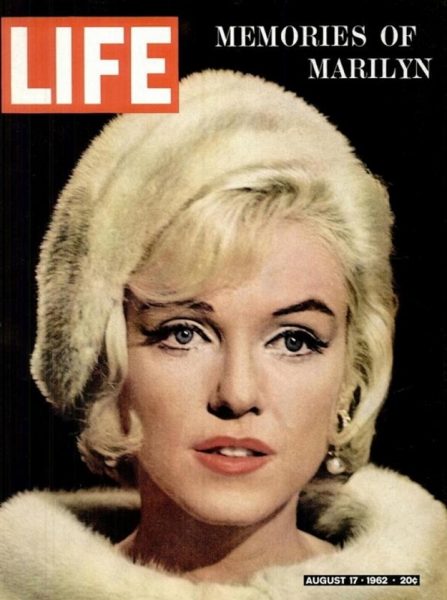

Bigsby [Christopher Bigsby, Miller’s biographer] suggests that the playwright may have been drawn to Marilyn Monroe because the star, like Miller’s father, had been an abandoned child, and also notes the curious fact that Monroe and Isidore continued to socialize after her divorce from his son. In one sense, Monroe had been searching for a substitute father all her life—many of her lovers were older men, including Miller. According to Joyce Carol Oates’ fictionalized version of her life, Blonde (2000), she had grown up thinking that an image of Clark Gable in her mother’s home was a picture of her long-lost dad, and this stunningly imagined episode from the novel is based in fact. An irony of fate that also foreshadowed doom brought them together in 1960 to play lovers on the set of John Huston’s filmed adaptation of The Misfits. Miller had written the screenplay to honor Monroe, but their marriage collapsed on the set.

‘Hello’ was one of Miller’s keywords in the 1960s. It reappears at key points in The Misfits, as in the famous moment when Roslyn calms down Guido after spurning his advances by saying, ‘Hello, Guido!’ It’s also the final line of dialog in Miller’s 1964 play After the Fall, where it denotes a much more hopeful potential for the characters Quentin and Holga, modeled on Miller and his third wife, Inge Morath, to find each other in the ruins of twentieth-century history and the fracturing of families and marriages. (Miller and Morath first met on the set of The Misfits.) Hello: it’s an all-purpose interjection with an American ring to it. It’s ready-made for a country of ‘interesting strangers,’ as Isabelle calls Reno in The Misfits. It can be a question or a statement that amounts to admitting that we don’t know one another and we aren’t family: ‘Yes, I’m here, I exist, and who might you be?’

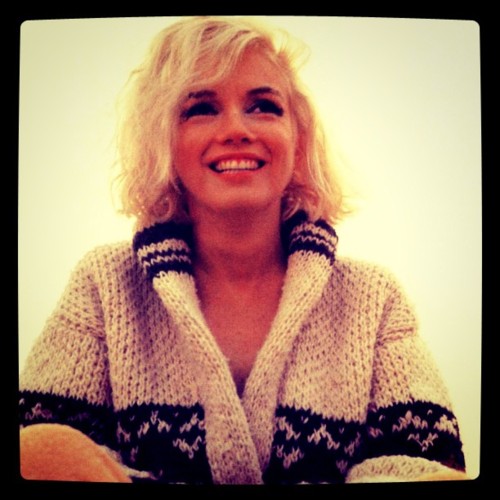

‘Don’t you have a home?’ Roslyn asks Gay when they’re driving around. ‘Sure,’ he says, ‘Never was a better one, either.’ ‘Where is it?’ ‘Right here,’ Gay says, and nods at the road and out at the desert. The camera shows us a stretch of land blurred by the speed of the drive: scrub brush, sand, and mountains. Sometimes the land looks grand, sublime, and inviting; on other viewings, it seems sadly desolate and empty, a kind of lie. Anyone who has ever been to Nevada knows the feeling of being divorced from everything, stuck between two sets of mountains, the time zones piling up between you and your family, everyone you once loved, and everything that once loved you. Roslyn’s response to Gay’s childlike faith in the open country—a place where you can ‘just live,’ as he puts it in an earlier scene—seems to open into a void. Monroe’s face conjures a movie star’s well of loneliness, a wounded look that seems to stare out from the foster homes of Norma Jean’s own childhood.

‘I don’t feel that way about you, Gay,’ Roslyn says, and the next thing you know he is kissing her awake for breakfast. Eroticism becomes the great American balm for lonely hearts, the fake cure-all from the movies, from Marilyn. The characters in The Misfits try to fabricate an artificial tribe out of the magic dust of sexual alchemy and instant friendship in a broken-down void that isn’t even a frontier anymore. In the East, Miller’s characters cannot escape their fates because of their closely knit families, or because of events that loom out of the past to entrap parents and children. In the West, Miller’s characters are completely free but also completely unstuck, there’s too much room and nobody knows what to do. Maybe the East contains too much love and the West not enough—absolute freedom can be as terrifyingly lonely as family life can be cloying. At any rate, there’s no solution anywhere; the signs leading to the freeway or back home are pointing in different directions. ‘Well, you’re free,’ Isabelle toasts Roslyn near the beginning of the film. ‘Maybe the trouble is you’re not used to it yet.’ Or maybe the real trouble is that the heart cannot stand this kind of freedom.

The Misfits is regarded as an artistic and personal death-trap: in Hollywood lore, it is the picture that destroyed Miller’s marriage with Monroe through various infidelities, behind-the-scenes dramas, and on-set disasters. In fact, Monroe already had entered the abyss for good and would not complete another picture. After insisting on performing many of his own strenuous stunts in the desert heat, Gable died of heart failure soon after filming ended. Yet unlike the real-life background of the production, and very much unlike Miller’s best plays, the movie itself is desperate to conjure magic and restore belief in the possibility of a happy ending. ‘Gay,’ Roslyn says, ‘if there could be one person in the world—a child who could be brave from the beginning…’ Monroe had miscarried twice with Miller. According to Miller’s ‘cinema novel’ version of The Misfits, ‘The love between them is viable, holding them a little above the earth.’

We want to believe it can all work out, and so does Miller, at least he does here. This is sorrow-tinged, impossible wish-fulfillment, not just another manipulation cooked up by the studios. The Misfits is one of those movies that jumps right out of its frame, telling us almost everything we need to know about the movies, about the insecure relationship between writers and Hollywood, about what happened to the West, and maybe even about how the American Dream had gone wrong. Happy ending aside—Joyce Carol Oates in Blonde calls it a ‘fairy tale’—the movie contradicts itself. Actually, it doesn’t contain a lot of good news.

The Misfits’ portrayal of double-edged freedom from family ties in the West couldn’t be further removed from the tragic irony of the Lomans’ ‘free and clear’ home ownership that draws the curtain in Death of a Salesman. When asked about his home, Gay gestures outside his truck at the desert. It’s the place that he’s taking Roslyn in the Hollywood happy ending of The Misfits. She’s told him that she’s ready to start a family. But, really, is there any reason to suspect that it will last longer than Gay’s previous marriage, the children of which run into their falling-down-drunk father at a rinky-dink rodeo? (Or any longer than Miller’s own marriage to Monroe, for that matter?) An Eastern family might be a self-poisoning well or a fouled nest, but The Misfits raises questions about what happens to American souls when they achieve the national dream of breaking loose from all moorings and drifting into a vast continent where nobody’s home. Which is a worse fate, to have a bad family or to have no family at all? The ending of The Misfits gives us a false or movie-dream solution to an enduring problem. It’s an answer we want to believe in but which we know is a temporary shelter at best, at worst a mirage—a mirage that surely will lead to the production of one more unhappy family.”