Marilyn has been chosen as one of TIME‘s 100 Women of the Year, in a project marking the magazine’s centenary. She has been selected to represent 1954, the year in which she married Joe DiMaggio; entertained US troops in Korea; filmed There’s No Business Like Show Business and The Seven Year Itch; topped the hit parade with ‘I’m Gonna File My Claim’; and then she left it all behind to study acting, and form a production company in New York.

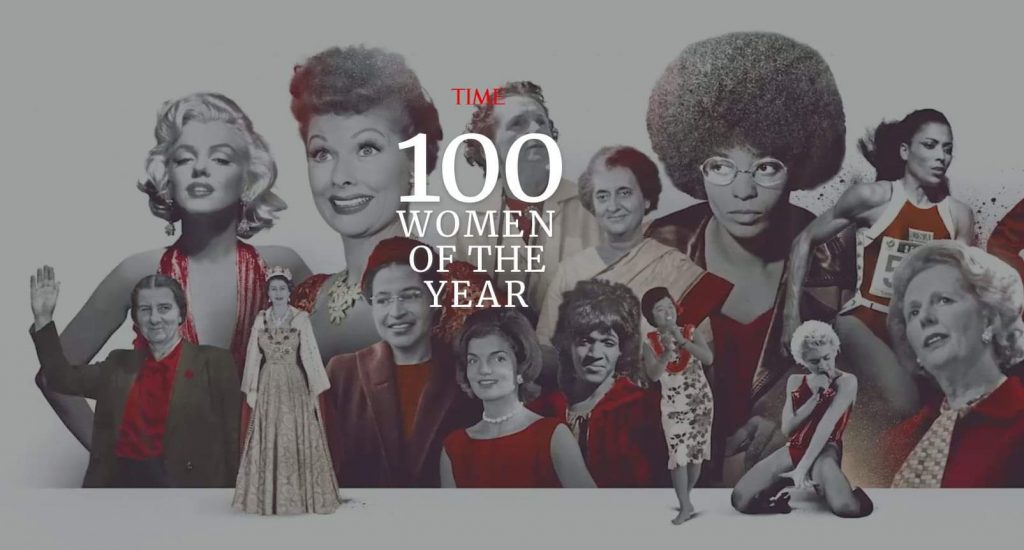

The photo shown above was taken two years previously by Frank Powolny, but remains one of the most iconic images of Marilyn. Other featured actresses include Anna May Wong, Lucille Ball and Rita Moreno. Aimee Semple McPherson, the evangelist said to have christened Norma Jeane, and Gloria Steinem, the feminist campaigner who wrote a book about Marilyn, are also listed.

“In 1954, Marilyn Monroe—already a sex symbol and a movie star—posed on the corner of Lexington Avenue and 52nd Street in New York City, for a scene intended to appear in her 1955 film The Seven Year Itch. The breeze blowing up through a subway grate sent her white dress billowing around her, an image that lingers today like a joyful, animated ghost. Monroe was a stunner, but she was also a brilliant actor and comedian who strove to be taken seriously in a world of men who wanted to see her only as an object of desire. Today, especially in a world after Harvey Weinstein’s downfall, she stands as a woman who fought a system that was rigged against her from the start. She brought us such pleasure, even as our hearts broke for her.”

—Stephanie Zacharek