All About Eve and Niagara will be screened on US television as part of TCM’s Salute to Fox, airing on July 24 and again on July 31, Laughing Place reports.

Marilyn Monroe 1926-1962

All About Eve and Niagara will be screened on US television as part of TCM’s Salute to Fox, airing on July 24 and again on July 31, Laughing Place reports.

Alexandra Pollard takes a fresh look at Marilyn’s ill-fated last movie, Something’s Got to Give, in an insightful piece for The Independent.

“She hadn’t been on a film set for over a year when she was cast in Something’s Got to Give, a remake of the 1940 screwball comedy My Favorite Wife. Her time off had been plagued by illness and drug addiction … The accumulative physical toll had caused her to lose so much weight that she was thinner than she had been in all her adult life. The studio, Twentieth Century Fox, was delighted. ‘She didn’t have to perform, she just had to look great,’ said the film’s producer Henry Weinstein, ‘and she did.’

But in hindsight, Monroe wasn’t ready – either physically or mentally – to return to acting … ‘She was just fearful of the camera,’ said Weinstein, who recalled Monroe throwing up before scenes. Early on, he found her unconscious, in what he described as a barbiturate coma … The studio and production team had little sympathy for their star. ‘Yes this is a sick woman,’ said screenwriter Walter Bernstein, ‘but this is a movie star who’s getting her way, and who doesn’t give a damn about anybody else, and is being destructive and self-destructive.’

But watching Something’s Got to Give’s raw footage – most of which remained unseen for years after the film was scrapped – gives a very different impression. On camera, Monroe is earnest, demure, desperate to get her part right. If she messes up, she apologises profusely … She is gentle with her young co-stars, too. Alexandria Heilweil, who played her five-year-old daughter, is told to sit up straight. ‘If I do the right thing…’ says the little girl, but [George] Cukor cuts her off: ‘Be quiet.’ Monroe smiles at her. ‘You will,’ she says gently. It certainly doesn’t seem like the behaviour of someone ‘wilfully disruptive’.

And there were a few good days. During the now (in)famous swimming pool scene, Ellen takes a late-night skinny dip, attempting to lure her husband out of his bedroom. The set was closed, but a few select photographers were allowed to stay. When Monroe ended up removing the flesh-coloured swimming costume she had been given, they were caught completely off guard. ‘I had been wearing the suit, but it concealed too much,’ she later told the press, ‘and it would have looked wrong on the screen… The set was closed, all except members of the crew, who were very sweet. I told them to close their eyes or turn their backs, and I think they all did. There was a lifeguard on the set to help me out if I needed him, but I’m not sure it would have worked. He had his eyes closed too.’ Photos of Monroe emerging from the pool, sans suit, appeared on magazine covers in over 30 countries. By all accounts, spirits seemed high.

But things went rapidly downhill. On 19 May 1962, having been too sick to work for most of the week, Monroe flew to New York for President John F Kennedy’s birthday celebrations … Monroe had gained permission to attend the event long before filming began, but [Cukor] deemed it unacceptable. In June, just a few days after Monroe’s 36th birthday, she was fired for ‘spectacular absenteeism’, and sued by Fox for $750,000 for ‘wilful violation of contract’. ‘Dear George,’ wrote Monroe in a telegram to Cukor, ‘please forgive me, it was not my doing. I had so looked forward to working with you.’

In fact, it may not have been entirely Monroe’s doing. At the same time as Something’s Got to Give was being made, Fox was haemorrhaging money on its three-hour epic Cleopatra … The studio was panicking. ‘Tensions were high, nerves were frayed, funds were low,’ wrote Michelle Vogel in Marilyn Monroe: Her Films, Her Life, ‘and it’s clear that Something’s Got to Give and Marilyn Monroe were the scapegoats for some very anxious studio executives who felt they were spinning out of control with both productions. The lesser of the films had to go.’

A few days before she died, Monroe had given an interview to a journalist from Life Magazine, and the subsequent profile was published a few weeks later. It ended with the following: ‘I had asked if many friends had called up to rally round when she was fired by Fox. There was silence, and sitting very straight, eyes wide and hurt, she had answered with a tiny, “No”.'”

All About Eve is (rightly) included in Indiewire‘s list of 40 films that defined 20th Century Fox, which has now officially merged with Disney. However, I think Marilyn’s string of hits at the studio – such as Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and The Seven Year Itch, to name just two – also merit consideration.

“Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve (1950) made 20th Century Fox the crown jewel of Oscar players when it nabbed a record 14 Academy Award nominations and won six prizes, including Best Picture. The drama is the first film to earn nominations in all six major Oscar categories: Director, Picture, Actor, Actress, Supporting Actor, and Supporting Actress.”

Following last year’s Disney buyout, 20th Century Fox was officially dissolved this month, as Peter Bart reports for Deadline. While Marilyn’s feelings for her home studio were mixed at best, it’s a bittersweet moment in movie history.

“Hollywood endured a big setback this month, and it had nothing to do with the Oscars. A major studio, 20th Century Fox, officially disappeared into the mist, instantly transforming a once robustly competitive industry into a Disney oligopoly. The ultimate cost in jobs could range as high as 10,000, but the real cost will be in opportunity and competitive zeal.

Fox’s history, like MGM’s, has wallowed in melodramatic triumphs and scandals –the corporate intrigues of Warner Bros and its corporate parents (AT&T) or Universal (now a child of Comcast) seem pedestrian compared with Fox’s operatic struggles: Marilyn Monroe’s mysterious demise in the middle of Something’s Got to Give; Elizabeth Taylor’s over-the-top theatrics in Cleopatra; Darryl F. Zanuck’s eight-hour stockholder speeches and stormy battles with his son and successor, Richard (fired in 1971); the eleventh-hour brink-of-disaster deal for Star Wars; the fierce tug of war over Titanic and its overages [overspend].

Given its history, it’s fitting that this is the only studio immortalized in a rock ‘n’ roll classic (‘Twentieth Century Fox’), performed with drugged-out vigor by Jim Morrison and The Doors.

Even Fox’s beginnings are cloudy: It may, or may not, date back to 1915 with the birth of Fox films, but also to 1935 when the mysterious Spyros Skouras orchestrated the first of several mergers. Darryl Zanuck, who felt he was a bigger star than his actors, gave sizzle to the studio with signings of Tyrone Power, Henry Fonda, Alice Faye and Betty Grable but also gave it gravitas with such well-intentioned movies as Gentleman’s Agreement, The Razor’s Edge and Wilson. Production of The Longest Day in 1962 was the ultimate Zanuck epic — a long, lugubrious account of the D-Day Invasion with just about every star in the world popping up in bit roles (John Wayne and Kirk Douglas among them).

True to studio tradition, it remains unclear how much of the Fox identity may emerge following Disney’s $71.3 billion seizure … If Fox filmmakers feel angst, it is understandable. Disney accounted for 26% of the box office last year and that could rise to 40% this year … Darryl Zanuck is no longer around to bark, and no one seems to be mounting a new Cleopatra, but somewhere on the emptying Fox lot fragments of history still reside.”

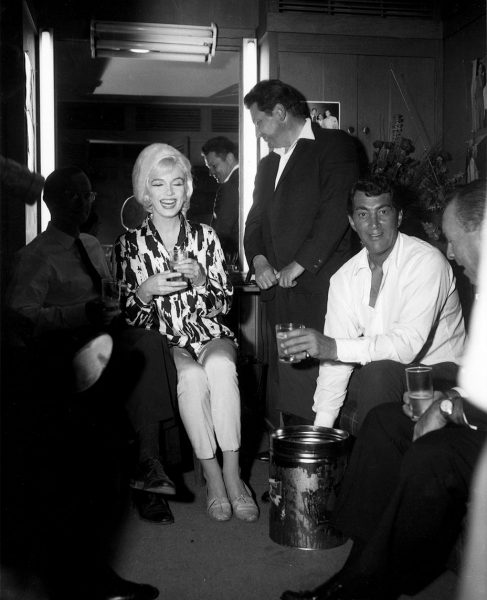

In some ways, Rock Hudson was Marilyn’s male counterpart as a misunderstood sex symbol of 1950s Hollywood. They partied together at the How to Marry a Millionaire premiere in 1953, and in 1962 Rock would present Marilyn with her final award at the Golden Globes. Sadly they never worked together, but Rock was the initial favourite for her leading man in Bus Stop; and in 1958, she was considered for Pillow Talk before deciding to make Some Like It Hot instead. (Doris Day got the part, the beginning of a great comedy partnership with Rock.)

Until now, it has been unclear how well the two stars knew each other (although a recent hack tome made the unlikely claim that Marilyn and Rock were lovers – as we now know, Hudson was gay.) In a critically praised new biography, All That Heaven Allows, author Mark Griffin draws on interviews with Rock’s secretary, Lois Rupert, who claims they often spoke on the phone. Although the frequency of their conversations may be questioned, the obvious affection of their Golden Globes photos combined with this information could suggest that Rock was one of the few Hollywood figures trusted by Marilyn in her final months – and Griffin also reveals that Hudson generously donated his fee for narrating the 1963 documentary, Marilyn, to a cause very close to her heart.

“It was while he was on location for A Gathering Of Eagles that Rock received word that a friend had died. As Lois Rupert recalled, ‘Rock met me at his front door with the news … “Monroe is dead” is all he said.’

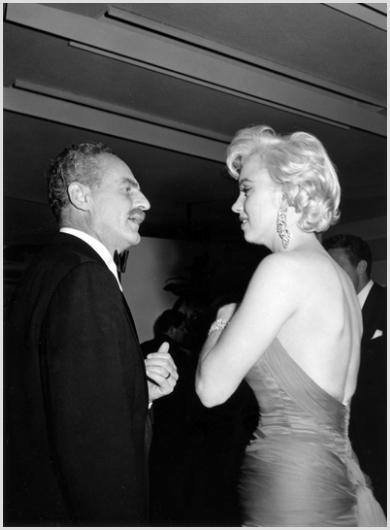

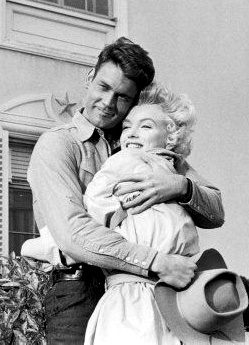

Only five months earlier, Rock and Marilyn Monroe had posed for photographers at the annual Golden Globes ceremonies. In images captured of the event, Monroe, who was named World Film Favourite, is beaming as Hudson enfolds her into a protective embrace. With a shared history of abuse and exploitation, it was inevitable that these two should be drawn to each other. Recognising that he posed no sexual threat to her, Monroe had latched on to Hudson and had lobbied for Rock to co-star with her in Let’s Make Love as well as her uncompleted final film, Something’s Got to Give.

Lois Rupert remembered that in the early 1960s, Rock regularly received late-night distress calls from Monroe as well as another troubled superstar. ‘If it wasn’t Marilyn Monroe crying on his shoulder, then it was Judy Garland,’ Rupert recalled. ‘It was almost like they took turns. Marilyn would call one night and Judy the next. He was always very patient, very understanding with both of them, even though he wasn’t getting much sleep. I think he liked playing the big brother who comes to the rescue.’

Within ten months of Monroe’s death, 20th Century-Fox would release a hastily assembled documentary entitled Marilyn. Fox had initially approached Frank Sinatra about narrating, but when the studio wasn’t able to come to terms with the singer Hudson stepped in. Hudson not only provided poignant commentary – both on and off camera – he donated his salary to help establish the Marilyn Monroe Memorial Fund at the Actors Studio.”

Although he wouldn’t gain his first screen credit until 1965, Earl R. Gilbert began his career at Twentieth Century Fox in the same year as Marilyn (and at the same age.) In an article for Variety, James C. Udel looks back at Gilbert’s long career.

“Back in the age of directors calling ‘Lights, camera, action!’ lighting was an unsung craft. One crew member who raised the bar, employing natural-looking illumination like an artist uses his brush, is gaffer Earl Gilbert.

Gilbert was born in Bakersfield, Calif., in 1926. His father, Ray, an electrician at Twentieth Century Fox Studios, helped Earl obtain union status via ‘the sons of members’ provision. Joining in late 1946, Earl aced a grueling four-hour test pulling pound-a-foot cable 60 feet above the stage.

Serving as a rigger on pictures Forever Amber and Gentlemen’s Agreement (both in 1947) and The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Gilbert first demonstrated a talent for lighting on Elia Kazan’s 1952 Viva Zapata!

Continuing with Fox into the 1950s, Gilbert helped light classics such as The Robe, two Marilyn Monroe starrers — Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Bus Stop … On Blondes, he recalls Monroe being shy but Jane Russell being gregarious: Russell’s cry of ‘Howdy, Earl!’ each time she greeted him on set, he says, made him feel like a million bucks.

Gilbert developed the art of using available location lighting. He ‘borrowed’ electricity by scaling telephone poles and tapping into overhead power lines — a gambit that risked electrocution.

Now retired and interviewed by Variety in his comfortable home in Thousand Oaks, Calif., Gilbert reminisces … ‘I never used a light meter,’ he allows. ‘If it looks good, it is good, and if it’s not, fix it!'”

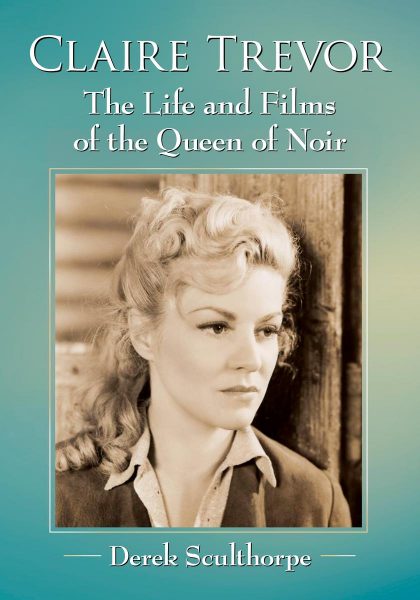

While she may not have achieved the pinnacle of stardom, Claire Trevor was that Hollywood rarity: a beautiful blonde who broke the mould and became an acclaimed character actress. She began her career at Fox in the 1930s, and like Marilyn after her, was frustrated by Darryl F. Zanuck’s indifference to her talent. She fared better at other studios, and played her first great role in John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939.) She went on to star in Farewell My Lovely (1944), and would win an Oscar for her outstanding performance in Key Largo (1948.)

By the 1950s, Claire was still working steadily in film, stage and television, and had found lasting happiness in her third marriage, to producer Milton H. Bren. As author Derek Sculthorpe reveals in his new biography, Claire Trevor: Queen of Film Noir, she was aware of the pressures faced by younger stars.

“At the same time, she talked more frequently about retirement. ‘What’s all this about, anyway?’ she asked. ‘The fame is nonsense – I’ve found that out – and I’ve been to all the parties I want to go to and had the social chi-chi. I can’t take it anymore.’ She expressed concern over some young actresses such as Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor and the physical and emotional effects the filmmaking business was having on them. She wondered why Monroe became ill whenever she made a film. ‘Is it exhausted nerves or a bronchial condition?'”

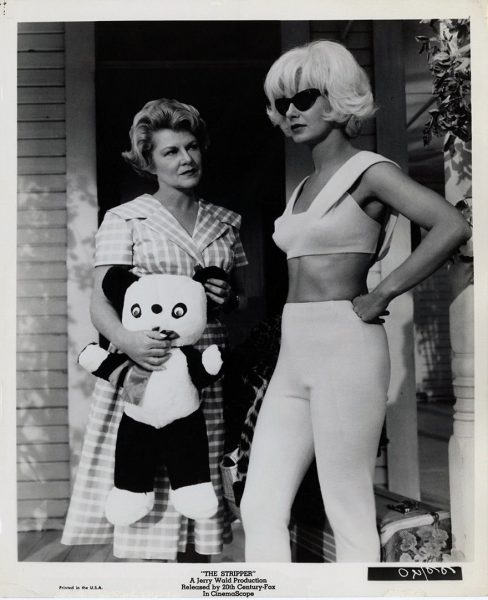

In 1963, Claire played Richard Beymer’s mother in The Stripper, adapted from William Inge’s play, A Loss of Roses. As Sculthorpe points out, the script had originally been earmarked for Marilyn in 1961, under the title Celebration. Costume designer Travilla had drawn up sketches for Marilyn’s character before she ultimately declined, committing instead to Something’s Got to Give.

“Joanne Woodward is a marvellous actress who did well wearing a platinum blonde wig looking for all the world like Marilyn Monroe. It was no surprise that the part was intended for Marilyn Monroe, which would have put the film in a different league. Monroe would have been a natural to convey the little girl lost at the heart of the piece, but died a short time before filming began. The male lead was offered to Pat Boone, who turned it down on moral grounds. Warren Beatty was also offered the role and he too declined. The part of the mother was offered first to Jo Van Fleet, who turned it down, after which it was given to Trevor.”

In Charles Casillo’s new biography, Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon – due out this month – he claims that Marilyn’s alleged rivalry with Elizabeth Taylor was a myth, as Closer reports. His source isn’t named here but hopefully the book will tell us more, as it’s a nice story. (And you can read my tribute to Marilyn and Elizabeth here.)

“They were two of the biggest female sex symbols of the 50s and early 60s, but Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor didn’t consider each other competitors. ‘In many ways [they] were pitted against each other by the press,’ Charles Casillo writes. ‘In reality, they barely knew each other, and the two had no animosity toward each other.’

Quite the opposite! Casillo writes of an incident in 1962, when 20th Century Fox was bleeding money on Liz’s over-budgeted extravaganza Cleopatra. The studio simultaneously fired Marilyn for alleged absences from the set of her never-completed final film, the aptly titled Something’s Got to Give.

Marilyn felt she was being sacrificed so Fox could save on her salary and spend it on finishing the bloated Egyptian epic. Two decades later, Liz revealed to a friend that she had reached out to Marilyn to offer her support during this difficult period.

‘Liz told Marilyn she was willing to publicly demonstrate her solidarity,’ Casillo says, offering to quit Cleopatra unless Marilyn was rehired. ‘Marilyn was very moved by Liz’s kindness toward her, but she didn’t want to make matters worse for either of them,’ so she declined the generous offer.

Instead, Liz gave Marilyn an invaluable piece of advice. ‘No matter what they write about me, Marilyn, I never deny it,’ Casillo quotes Liz as saying. ‘I never confirm it. I just keep smiling and walking forward. You do the same.’ Tragically, Marilyn didn’t live long enough to put those words into action.”

Last December, it was reported (here) that Disney had bought Twentieth Century Fox’s assets from its most recent owner, Rupert Murdoch. And on July 27, as Variety reports, the Fox-Disney merger went ahead with a $71.3 billion buyout. Marilyn’s films for her home studio will be included in the purchase. As many commentators wonder what this will mean for the venerable Fox brand, the Hollywood Reporter looks back on its colourful past with a series of articles including the fraught relationship between longtime studio head Darryl F. Zanuck and the biggest star of all – Marilyn – during 1951-62, a period described as the ‘Monroe Years’ (preceded by ‘Eve’s Gold Rush’ in 1950, a reference to the Oscar-laden All About Eve in which Marilyn had a small part.) Firstly, film historian Leonard Maltin offers a eulogy for Fox, and the personalities who made it great.

“Zanuck always had someone waiting in reserve in case one of his stars became uncooperative. Betty Grable was hired as a threat to musical star Alice Faye and soon surpassed her as Fox’s premier attraction (and No. 1 pinup) of the 1940s. Faye grew tired of Zanuck’s belittling behavior and walked off the lot one day without saying goodbye. (Zanuck wouldn’t have survived in the #MeToo or Time’s Up era. He was notorious for taking advantage of starlets.)

Zanuck reigned until 1956, when he resigned from Fox and moved to France to become an independent producer. In the fractious years that followed, the studio wooed him back for projects more than once, even allowing him to cast his mistresses (Bella Darvi, Juliette Greco, et. al) in leading roles. But while movie attendance soared during the years following World War II, it sank nearly as quickly with the introduction of television. Fox’s response was to unveil a widescreen process called CinemaScope and its aural equivalent, stereophonic sound. Films like the biblical epic The Robe drew people back to theaters. So did Fox’s newest star, blonde bombshell Marilyn Monroe.

It was believed the wildly expensive epic Cleopatra — which paid Elizabeth Taylor an eye-popping $1 million salary — nearly bankrupted 20th Century Fox, but president Spyros Skouras already was selling off the company’s valuable backlot (now known as Century City) before the movie’s budget ballooned to $44 million. Facts aside, Cleopatra became a scapegoat for all of the studio’s ills.

In a final coup, Darryl F. Zanuck returned to Fox in the early 1960s and named his son, Richard Zanuck, president … Then, in 1970, Zanuck Sr. fired his son and sparked an Oedipal family feud that sucked in Zanuck’s ex-wife — Richard’s mother, a major shareholder — and ended with the elder Zanuck being pushed out of the studio he co-founded. Repeated changes of regime and ownership in the ensuing years took their toll on the company that had once put its distinctive imprint on such classics as Laura, Miracle on 34th Street, Twelve O’Clock High and All About Eve.”

In another article, ‘Life in the Foxhole‘, Mitzi Gaynor describes the working atmosphere at Fox as ‘like a family’, while Don Murray recalls his movie debut at the studio, and his mercurial leading lady…

“Zanuck loathes Marilyn Monroe (‘He thought I was a freak,’ Monroe once said) and nearly tears up her first contract after her nude Playboy cover comes out. But by 1953, Monroe has three of the studio’s biggest hits — Niagara, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire — and renegotiates a new contract paying $100,000 a picture and giving her creative approval. Her first film under the new deal is 1956’s Bus Stop, co-starring Don Murray. ‘I’d never done a feature before,’ says the actor, now 88, ‘so I didn’t know what to expect. From what others on the set told me, Marilyn was on her best behavior. She’d just been to the Actors Studio, and she really wanted to concentrate on her acting. But even so, she was late every day. She’d get to the studio on time, but then she’d spend hours dawdling in her trailer, getting the nerve up to act. She was trying hard — she would sometimes do 30 takes in a scene — but she was very anxious about her acting. She would actually break out in a rash before the cameras would start filming. The cameras gave her a rash.'”

Finally, you can read Marilyn’s take on Fox, and Zanuck – as told to biographer Maurice Zolotow – here.

Marilyn’s first screen role, in Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! is featured in a list of movie stars who got their start as bit players and extras. Filmed in March 1947 – six months into Marilyn’s contract with Twentieth Century Fox – the film would not be released for another year. As ‘Betty’, Marilyn can be seen briefly in one scene. Leaving a church service, she says ‘Hi, Rad!’ to leading lady June Haver. Marilyn’s only other scene, where she and fellow starlet Colleen Townsend row a boat across a lake and chat with some local boys, was cut – although several stills from the production have survived.

Marilyn would play a slightly more substantial role in Dangerous Years before being dropped by Fox in July. Despite her minimal presence, Marilyn also posed for a series of ‘bathing beauty’ shots to promote the movie. More than half of her screen credits were made before she reached star status (not to mention a couple of other films which used her image without active participation), and while it has been rumored that she was also an anonymous ‘extra’ in several other movies, this remains unconfirmed.

Alongside A Ticket to Tomahawk (1950), Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! is the only one of her early films made in Technicolor, and a surprisingly enjoyable slice of rural Americana, with a young Natalie Wood, plus stellar character actors Walter Brennan and Anne Revere among the cast. Lon McCallister, who also appeared in Marilyn’s boating scene, later joined her during the Love Happy promotional tour.

The unusual title, referring to slang used by farm-workers to drive mules left and right, was later renamed Summer Lightning. But in the 1989 film, Driving Miss Daisy, the film’s original title can be seen on a cinema marquee.