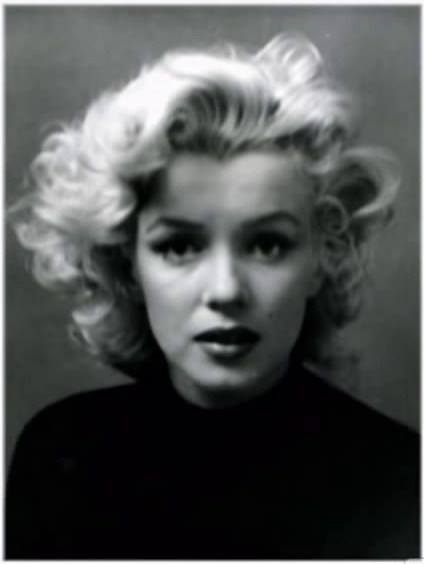

“That’s the trouble, a sex symbol becomes a thing. I just hate to be a thing.” – Marilyn Monroe, 1962

After recent news of a legal battle between ABG (Authentic Brands Group, the licensing arm of Marilyn’s estate) and a company known as Virtual Marilyn LLC, the Wall Street Journal reveals that ABG are planning to launch their own 3-D, digitised Marilyn. Crass hypocrisy or an exciting new venture? You decide…

“The iconic actress is getting digitally revived by Pulse Evolution, the company that brought to life Michael Jackson this past year at the Billboard Music Awards. They’ve signed a long-term deal with the rights holder to Monroe’s estate Authentic Brand Group(ABG) to develop a commercially viable digital replica of her for commercials, TV shows, films and even a live show.

The partnership was signed at the beginning of October and there’s already a four-year commercial deal in place that ABG CEO Jamie Salter says is with a Fortune 500 cosmetic company worth over $100 million dollars. The two companies plan to split profits 50/50 for revenue she generates through Pulse’s creation.

‘This is a digital asset that’s digitally distributal,’ says Pulse CEO Frank Patterson. ‘Popularly [they’re] being referred to as holograms because people don’t know how to talk about it. We’re talking about the digital likeness of humans. Digital humans are new to us as a society. There’s a lot of spaces where digital humans will become very useful.’

Patterson says these aren’t true holograms and that we’re years off from developing that technology. Instead, they’re a ‘3-D digital object.’

For Pulse and ABG, they’re proceeding with caution, while at the same time trying to monetize her with new technology. ‘There’s only one Marilyn Monroe in the world, and we’re going to be very careful with her,’ Salter says.

Still, while there may be just one Monroe, the possibilities of putting her into a live setting are much different than your typical real-life performer. ‘Unlike a typical show, Marilyn Monroe can be in more than one location at a time,’ Patterson says. ‘Why couldn’t we open a show in Vegas and Seoul at the same time?’

Pulse plans to hire a creative team of writers, directors, and costume designers to flesh out the live show Monroe would undertake. They’re already well underway in developing a show for Elvis Presley, who they secured a deal with in August.

‘We’re taking these assets and applying them to traditional business structures,’ Patterson says. ‘First having them appear in major venue installations – think of a casino appearance with a major, 52-week show commitment. Then rolling them out into touring presentations and special appearances, generating sponsorship and branded-content opportunities.’ He says that it would take about 18 months to roll out a show of this nature, including time to build Monroe’s digital persona. When asked about whether or not venues would be interested in something like that, the response was ‘overwhelmingly positive.’

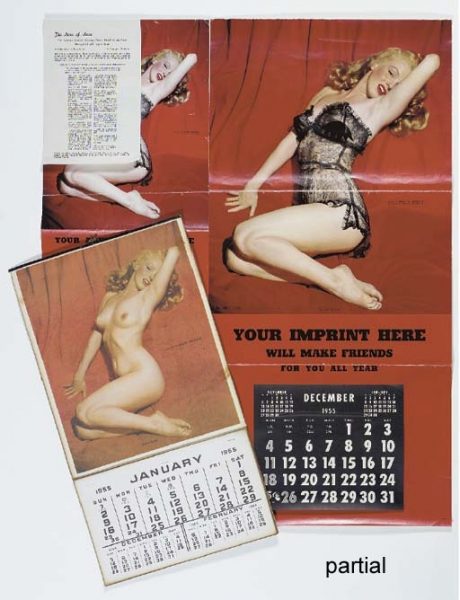

For ABG, the focus seems to be more about continuing using Monroe’s image for commercial purposes, as she did in a 2011 commercial spot where her likeness was used alongside Charlize Theron for a J’Adore Dior ad. ‘We’re sticking with the best companies in that [fashion] space,’ Salter says. ‘We’ll be very careful when Marilyn Monroe takes a job from a model standpoint. We’re treating her no different than if Brad Pitt or Lady Gaga was our client.'”