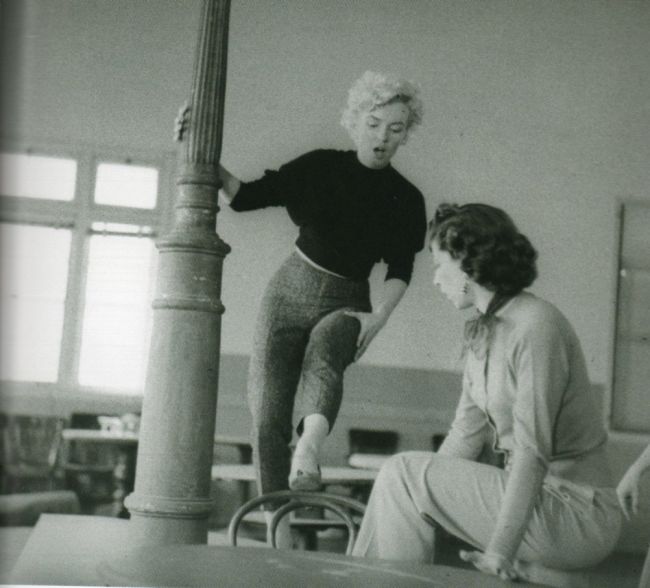

Joan Bayley, shown here coaching Marilyn for There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954), has just celebrated her 100th birthday, the Los Angeles Times reports. (Although uncredited on the film, Joan was probably assisting choreographer Jack Cole.)

“The two lines of cars — about 50 in all, decorated with posters, streamers and balloons — were parked in L.A.’s Mar Vista neighborhood as family and neighbors in masks congregated outdoors for a birthday celebration, the kind that’s come to be a national ritual during the coronavirus outbreak.

At 2 p.m. the parade began, with drivers honking and shouting birthday wishes to the woman of the hour: Joan Bayley, a former ballet instructor who worked in Hollywood musicals alongside Judy Garland, Bing Crosby and Marilyn Monroe.

Born in Canada, Bayley moved to Los Angeles at age 6 and began dancing at a neighborhood school when she was 7 or 8.

Her first experience on stage was performing in a 1934 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Hollywood Bowl. As a teenager, she trained and performed with noted choreographer Carmelita Maracci, who blended ballet with Spanish dance.

Bayley moved to New York to continue dancing with Maracci and later worked in nightclubs, performing flamenco solos for dinner guests. She returned to L.A. to pursue film work during World War II because ‘there was no touring, so companies disappeared.’

In her early years as a studio dancer, Bayley performed in ballet scenes and worked with modern choreographer Lester Horton on films including 1943’s Phantom of the Opera and 1945’s Salome, Where She Danced.

While working on the 1939 film adaptation of On Your Toes, choreographed by George Balanchine, Bayley met the man who would become her husband, Ray Weamer.

In the 1950s, Bayley began working with commercial choreographer Robert Alton — known for his discovery of Gene Kelly and his collaborations with Fred Astaire — and later became his assistant. She then worked as a choreographer herself, creating dances for television series.

She said she wanted her birthday festivities to raise awareness for the Westside School of Ballet in Santa Monica, where she taught for more than 30 years — until last year. The school is fighting for survival in the pandemic and has launched a community fundraiser to stay afloat. “