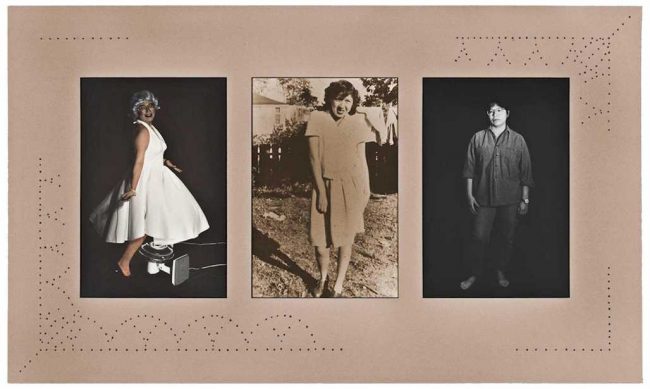

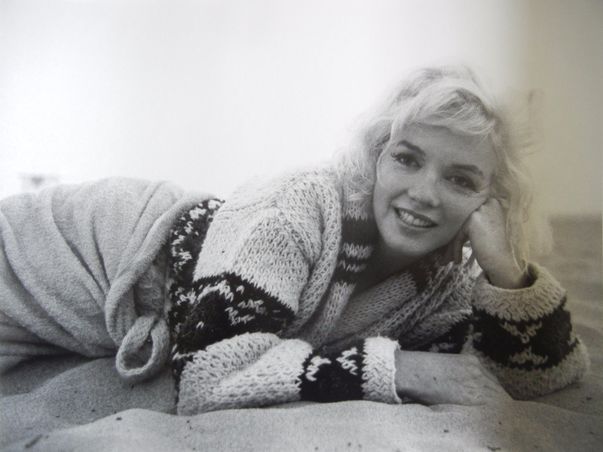

On August 4th, 1962 – a balmy Saturday evening not unlike this one – Marilyn Monroe bid her housekeeper goodnight and retired to the bedroom of her modest Los Angeles home. She would never wake again, and on Sunday morning, the world learned of her death. On this sad anniversary, here’s an ode to America’s dream girl from Sherman Alexie, an indigenous poet.

“Marilyn Monroe

drives herself to the reservation. Tired and cold,

she asks the Indian women for help.

Marilyn cannot explain what she needs

but the Indian women notice the needle tracks

on her arms and lead her to the sweat lodge

where every woman, young and old, disrobes

and leaves her clothes behind

when she enters the dark of the lodge.

Marilyn’s prayers may or may not be answered here

but they are kept sacred by Indian women.

Cold water is splashed on hot rocks

and steam fills the lodge. There is no place like this.

At first, Marilyn is self-conscious, aware

of her body and face, the tremendous heat, her thirst,

and the brown bodies circled around her.

But the Indian women do not stare. It is dark

inside the lodge. The hot rocks glow red

and the songs begin. Marilyn has never heard

these songs before, but she soon sings along.

Marilyn is not an Indian, Marilyn will never be an Indian

but the Indian women sing about her courage.

The Indian women sing for her health.

The Indian women sing for Marilyn.

Finally, she is no more naked than anyone else.–from Tourists, Part 3″