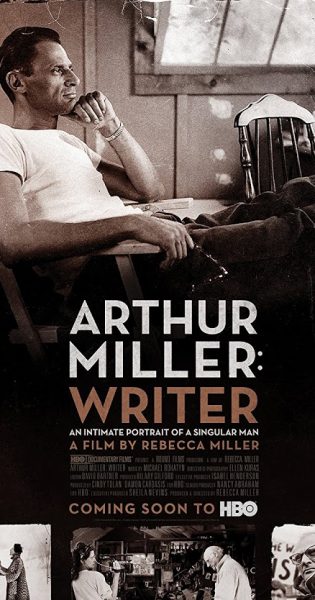

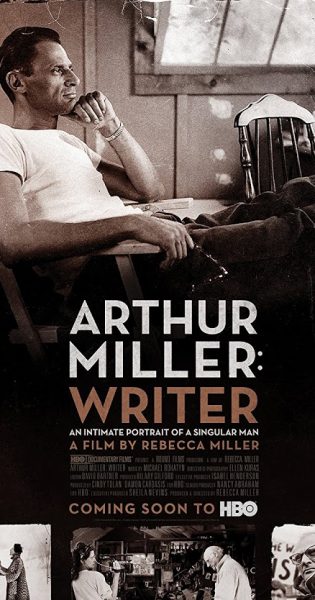

You can read my review of Arthur Miller – Writer, the intimate 2017 documentary made by his daughter Rebecca Miller, here.

Marilyn Monroe 1926-1962

You can read my review of Arthur Miller – Writer, the intimate 2017 documentary made by his daughter Rebecca Miller, here.

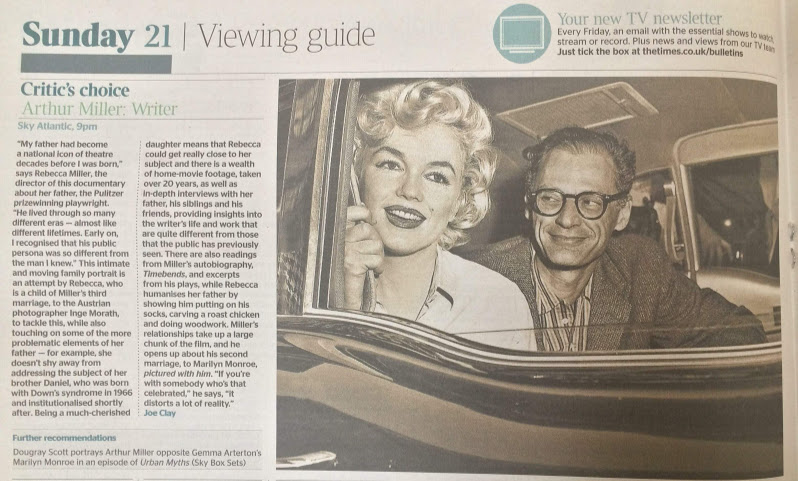

‘When you’re with someone who’s that celebrated, it distorts a lot of reality,’ Arthur Miller said of his marriage to Marilyn. Rebecca Miller’s documentary about her father, Arthur Miller: Writer, will have its UK premiere on Sky Atlantic tomorrow (Sunday, October 21) at 9 pm, as reported in The Times.

Thanks to Fraser Penney

Carl Rollyson, author of Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress, has set out his thoughts on Arthur Miller: Writer, the new documentary made by Miller’s daughter Rebecca, now on HBO in the US.

“It is a remarkable revelation of the man, but it is also a very limited view. How could it not be? It is his daughter’s film , and she could not, for example, bring herself to interview him about his institutionalized Down’s syndrome son. The film is really a memoir, and not a biography.

But I am going to concentrate on the treatment of Marilyn Monroe. For the most part, she is treated as rather pitiful, with Miller spending his time propping her up. He wrote very little while married to her but does not mention the countless hours locked away in a room trying to write. More importantly, he gives a very distorted view of what happened during the shooting of The Misfits. He says she doubted she could perform in a serious role. This is a staggering lie, or an example of self-delusion. Monroe was upset about the script and was shut out from the Miller-Huston deliberations about how to fix it. She wasn’t happy that her husband was treating her as a myth, not a real person. If he was going to give her lines that she actually had spoken, then he was obligated to give the full context in which such lines were spoken.

The most telling moment occurs earlier when Miller mentions Elia Kazan as telling him what a great play Death of a Salesman was. Kazan may have been the first one to say so to Miller. Miller trusted Kazan’s judgment and his sincerity. But when it comes to The Misfits, Miller does not mention the letter [Elia] Kazan sent him detailing the faults with the character of Roslyn that Monroe had to play. And those faults were exactly the ones Monroe had identified.

Another telling moment in the film is when Tony Kushner analyzes After the Fall and says Miller was afraid of Monroe. Just so, she had a much more capacious sensibility than he did, and he did not know how to respond to her. The same is true with Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. When she died, Hughes said, ‘It was her or me.’ In both cases, these men simply could not come up to the level of their wives, and afterwards suggested that was because the wives were doomed. And that is the impression Miller conveys in his daughter’s film.”

Sophie Gilbert has praised Arthur Miller: Writer as a ‘loving portrait‘ in her review for The Atlantic. Rebecca Miller’s new documentary can now be viewed by HBO subscribers in the US (I will update this blog when it becomes more widely available.)

“Arthur Miller: Writer is a family portrait defined by intimacy with its subject, captured in footage the filmmaker first started shooting in her 20s. The movie’s at its most intriguing when it’s parsing the strangeness of being closely related to someone so celebrated, who put so much of his life in his work. Rebecca’s sister, Jane, recalls how, conversing with her father when she was younger, ‘There were times when he was only interested in something because he could use it.’

It’s a surprise, though, how warm and goofy Miller is in scenes with his daughter, as she captures him working on carpentry projects in his studio in Connecticut or reminiscing in his kitchen. Rebecca Miller, when the camera turns to her, watches him intently, with palpable affection.

Monroe, Miller’s second wife, is a substantial part of the film, although not an overwhelming one. It’s almost as though Rebecca Miller feels reluctant to probe too deeply into her father’s romantic life, even though he himself laid much of it bare in the 1964 play After the Fall. (‘The best work that anybody ever writes is the work that is on the verge of embarrassing him,’ Miller says in one interview.) When Miller and Monroe were first introduced in 1951 he recalled telling her that she was the saddest girl he’d ever met—a line he later put into The Misfits, a film he wrote for her to star in. Their marriage captivated America, given the unlikely union of a brilliant intellect and an incandescent movie star.

But Miller seemed to comprehend the pain within Monroe, who forged a bond with her new father-in-law that lasted until her death. ‘She couldn’t really gain for herself the confidence she had to have to do this,’ Miller tells his daughter. Then he sits, silently, for what feels like minutes, his face distorted with pain. ‘Terrible,’ he says. ‘Well.'”

Arthur Miller: Writer, the new documentary from daughter Rebecca Miller, has its US television premiere on pay-per-view channel HBO tonight. Over at The Ringer, Lindsay Zoladz has penned a rather wide-ranging article about Marilyn and Arthur, including hints of what’s in the documentary.

“When Arthur Miller met Marilyn Monroe, she was crying. Or at least that’s the story he always told her, the one she repeats in footage used in the new documentary Arthur Miller: Writer: ‘As he describes it, I was crying when he met me.’ As he describes it.

Comprising home movies and interviews Rebecca shot of her father in his later years, Arthur Miller: Writer has a homey, scrapbook intimacy … Rebecca was born in 1962, just weeks after Monroe died. Imagine grilling your elderly father, on camera, on what it was like to have been with Marilyn Monroe.

The portrait of Monroe that emerges from Arthur Miller: Writer, then, is inherently lopsided and not nearly as intimate as the one we get of Miller himself. One of the hardest parts of putting together the film, Rebecca admits, was finding ways to diminish Monroe’s presence, to prevent her from completely overtaking her father’s story … Monroe always seems to be doing that—inconveniencing narratives. It’s the most potent power she’s retained after death.

Monroe has, throughout the years, been a sticking point for feminists; the many contradictions of her story do not fit cleanly into the doctrines of any of its waves. Perhaps for the best, she maps particularly awkwardly onto this moment of pop-cultural ’empowerment feminism’ … And yet gender stereotypes are exactly what imprisoned Monroe, and what her star persona was crafted to reinforce.

‘I just thought it would be a terrific gift for her,’ he says in Arthur Miller: Writer, ‘because she’d never had a part in which she was supposed to be taken seriously. And she really wanted to do that.’

Arthur Miller: Writer is, among other things, a fresh reason to mourn the fact that Marilyn Monroe never got to be old and wise like her last husband … But maybe, at least for a fleeting moment, Miller took her seriously. In Rebecca Miller’s interviews, filmed at his kitchen table in Connecticut near the end of his life, the playwright seemed to retain a real compassion for his second wife.

‘She was witty,’ Miller says, gazing wistfully from his kitchen table in Connecticut. ‘She was making fun of the situation as she was playing it. That was the difference. People thought they could imitate her by being cute. But she was being cute and making fun of being cute at the same time. There was another dimension, which is very difficult to do.'”

The author and filmmaker Rebecca Miller has spoken with Maureen Dowd for the New York Times about Arthur Miller: Writer, a documentary about her father which makes its US television debut on HBO on March 19. Unlike Arthur’s older children, Robert and Jane, Rebecca never knew Marilyn personally, but her marriage to Arthur is important to the film.

“She felt there was ‘a huge gap’ between the cozy storyteller she saw at home, who enjoyed woodworking, and the cool intellectual she saw in interviews. ‘He had a remoteness in interviews, because he was a shy person and he was very protective of himself, understandably at that point,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘It was a feeling like, his warmth and his humor would never really come through.’

Ms. Miller found that portraying her father’s passionate romance with Monroe was ‘very tricky.’

‘I felt sometimes almost that I shouldn’t be in the room, I shouldn’t know all this stuff,’ she says. ‘There was this one moment that we created a scene with still pictures where he seems to be looking at her and she’s standing there and he says, You’re the saddest girl I’ve ever met. It was weird, but that was also the moment where I sort of transformed from a daughter into a filmmaker. And I also ended up sort of seeing how she was just a person, you know? Because there’s so much smoke around her. She would even tend to take up huge amounts of space in the film. I was constantly trying to cut it down again, because she has so much light coming out of her. So much charisma. I just said, ‘O.K., how can we penetrate the mystery a little bit of this woman and this man and in the end find some clarity?’

She puts one of her father’s searing love letters to Marilyn up on screen, reading: ‘So be my love as you surely are. I think I shall be less furiously jealous when we have made a life together. It is just that I believe that I should really die if I ever lost you. It is as though we were born the same morning when no other life existed on this earth. Love, Art.’

The romance that began with such passion devoured itself. ‘He was really, really worn down,’ his daughter says. ‘He hadn’t gotten any work done for a long time, and this was a man who completely identified himself as a writer. And that had been put away, barring The Misfits, which was itself excruciating. But I think she had had it, too. They were not matched. They tried and they just bungled it.’

“She was the rose and he was definitely the gardener. But he’s more of a rose and he needed a gardener. People can only play the other part for so long.’

‘You can’t really save someone,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘You have to acknowledge that you’re you and I’m me, and your powers don’t extend to being a savior. My impression is for whatever reason, I don’t know exactly, but she saw death was luring her for a long, long time, and I think that had to be her end point.’

The director originally put in Ms. Monroe’s pregnancy during Some Like It Hot, and her subsequent miscarriage, but then cut it. ‘We had a version where we see her going into the hospital,’ she says, ‘but it’s that line of what’s gossip and what’s getting to the meat of the matter?’

I tell Ms. Miller that I have always had a dim view of her father’s treatment of Marilyn: because of his play After the Fall, about a Jewish intellectual in New York married to a needy show business idol who commits suicide, which he at first denied was even about Marilyn; and also because he crushed her during their marriage by leaving an open journal for her to find, with an entry about how she had disappointed him and embarrassed him in front of his brainy peers.

‘Maybe he did it unconsciously,’ Ms. Miller says about her father leaving out his journal. ‘But you know what? The unconscious, you never know.’

When she was still single, Inge Morath happened to be working on the set of The Misfits for her photo agency, Magnum, and took some haunting pictures of the luminous blonde with the darkness inside.

‘My mother was always very sweet about Marilyn,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘She really liked her. Someone asked her how the marriage between Marilyn and my father was and my mom was like: Oh, very happy. They seemed very happy. Because she wasn’t paying attention.’

If Ms. Miller had to summon her nerve to deal with the lusty and sorrowful side of her father that bubbled up with Marilyn, she also had to summon her nerve to deal with the most disturbing part of the documentary: the institutionalization of her younger brother, Daniel, who was born in 1966 with Down syndrome.

A 2007 Vanity Fair article suggested that Daniel had basically been abandoned in an ‘understaffed and overcrowded’ facility in Connecticut, with his father rarely visiting.

‘I think the Vanity Fair article was written in a spirit of malice,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘They made it seem like he never saw him, which wasn’t true. He did see him. It’s just that it wasn’t, perhaps wasn’t, enough. But you also have to put things in a little bit of historic perspective. There were other families who put their Down syndrome children in institutions. I don’t know. It’s a mystery. And really, finally, in the film, I was ultimately honest with my own limitations and where my knowledge ends. I don’t know exactly what transpired between those people because they never told me. All I know is what my relationship is with my brother, which is great.'”

Arthur Miller: Writer, a new documentary made by his daughter Rebecca and covering his extraordinary life and career (and Marilyn, of course), will have its US television premiere on pay-per-view channel HBO from March 19, reports Broadway World.

Arthur Miller: Writer, a new documentary helmed by his daughter, the author and filmmaker Rebecca Miller, will have its premiere as part of this year’s New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, Deadline reports. (The festival runs from September 28 – October 15, and as previously reported here, Marilyn’s 1954 Western, River of No Return, will also be screened as part of a Robert Mitchum centennial retrospective.)

“Rebecca Miller’s film is a portrait of her father, his times and insights, built around impromptu interviews shot over many years in the family home. This celebration of the great American playwright is quite different from what the public has ever seen. It is a close consideration of a singular life shadowed by the tragedies of the Red Scare and the death of Marilyn Monroe; a bracing look at success and failure in the public eye; an honest accounting of human frailty; a tribute to one artist by another. Arthur Miller: Writer invites you to see how one of America’s sharpest social commentators formed his ideologies, how his life reflected his work, and, even in some small part, shaped the culture of our country in the twentieth century. An HBO Documentary Films release.”

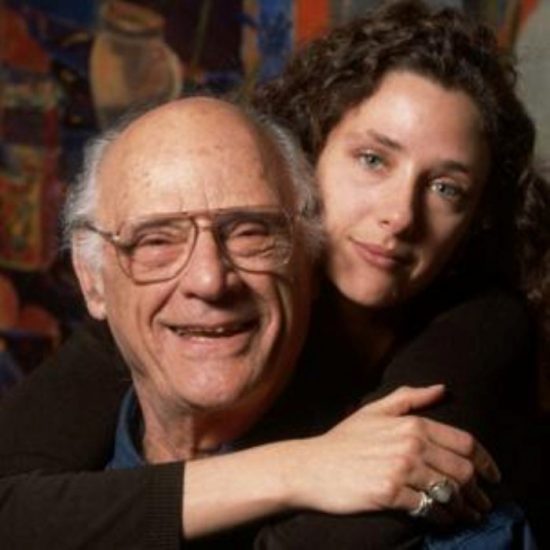

Rebecca Miller, daughter of Arthur, is a writer, director, and actress. She was born a month after Marilyn’s death, to Arthur and his third wife, Inge Morath.

Rebecca spoke to the New York Post recently about the way some of her father’s plays are overshadowed by the memory of Marilyn.

“As for After the Fall and Finishing the Picture — Miller’s two plays about his second wife, Marilyn Monroe — Rebecca remains wary.

‘Anything that’s got the shadow of Marilyn in it — even something that has just a slight taste of her — gets overshadowed by her,’ she says.

Finishing the Picture, Miller’s final play, is about the making of Monroe’s last movie, The Misfits, for which he wrote the screenplay. There has been just one production, at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre in 2004.

It’s a fascinating story with some terrific parts for larger-than-life stage actors. ‘But I’m holding back on it,’ says Rebecca. ‘I’m guarding it. Sometimes it’s good to hold.’

She calls After the Fall, which Miller wrote in 1963, shortly after Monroe died, ‘a wonderful play that unfortunately in his time got completely read as an autobiographical work about her. You can’t pretend she’s not there, but at the same time it is about other things. There are meditations on the Holocaust and how we all have murder inside us.’

Rebecca says she’d like to see a production that ‘skews the play’ away from the Monroe character.

Which probably means a production with a major star in the male lead.

‘If the right person comes along, I’d certainly consider it,’ she says. ‘But nobody’s asking to do it.’

Now that’s a challenge a great actor — Kevin Spacey, perhaps? — should pick up.”

Actress Joan Copeland, 83, is the sister of Arthur Miller. Marilyn is photographed with Joan, above, at the 1957 opening of Noel Coward’s Conversation Piece.

Joan’s Show, a solo performance featuring reminiscences about her famous family and highlights from her long career, will be staged at the Acorn Theatre, 42nd St, New York, on August 15 (at 7 pm) and August 18 (at 2 pm.)

Copeland began her career on Broadway, and has appeared on television and in films including The Private Lives of Pippa Lee (2009), written and directed by her niece, Rebecca Miller.

In 1958, Joan appeared in The Goddess, a bleak melodrama believed to have been based on Marilyn’s life. Monroe had previously rejected another movie project by its author, Paddy Chayevsky.