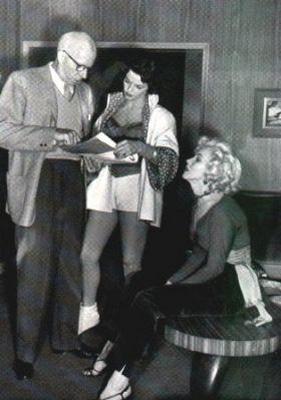

Another extract from Peter Bogdanovich’s essay on Marilyn, published in Who the Hell’s In It? (2004)

“Monroe was frightened to come on the stage – she had such an inferiority complex – and I felt sorry for her. I’ve seen other people like that. I did the best I could and wasn’t bothered by it too much. In ‘Monkey Business’, she only had a small part – that didn’t frighten her so much – but when she got into a big part…For instance, when she started her singing (for ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’), she tried to run out of the recording studio two or three times. We had to grab her and hold her to keep her there…I got a great deal of help from Jane Russell. Without her I couldn’t have made the picture. Jane gave Marilyn that ‘You can do it’ pep-talk to get her out there. She was just frightened, that’s all – frightened she couldn’t do it.”

Hawks thought Marilyn worked best in light comedy, and was sceptical of Method acting:

“Monroe was never any good playing the reality. She always played in a sort of fairy tale. And when she did that she was great…She was trying, for example, at the Actor’s Studio, to formularize her approach: She didn’t want to squander her energies. I’m not convinced it helped her at all. But that was her aim – to make it even more real.”