Following recent allegations of sexual harassment and assault against movie producer Harvey Weinstein, I’ve been thinking of Marilyn’s own experiences among the Hollywood ‘wolves’. (Incidentally, Weinstein produced the 2011 biopic, My Week With Marilyn.)

‘I met them all,’ Marilyn stated in her 1954 memoir, My Story. ‘Phoniness and failure were all over them. Some were vicious and crooked. But they were as near to the movies as you could get. So you sat with them, listening to their lies and schemes. And you saw Hollywood with their eyes – an overcrowded brothel, a merry-go-round with beds for horses.’

My Story was written with Ben Hecht, who may be responsible for some of the more elaborate metaphors, but he insisted it was true to the spirit of what Marilyn told him. It remained unpublished until long after her death, perhaps because it was too controversial.

When British writer W J Weatherby asked her whether the stories about the casting couch were true, Marilyn responded: ‘They can be. You can’t sleep your way into being a star, though. It takes much, much more. But it helps. A lot of actresses get their first chance that way. Most of the men are such horrors, they deserve all they can get out of them!’

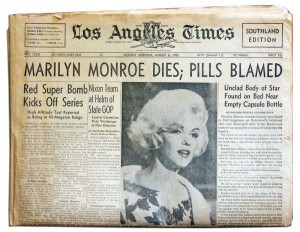

This conversation also remained private during her lifetime. Sadly, Marilyn has been retrospectively punished for her outspokenness, with tales of her supposed promiscuity circulating to this day. Even film critic Mick LaSalle, who once defended her against lurid allegations by Tony Curtis, wrote this week, ‘Ever hear of Marilyn Monroe? Of course you have. Well, she said no to very few people.’

Her relationship with agent Johnny Hyde is well-known, and some believe her friendship with movie mogul Joe Schenck was more than platonic. But the rumours of her being a glorified call-girl are utterly baseless. Several men who dated Marilyn remember her being so cautious that she wouldn’t kiss them goodnight.

Perhaps one of the most important stories relating to Marilyn and the Hollywood ‘wolves’ is her refusal to spend a weekend alone with Columbia boss Harry Cohn on his yacht while she was under contract to him in 1948. He was furious, and quickly fired her. The story is almost identical to some of the allegations being made today.

Among the many stories making the rounds lately comes from actress Gretchen Mol, who was rumoured to have been promoted by Weinstein in exchange for sexual favours. In fact, she has never been alone with him, and yet this false rumour has unjustly tarnished her reputation.

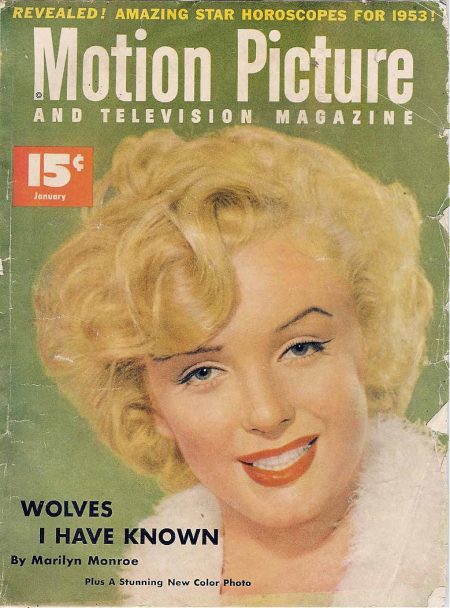

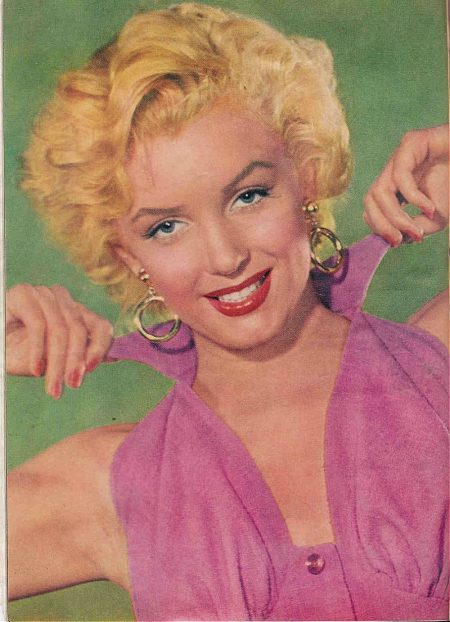

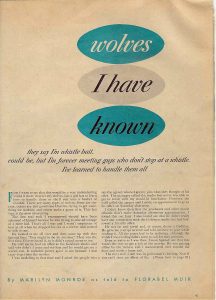

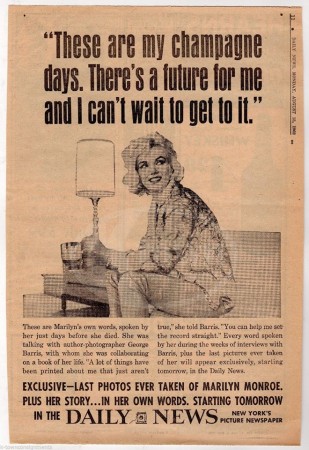

Her story reminded me a lot of Marilyn, who has been endlessly ‘slut-shamed’ simply for being honest and open about her sexuality. In January 1953, she approved a story for Motion Picture magazine which is illuminating about the harassment she experienced – I have posted it below, courtesy of the Everlasting Star boards (please click on the files below to enlarge.)

What strikes me as sad is that she almost seemed to accept it as an occupational hazard. Let’s hope that the buck won’t stop with Mr Weinstein, and that real changes will be made. Sexual exploitation is not unique to Hollywood, and until people stop blaming the victims, predators will continue to thrive.

Further Reading

Marilyn Warned Joan Collins About the Casting Couch

The

The

Over at

Over at