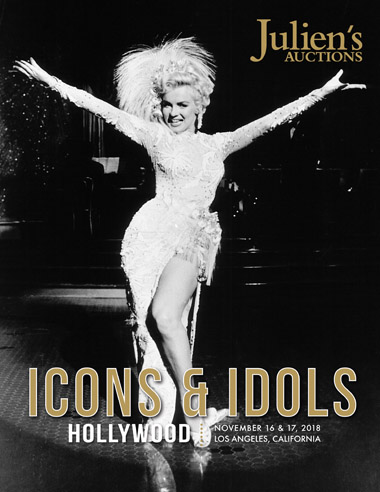

A wide range of Marilyn-related items, including her 1956 Thunderbird, will be up for grabs at Julien’s Icons & Idols auction on November 17. Another high-profile item is the white beaded Travilla gown worn by Marilyn when she sang ‘After You Get What You Want, You Don’t Want It’ in There’s No Business Like Show Business, purchased at Christie’s in 1995; as yet it’s unclear whether this is the same dress listed at Julien’s in 2016.

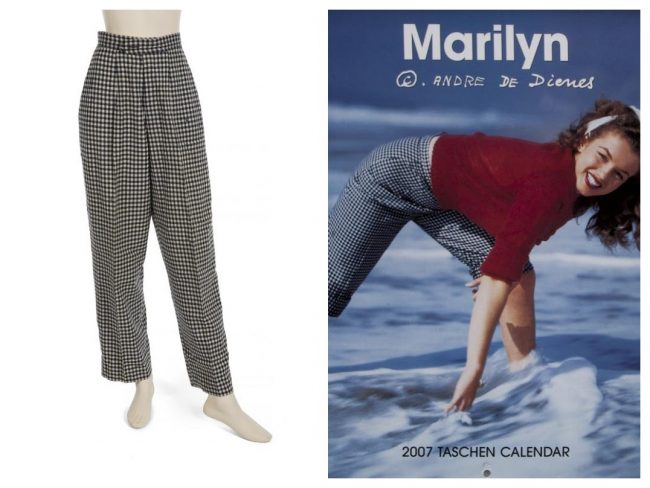

Marilyn owned several pairs of checked trousers, wearing them repeatedly throughout her career. This pair, seen in one of her earliest modelling shoots, was purchased from Sak’s Fifth Avenue.

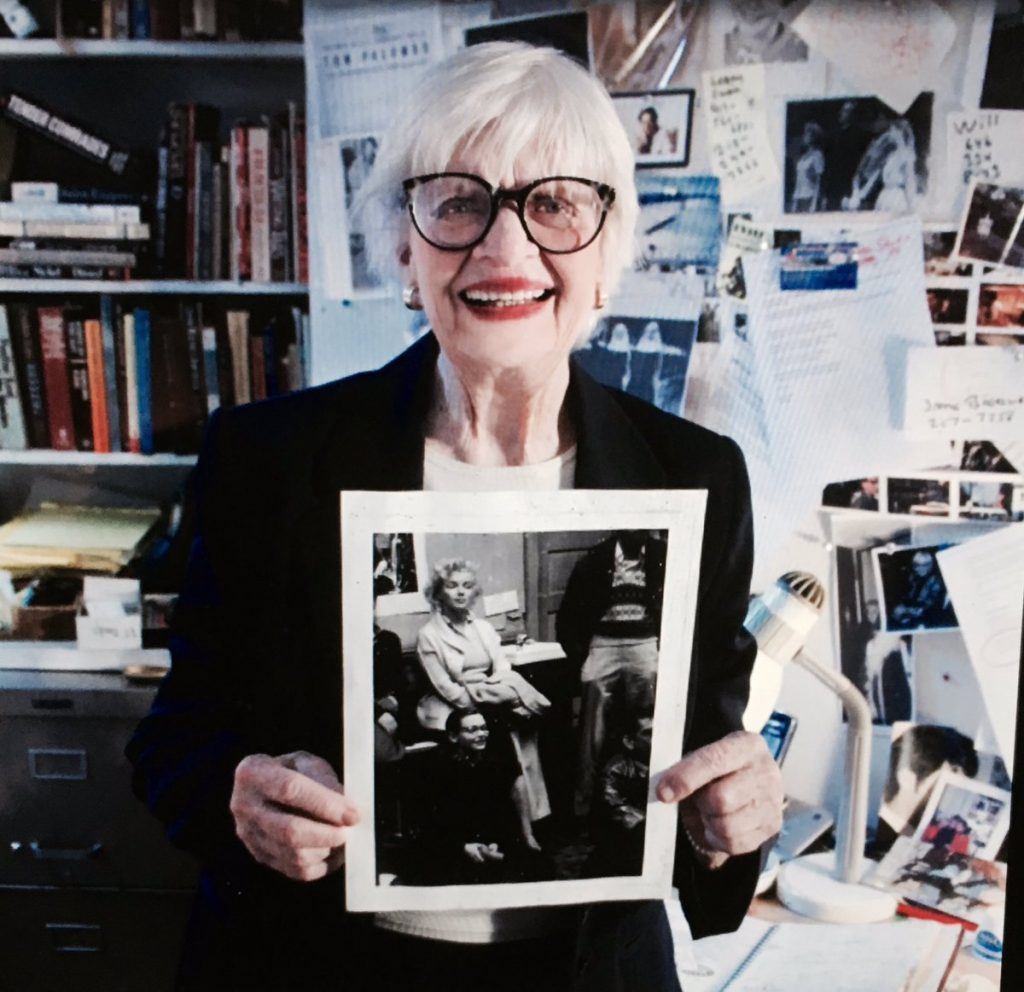

A number of photos owned by Marilyn herself are also on offer, including this picture with US troops, taken on the set of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes; a set of publicity photos for Love Nest; a photo of Joe DiMaggio in his New York Yankees uniform; and Roy Schatt‘s 1955 photo of Marilyn and Susan Strasberg at the Actors Studio.

A postcard from the Table Rock House in Niagara Falls was signed by Marilyn and her Niagara co-stars, Jean Peters and Casey Adams, in 1952.

This publicity shot from River of No Return is inscribed, ‘To Alan, alas Alfred! It’s a pleasure to work with you – love & kisses Marilyn Monroe.’

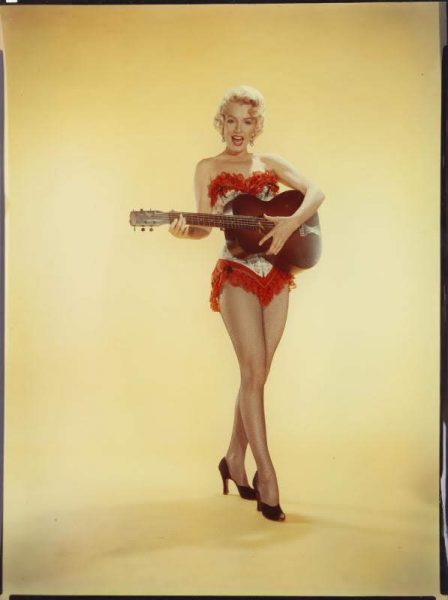

A set of bloomers worn by Marilyn in River of No Return (as seen in this rare transparency) is going up for bids.

Among the mementoes from Marilyn’s 1954 trip to Japan and Korea are two fans and an army sewing kit.

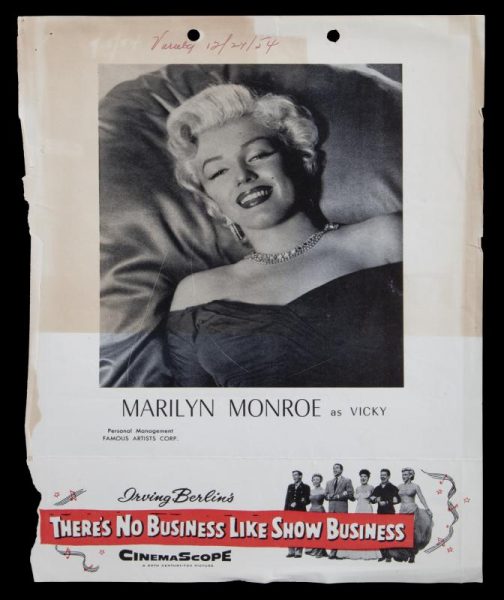

Also among Marilyn’s personal property is this ad for There’s No Business Like Show Business, torn from the December 24, 1954 issue of Variety.

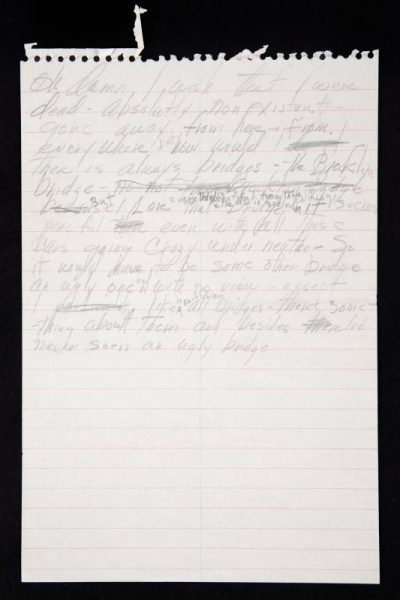

Marilyn’s hand-written poem inspired by Brooklyn Bridge is also on sale.

Among Marilyn’s assorted correspondence is a latter dated August 22, 1954, from childhood acquaintance Ruth Edens:

“I have long intended to write you this letter because I have particularly wanted to say that when you used to visit me at my Balboa Island cottage, you were a shy and charming child whose appeal, it seems to me, must have reached the hearts of many people. I could never seem to get you to say much to me, but I loved having you come in and I missed your doing so after you’d gone away. I wondered about you many times and was delighted when I discovered you in the films. I hope the stories in the magazines which say you felt yourself unloved throughout your childhood, are merely press-agentry. In any case, I want you to know that I, for one, was truly fond of you and I’m proud of you for having developed enough grit to struggle through to success … I hope you are getting much happiness out of life, little Marian [sic]. I saw so much that was ethereal in you when you were a little girl that I fell sure you are not blind to life’s spiritual side. May all that is good and best come your way!”

Marilyn’s loyalty to the troops who helped to make her a star is attested in this undated letter from Mrs. Josephine Holmes, which came with a sticker marked ‘American Gold Star Mothers, Inc.‘

“My dear Miss Monroe, I was so happy to hear from Mr. Fisher about your visit to the Veterans Hospital. When I spoke to Mr. Alex David Recreation he said the veterans would be thrilled, probably the best present and tonic for them this holiday and gift giving season. I am sure it will be a wonderful memory for you, knowing you have brought happiness to so many boys, many have no one to visit with them. Thank you, and may God bless you and Mr. Miller for your kindness.”

Marilyn wore this hand-tailored black satin blouse for a 1956 press conference at Los Angeles Airport, as she returned to her hometown after a year’s absence to film Bus Stop. When a female reporter asked, ‘You’re wearing a high-neck dress. … Is this a new Marilyn? A new style?’ she replied sweetly, ‘No, I’m the same person, but it’s a different suit.’

Paula Strasberg’s annotated scripts for Bus Stop, Some Like It Hot, Let’s Make Love, and her production notes for The Misfits are available; and a book, Great Stars of the American Stage, inscribed “For Marilyn/With my love and admiration/ Paula S/ May 29-1956” (the same day that Marilyn finished work on Bus Stop. )

Letters from Marilyn’s poet friend, Norman Rosten, are also included (among them a letter warmly praising her work in Some Like It Hot, and a postcard jokingly signed off as T.S. Eliot.)

Among Marilyn’s correspondence with fellow celebrities was a Christmas card from Liberace, and a telephone message left by erstwhile rival, Zsa Zsa Gabor.

Among Marilyn’s correspondence with fellow celebrities was a Christmas card from Liberace, and a telephone message left by erstwhile rival, Zsa Zsa Gabor.

File under ‘What Might Have Been’ – two letters from Norman Granz at Verve Records, dated 1957:

“In the September 5, 1957, letter, Granz writes, ‘I’ve been thinking about our album project and I should like to do the kind of tunes that would lend themselves to an album called MARILYN SINGS LOVE SONGS or some such title.’ In the December 30, 1957, letter, he writes, ‘… I wonder too if you are ready to do any recording. I shall be in New York January 20th for about a week and the Oscar Peterson Trio is off at that time, so if you felt up to it perhaps we could do some sides with the Trio during that period.'”

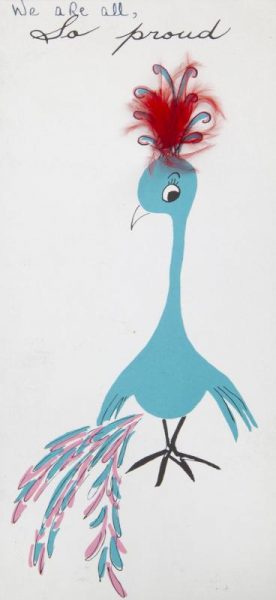

Also in 1957, Marilyn received this charming card from the Monroe Six, a group of dedicated New York teenage fans, mentioning her latest role in The Prince and The Showgirl and husband Arthur Miller’s legal worries:

“Marilyn, We finally got to see ‘Prince and the Showgirl’ and every one of us was so very pleased. We are all popping our shirt and blouse buttons. Now we will be on pins and needles ‘til it is released to the general public. You seemed so relaxed and a tease thru the whole picture and your close ups, well they were the most flawless ever. You should be real pleased with yourself. No need to tell you what we want for you to know now is that we hope everything comes out all right for Mr. Miller and real soon too. Guess what we are working on now. We are trying to scrape up enough money for the necessary amount due on 6 tickets to the premiere and the dinner dance afterwards. Well again we must say how happy we are about T.P.+T.S. and we wanted you to know it. Our best to you.”

Among the lots is assorted correspondence from Xenia Chekhov, widow of Marilyn’s acting teacher, Michael Chekhov, dated 1958. In that year, Marilyn sent Xenia a check which she used to replace her wallpaper. She regretted being unable to visit Marilyn on the set of Some Like It Hot, but would write to Arthur Miller on November 22, “I wanted to tell you how much your visit meant to me and how glad I was to see you and my beloved Marilyn being so happy together.”

In April 1959, Marilyn received a letter from attorney John F. Wharton, advising her of several foundations providing assistance to children in need of psychiatric care, including the Anna Freud Foundation, which Marilyn would remember in her will.

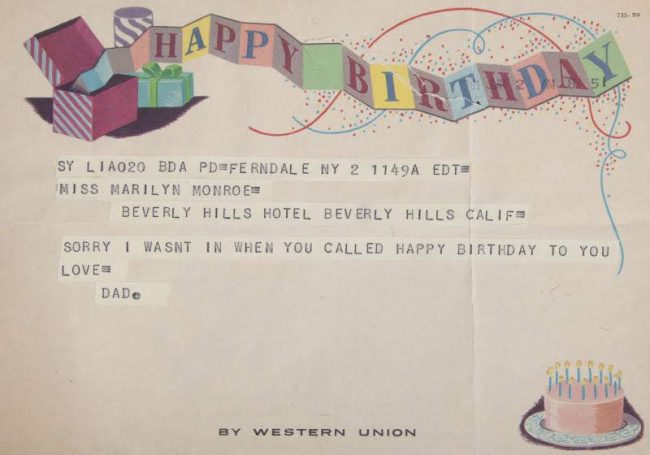

This telegram was sent by Marilyn’s father-in-law, Isidore Miller, on her birthday – most likely in 1960, as she was living at the Beverly Hills Hotel during filming of Let’s Make Love. She was still a keen reader at the time, as this receipt for a 3-volume Life and Works of Sigmund Freud from Martindale’s bookstore shows.

After Let’s Make Love wrapped, Marilyn sent a telegram to director George Cukor:

“Dear George, I would have called but I didn’t know how to explain to you how I blame myself but never you. If there is [undecipherable due to being crossed out] out of my mind. Please understand. My love to Sash. My next weekend off I will do any painting cleaning brushing you need around the house. I can also dust. Also I am sending you something but it’s late in leaving. I beg you to understand. Dear Evelyn sends her best. We’re both city types. Love, Amanda Marilyn.”

Here she is referencing her stand-in, Evelyn Moriarty, and Amanda Dell, the character she played. “Dearest Marilyn, I have been trying to get you on the telephone so I could tell you how touched I was by your wire and how grateful I am,” Cukor replied. “Am leaving for Europe next Monday but come forrest [sic] fires come anything, I will get you on the telephone.”

There’s also a June 30, 1960 letter from Congressman James Roosevelt (son of FDR), asking Marilyn to appear on a television show about the Eleanor Roosevelt Institute for Cancer Research, to be aired in October. Unfortunately, Marilyn was already committed to filming The Misfits, and dealing with the collapse of her marriage to Arthur Miller.

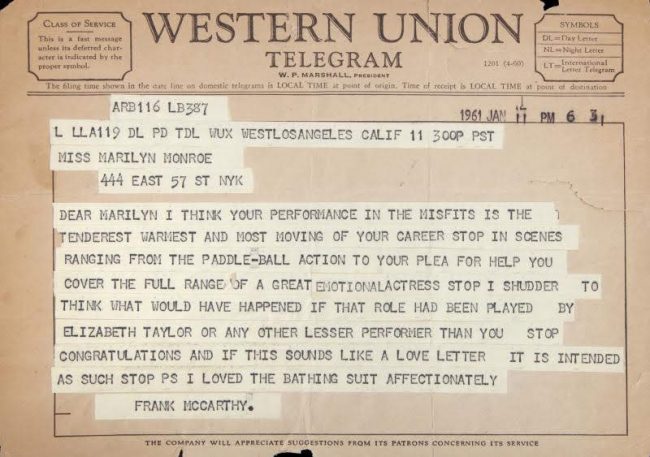

In 1961, movie producer Frank McCarthy praised Marilyn’s performance in The Misfits:

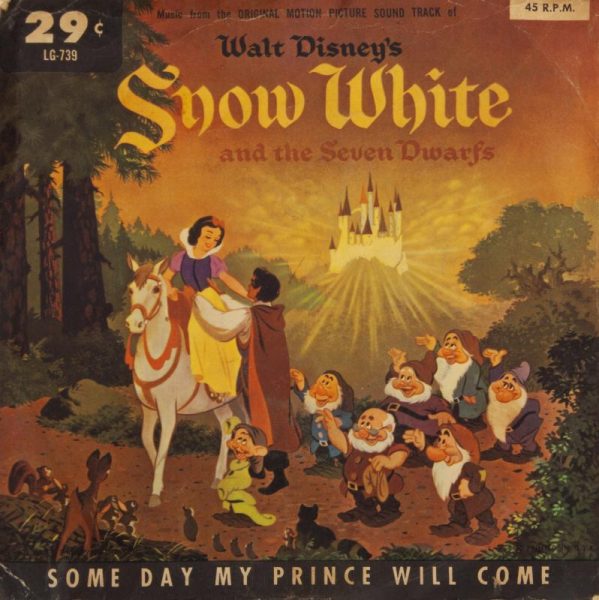

Rather touchingly, Marilyn owned this recording of ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come,’ sung by Adriana Caselotti. The record copyright is from 1961, but Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was originally released in December 1937, when Marilyn was just eleven years old.

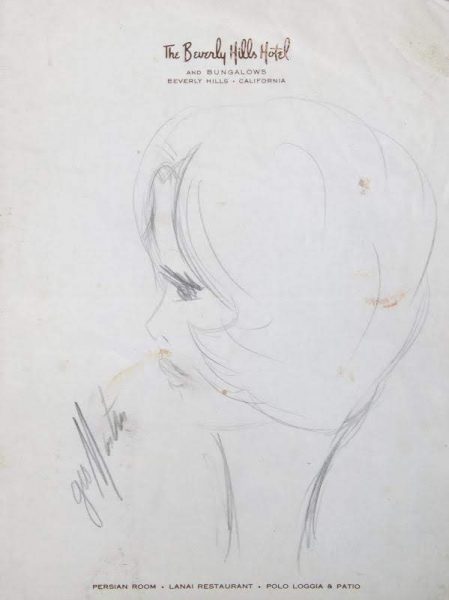

This pen portrait was sketched by George Masters, who became Marilyn’s regular hairdresser in the final years of her life.

On July 5, 1962, Hattie Stephenson – Marilyn’s New York housekeeper – wrote to her in Los Angeles:

“My Dear Miss Monroe: How are you! Trusting these few lines will find you enjoying your new home. Hoping you have heard from Mr. and Mrs. Fields by now. Found them to be very nice and the childrens [sic] are beautiful. Got along very well with there [sic] language. How is Maff and Mrs. Murray? Miss Monroe, Mrs. Fields left this stole here for you and have been thinking if you would like to have it out there I would mail it to you. Miss Monroe Dear, I asked Mrs. Rosten to speak with you concerning my vacation. I am planning on the last week of July to the 6th of August. I am going to Florida on a meeting tour. Trusting everything will be alright with you. Please keep sweet and keep smiling. You must win. Sincerely, Hattie.”

Hattie is referring to Marilyn’s Mexico friend, Fred Vanderbilt Field, who stayed with his family in Marilyn’s New York apartment that summer. She also alludes to Marilyn’s ongoing battle with her Hollywood studio. Sadly, Hattie never saw Marilyn again, as she died exactly a month later. Interestingly, the final check from Marilyn’s personal checkbook was made out to Hattie on August 3rd.

After Marilyn died, her estate was in litigation for several years. Her mother, Gladys, was a long-term resident of Rockhaven Sanitarium, which had agreed to waive her fees until her trust was reopened. In 1965, Gladys would receive hate mail from a certain Mrs. Ruth Tager of the Bronx, criticising her as a ‘hindrance’ due to her unpaid bills. This unwarranted attack on a sick, elderly woman reminds one why Marilyn was so hesitant to talk about her mother in public.

UPDATE: See results here