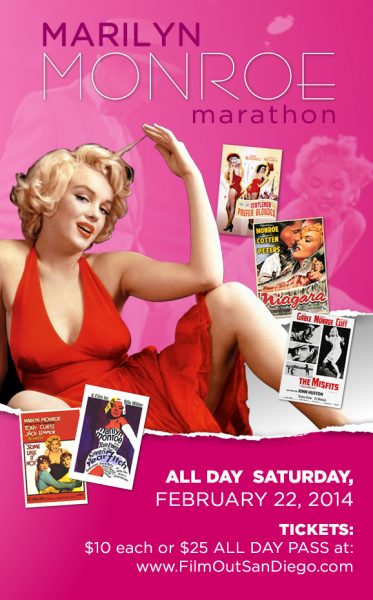

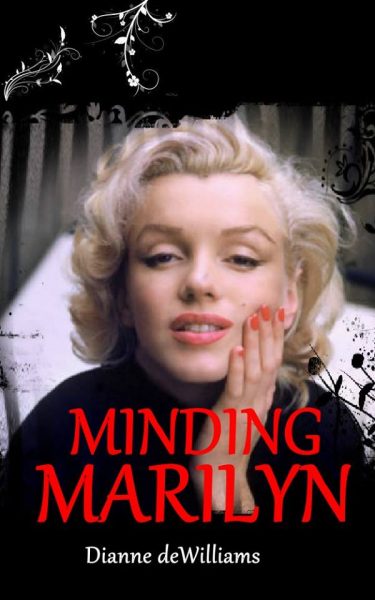

Minding Marilyn is a short novel by Dianne DeWilliams, published via Amazon Kindle in November 2013. It is written from the perspective of Marveen, a widow who is moving from New York to a retirement home in California, to spend more time with her two grand-daughters. When she shows them a photograph of herself as a beautiful young woman in a nightclub, alongside Marilyn Monroe, they demand to know more.

Back in 1952, Marveen was hired as a maid to Monroe, then on the brink of stardom. While in reality there was no ‘Marveen’, Marilyn did employ a maid, Lena Pepitone, who later published a ghost-written memoir. Although Marilyn Monroe Confidential offered some insight into the star’s daily life, it was highly sensationalised. Her Los Angeles housekeeper, Eunice Murray, wrote a more creditable book, Marilyn’s Last Months – but she is more often remembered as the woman who discovered Marilyn’s dead body.

Hazel Washington, Marilyn’s studio maid, was also said to have written a manuscript about her memories of Marilyn, but it was never published; while her cook, Hattie Stevenson, was planning to move from New York to Monroe’s Los Angeles home before the actress died. Another maid, Florence Thomas, attended her funeral.

Like Marveen, these lesser-known figures in Marilyn’s life were African-American. As well as a re-imagining of Marilyn’s private world, Minding Marilyn explores what it was like to be a black woman in the USA during the 1950s and ‘60s, when endemic racism was being challenged by the growing Civil Rights movement.

Marveen’s story is told alternately through letters written to her mother during her years with Marilyn, and a contemporary narrative detailing her efforts to commit her memories to print. DeWilliams has clearly done her research; and while her tale is fictional, the factual background is mostly accurate.

DeWilliams also inputs minor details about Marilyn’s life – for example, her love of Judy Garland’s song, ‘Who Cares?’ These simple touches help to create a rounded and sympathetic picture of Monroe’s personality.

It is well-known that Marilyn was ahead of her time in her progressive attitude towards racial equality. In 1954, she helped the legendary jazz singer, Ella Fitzgerald, to secure a residency at the Mocambo Club by promising to attend her show every night. She was also friendly with actress Dorothy Dandridge (dubbed ‘the black Monroe’), who features prominently in Minding Marilyn.

DeWilliams also includes another screen goddess, Ava Gardner, in the storyline. In reality, Marilyn and Ava didn’t know each other well. But they both came from modest backgrounds, and both were close to Frank Sinatra. Ava’s wild, earthy character makes an exciting contrast to the ambitious, but fragile Marilyn.

Gardner, the daughter of a North Carolina sharecropper, grew up among black people. Despite the colour bar that existed in Hollywood, she mixed freely with all races. Her maid, Mearene Jordan, was also her best friend. Living With Miss G, Jordan’s personal account of their many adventures spanning almost fifty years, was published in 2012, and provides a real-life parallel to Minding Marilyn.

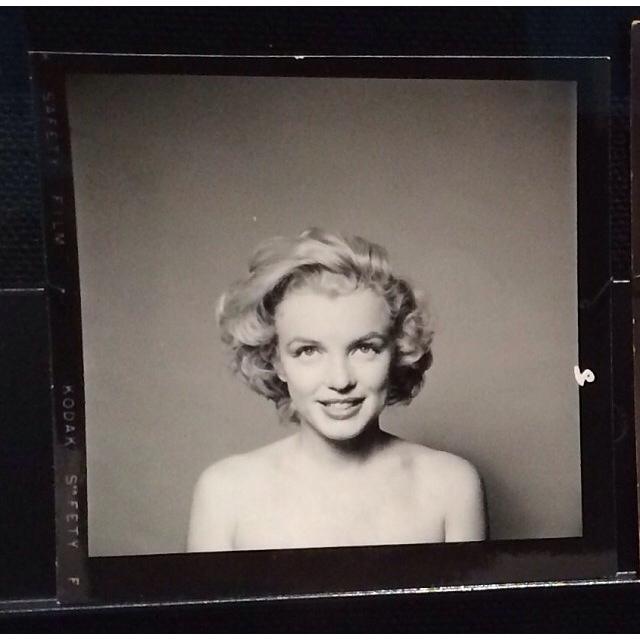

While being a maid might be seen as a ‘subservient’ position, Marilyn was both thoughtful and generous towards those who worked for her, at home and on film sets. DeWilliams makes an interesting point that black audiences related more to Marilyn than other white stars, because she was ‘no stranger to pain’ – whether through suffering the impact of childhood trauma, or experiencing the pressures of fame. This observation about her cross-cultural appeal is echoed in W.J. Weatherby’s 1976 book, Conversations With Marilyn.

Sadly, Monroe seldom experienced the loving support of a group of female friends depicted by DeWilliams in Minding Marilyn. Although she was not particularly religious, in one scene she is welcomed into a Pentecostal church. DeWilliams seems to be suggesting that these are alternate paths which might have led Marilyn towards a lasting happiness that eluded her in reality.

DeWilliams evokes the deep shock felt by Marilyn and those around her when, in 1961, she was committed to a psychiatric ward against her will. Famously, her devoted ex-husband, Joe DiMaggio, came to her rescue. But DeWilliams implies that in times of crisis, the ‘little people’ who served Marilyn were just as valuable to her as the major players.

Minding Marilyn imagines a different response to Marilyn’s tragic death, in which the voice of Marveen is finally heard, setting the record straight. As a piece of writing, Minding Marilyn is not perfect – the paragraphs can be short and choppy, the sentences a little breathless – but the warm-heartedness of DeWilliams’ tale more than compensates for these minor shortcomings.

Although fictional, Minding Marilyn offers something that many of the biographies published over the years cannot – a sweet, charming tribute from a fan, and a testament to the sincere affection in which she is held by so many of us.

Reviewed by Tara Hanks, author of The Mmm Girl

Also available on Amazon.com

Book trailer for Minding Marilyn

Facebook page for Minding Marilyn

Read more about Marilyn’s employees