Born in 1893 to Belarusian Jewish immigrants, Ben Hecht became a noted Chicago reporter and novelist before scoring his first Broadway hit with The Front Page (1928.) He later became one of Hollywood’s greatest (and most prolific) screenwriters. This month, two new biographies of Hecht will be published.

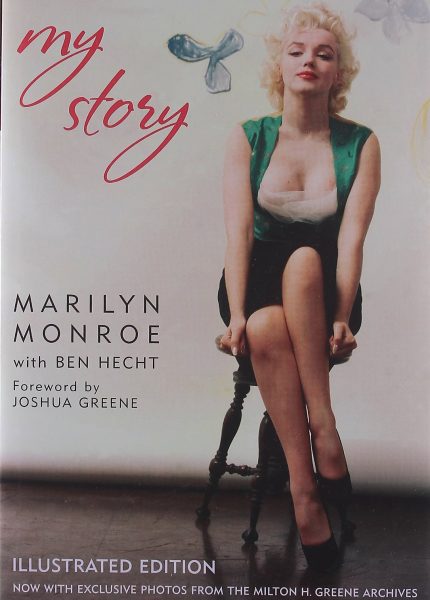

The first, Adina Hoffman’s Ben Hecht: Fighting Words, Moving Pictures, is part of a ‘Jewish Lives’ series from Yale University Press. In it, Hoffman explains how Hecht came to be the ghostwriter for Marilyn’s 1954 memoir, My Story. (Julian Gorbach’s The Notorious Ben Hecht will be published at the end of March.)

Although Hecht was not an observant Jew, he became involved with the Zionist group Irgun during World War II. After the war ended, he openly supported the Jewish insurgency in Palestine, and in a 1947 open letter, he praised underground violence against the British.

A year later, the Cinematograph Exhibitors’ Association announced a ban on all films connected to Hecht. Filmmakers became reluctant to work with Hecht and thus jeopardize the lucrative UK market, and he was forced to take salary cuts and adopt pseudonyms until the boycott was lifted in 1952.

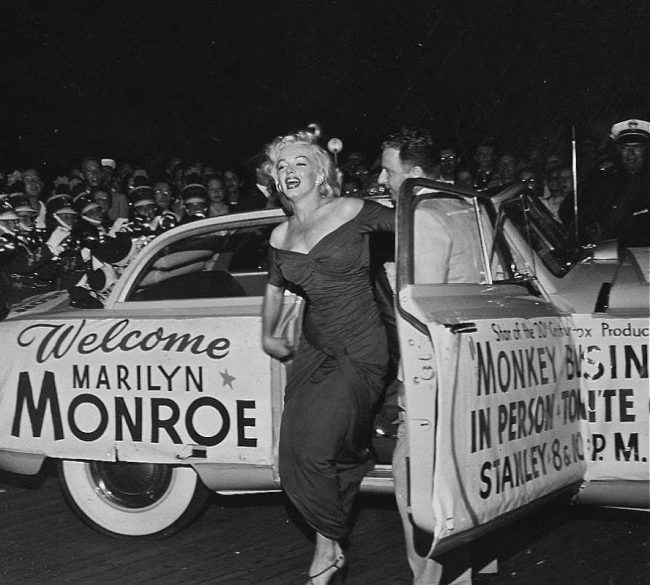

According to Hecht, Darryl F. Zanuck was “the only studio head who would hire me and use my name … [and he] got into a peck of trouble doing it.” As Adina Hoffman reveals in her book, Hecht worked with two longtime collaborators, writer Charles Lederer and director Howard Hawks, on a 1952 screwball comedy starring Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers and Marilyn Monroe. Originally titled Darling, I Am Growing Younger, it was later renamed Monkey Business.

In early 1954, Hecht spent five days in a San Francisco hotel interviewing Marilyn, whom he called ‘La Belle Bumps and Tears’. (His secretary Nanette Barber fondly recalled the sessions in a 2012 interview, posted here.) To Ken McCormick, the Doubleday editor who commissioned the project, he described the experience as “the longest series of log jams I’ve ever run into.” Hecht had back taxes to pay, and needed the money.

At first, he said, Marilyn was “100% clinging and co-operative”; but after her marriage to Joe DiMaggio, “the picture changed.” At DiMaggio’s behest, Marilyn’s lawyer demanded far tighter control. When the marriage collapsed months later, a devastated Marilyn refused to mention the divorce in the book.

Calling the situation “critical,” McCormick proposed “shift[ing] this all over into the third person and do[ing] a Ben Hecht biography of Marilyn Monroe … It seems to us that this would give you an elegant chance to write one hell of a book about Hollywood.” According to Hoffman, Hecht preferred to remain anonymous. Meanwhile, his shady agent Jacques Chambrun secretly sold the manuscript to a British tabloid. It was then serialised with neither Hecht’s nor Marilyn’s permission, landing the writer in legal trouble.

The book, My Story, wouldn’t be published until 1974, when both writer and subject were deceased. It was only in 2000 that Hecht was acknowledged publicly as the author. In a recent essay for Affidavit, Audrey Wollen wrote, “Hecht’s version of Monroe’s life set a cultural precedent for every future biography.” You can read more about its backstory here.