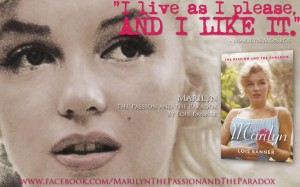

An extract from Lois Banner’s Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox was published in The Observer on Sunday.

An extract from Lois Banner’s Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox was published in The Observer on Sunday.

“I was drawn to writing about Marilyn because no one like me –an academic, a feminist biographer, and a historian of gender –had studied her. As a founder of ‘second-wave feminism’ and the new women’s history, I had dismissed Marilyn for many years as a sex object for men. By the 1990s, however, a generation of “third-wave feminists” contended that sexualising women was liberating, not demeaning, for it gave them self-knowledge and power. The students I taught were swayed by this. Had I dismissed Marilyn too easily? Was she a precursor of 1960s feminism? Was Marilyn in actual fact a feminist? Is she one of the women who changed the world’s attitude toward women?

She certainly took actions that could be called feminist. Her entire life was a process of self-formation. She was a genius at self-creation and made herself into an actress and a star. She formed her own production company, she fought the moguls to a standstill, and she publicly named the sexual abuse visited on her as a child: a major – and unacknowledged – feminist act. She refused to keep quiet in an age that believed such abuse rarely happened and when it did, the victimised girl was responsible. Such self-disclosure would become important to the feminist movement in the 1970s.

She never called herself a feminist but the term wasn’t yet in widespread use during her life, and the movement wouldn’t appear until a number of years after her death. Hedda Rosten, her secretary and close friend, identified her as ‘the quintessential victim of the male.’ Norman Rosten, Hedda’s husband, who was equally close to Marilyn, saw her relationship to feminism differently. He contended that Marilyn would have quarrelled with her ‘sisters’ on the issue of sexual liberation. She had achieved the financial and legal gains they sought. And she enjoyed her femininity, recognising its power over men. Marilyn’s stance in his eyes sounds like a post- feminist position, which privileges power over oppression and emphasises the power women possess through their femininity and sexuality.

On the other hand, one could argue that it was her fixation with her femininity – and her attitude towards it, sometimes regal and sometimes tormented – that caused her victimisation in the end. No matter how hard she tried, Hollywood and its men refused to consider her as anything more than a party girl and in the end they treated her like a slut they could use with impunity.

She commented that ‘black men don’t like to be called boys, but women accept being called girls, ‘ as though she were offended by the latter term. And she didn’t like male violence. That is apparent in the dispute she had with journalist WJ Weatherby over Ernest Hemingway. Weatherby liked Hemingway for his understanding of human nature. Marilyn didn’t like his masculine heroes. ‘Those big tough guys are so sick. They aren’t even all that tough! They’re afraid of kindness and gentleness and beauty. They always want to kill something to prove themselves!’ She praised the young people who were beginning to rebel against social conventions. In her best moments, she saw herself as part of that movement. Yet Marilyn had no gender framework to support her stance, no way of conceptualising her situation beyond her individual self, to encompass all women, whose rights were limited in the 1950s. Had she lived a few years longer, into the mid-1960s, the feminist movement could have offered the concept of sexism as a way to understand her oppression and the idea of sisterhood as a support.”