Among the many revelations to be found in the new Julien’s catalogue are a series of notes made by Marilyn on her work at the Actors Studio, where she once played Blanche DuBois in a scene from Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire.

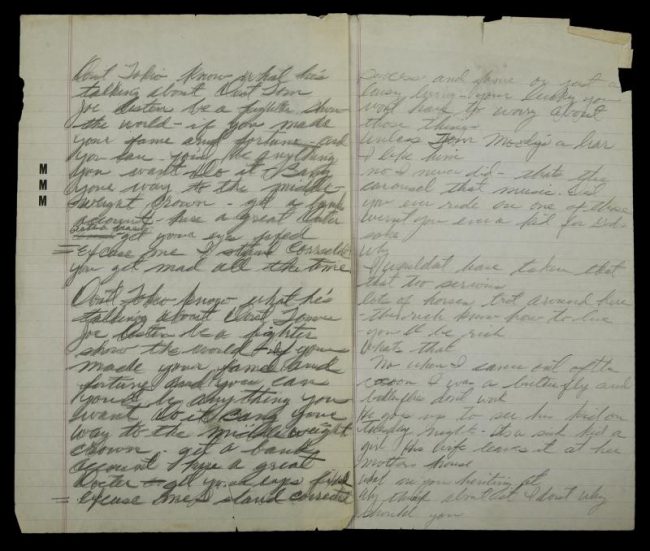

“A black board notebook with red spine containing lined notebook paper with notes in Monroe’s hand. A very large letter ‘M’ is drawn inside the front and back covers. There are multiple notes written in another hand on the first page of the book, but the next page contains notes in Monroe’s hand in pencil with ideas for a ‘Street Car Scene’ reading in part, ‘begin with ? (1st grade happening Mexican boy accuses me of hurting him – having to stay after school it was nite [sic] outside – have place – concern because of Stan K. accusations plus – getting dress for Mitch trying to look nice especially since what Stan K. has said.’ The note also suggests she hum ‘Whispering while you hover near me,’ which is a song standard found in her notebook of standards in the following lot, only the lyric is ‘Whispering while you cuddle near me.’ The front and back of the last page of the book contain notes from acting class, including ‘during exercise – lee said let the body hang’; ‘2 exercises at one time/ cold & Touch/ one might not be enough for what’s needed’; and ‘sense of oneself/ first thing a child (human being) is aware of (making a circle) touching ones foot knowing himself is separate from the rest of the world,’ among others.”

Marilyn also studied the role of Lorna Moon in Clifford Odets’ Golden Boy, writing her lines twice to memorise them.

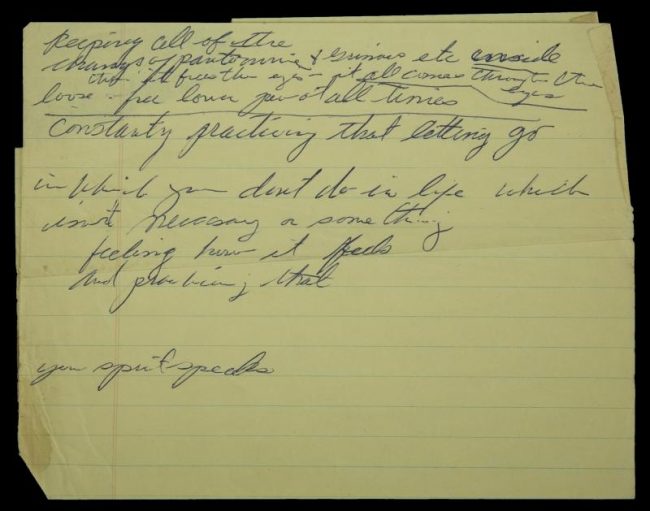

Also on offer is an undated note which reads in part, “keeping all of the changes of pantomime & grimaces etc inside, then it forces the eyes – it all comes through the eyes”; and “Constantly practicing that letting go/ in which you don’t do in life which isn’t necessary or something/ feeling how it feels and practicing that/your spirit speaks.”