Anne Carson’s verse play, Norma Jeane Baker of Troy, baffled New York’s theatregoers in 2019. The script has now been published, though I must admit I was rather underwhelmed. But art critic Audrey Wollen, who wrote a perceptive essay last year about images of Marilyn reading, has contributed an intriguing analysis of the play in the February/March issue of Book Forum.

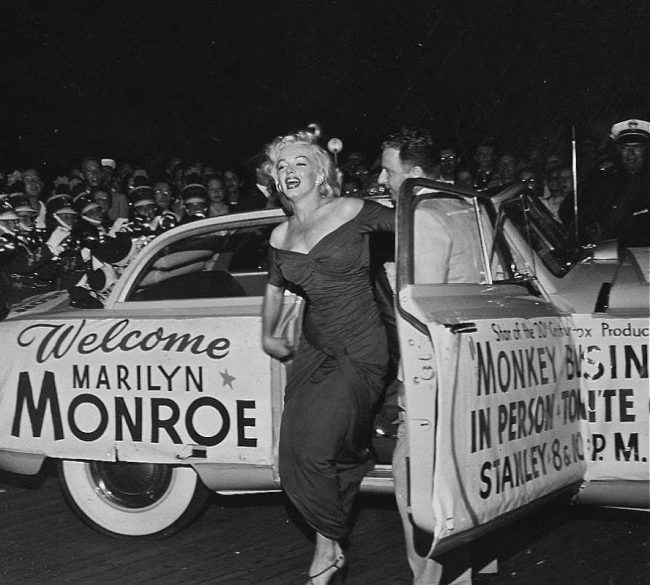

“As legends, the parallels between Marilyn and Helen are obvious. They are both superlative in their femininity, girl-ness at god level, with beauty that made them special and made them suffer. Marilyn never directly caused any international conflicts (despite that little JFK subplot), but she has still become a cautionary tale, although what exactly we are cautioned about is unclear. (Personal despair? Public sexuality? Tomato, tomato.) And while she eventually identified as a leftist, officially un-American, her image was often wedded to America’s wars. In fact, her entire career is owed to it: She was discovered as a model while working in a factory assembling drones during World War II, smiling wide next to heavy, morbid machinery. Her ‘bombshell’ moniker greased the association, her name slipping between sex, death, and nation. By the time she visited the American troops in Korea in 1954, a hundred thousand soldiers came out to express their desire and, by extension, their allegiance. Like Helen, she was what they were fighting for.

The play ends with language hardening its shell into event again. The kernel of the story that Carson wants to tell is sung early on: ‘Rape is the story of Helen, Persephone, Norma Jeane, Troy. War is the context and God is a boy. . . . Truth is, it’s a disaster to be a girl.’ At the story’s close, an earthquake hits Los Angeles, causing a tsunami to flood the entire city: ‘Aristotle thought earthquakes were caused by winds trapped in subterranean caves. We’re more scientific now, we know it’s just five guys fracking the fuck out of the world while it’s still legal.’ The light changes, ‘like morning at midnight,’ and our heroine leaves the hotel for the first time, sailing on a war boat through Hollywood’s sunken ruins. Like Euripides, Carson closes the curtains on the wide, open sea. Another fantasy floats to the surface, another absolution: Norma Jeane escapes, inheriting Helen’s endlessness. The clouds watch from above, in sisterhood.”