Alexandra Pollard takes a fresh look at Marilyn’s ill-fated last movie, Something’s Got to Give, in an insightful piece for The Independent.

“She hadn’t been on a film set for over a year when she was cast in Something’s Got to Give, a remake of the 1940 screwball comedy My Favorite Wife. Her time off had been plagued by illness and drug addiction … The accumulative physical toll had caused her to lose so much weight that she was thinner than she had been in all her adult life. The studio, Twentieth Century Fox, was delighted. ‘She didn’t have to perform, she just had to look great,’ said the film’s producer Henry Weinstein, ‘and she did.’

But in hindsight, Monroe wasn’t ready – either physically or mentally – to return to acting … ‘She was just fearful of the camera,’ said Weinstein, who recalled Monroe throwing up before scenes. Early on, he found her unconscious, in what he described as a barbiturate coma … The studio and production team had little sympathy for their star. ‘Yes this is a sick woman,’ said screenwriter Walter Bernstein, ‘but this is a movie star who’s getting her way, and who doesn’t give a damn about anybody else, and is being destructive and self-destructive.’

But watching Something’s Got to Give’s raw footage – most of which remained unseen for years after the film was scrapped – gives a very different impression. On camera, Monroe is earnest, demure, desperate to get her part right. If she messes up, she apologises profusely … She is gentle with her young co-stars, too. Alexandria Heilweil, who played her five-year-old daughter, is told to sit up straight. ‘If I do the right thing…’ says the little girl, but [George] Cukor cuts her off: ‘Be quiet.’ Monroe smiles at her. ‘You will,’ she says gently. It certainly doesn’t seem like the behaviour of someone ‘wilfully disruptive’.

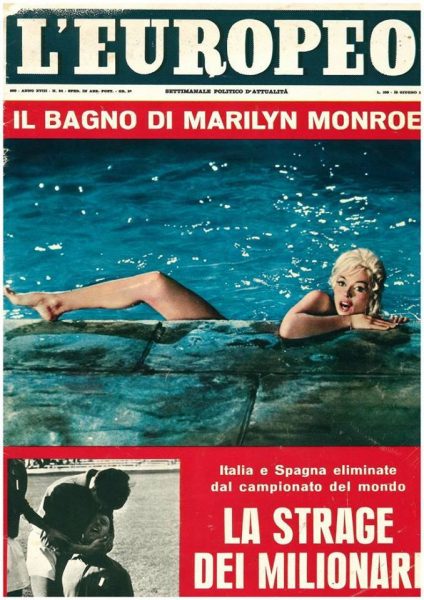

And there were a few good days. During the now (in)famous swimming pool scene, Ellen takes a late-night skinny dip, attempting to lure her husband out of his bedroom. The set was closed, but a few select photographers were allowed to stay. When Monroe ended up removing the flesh-coloured swimming costume she had been given, they were caught completely off guard. ‘I had been wearing the suit, but it concealed too much,’ she later told the press, ‘and it would have looked wrong on the screen… The set was closed, all except members of the crew, who were very sweet. I told them to close their eyes or turn their backs, and I think they all did. There was a lifeguard on the set to help me out if I needed him, but I’m not sure it would have worked. He had his eyes closed too.’ Photos of Monroe emerging from the pool, sans suit, appeared on magazine covers in over 30 countries. By all accounts, spirits seemed high.

But things went rapidly downhill. On 19 May 1962, having been too sick to work for most of the week, Monroe flew to New York for President John F Kennedy’s birthday celebrations … Monroe had gained permission to attend the event long before filming began, but [Cukor] deemed it unacceptable. In June, just a few days after Monroe’s 36th birthday, she was fired for ‘spectacular absenteeism’, and sued by Fox for $750,000 for ‘wilful violation of contract’. ‘Dear George,’ wrote Monroe in a telegram to Cukor, ‘please forgive me, it was not my doing. I had so looked forward to working with you.’

In fact, it may not have been entirely Monroe’s doing. At the same time as Something’s Got to Give was being made, Fox was haemorrhaging money on its three-hour epic Cleopatra … The studio was panicking. ‘Tensions were high, nerves were frayed, funds were low,’ wrote Michelle Vogel in Marilyn Monroe: Her Films, Her Life, ‘and it’s clear that Something’s Got to Give and Marilyn Monroe were the scapegoats for some very anxious studio executives who felt they were spinning out of control with both productions. The lesser of the films had to go.’

A few days before she died, Monroe had given an interview to a journalist from Life Magazine, and the subsequent profile was published a few weeks later. It ended with the following: ‘I had asked if many friends had called up to rally round when she was fired by Fox. There was silence, and sitting very straight, eyes wide and hurt, she had answered with a tiny, “No”.'”