Legendary fashion editor Babs Simpson has died aged 105, the New York Times reports. Born Beatrice Crosby de Menocal in 1913, she was raised in an upper-class New York family. She married William Simpson of Chicago in 1935, but returned alone to the Big Apple seven years later. She first worked as a photographer’s assistant at Harper’s Bazaar, and in 1947, began her 25-year tenure at Vogue magazine. Diana Vreeland, her boss from 1962, described Babs as ‘the most marvellous editor.” In 1972, she moved to House & Garden, where she would stay until her retirement in 1993.

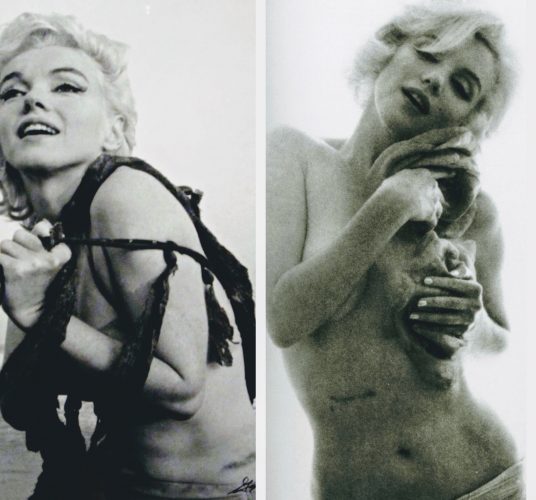

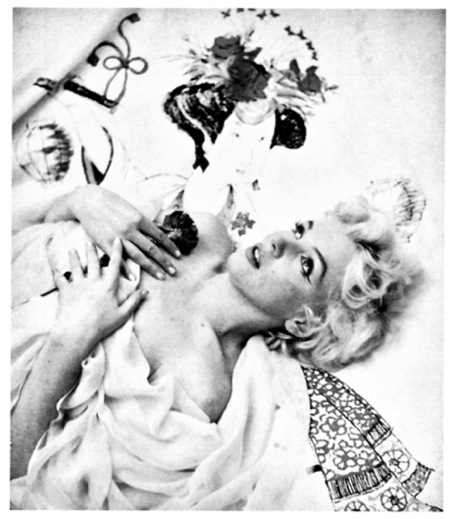

One of Babs Simpson’s most famous Vogue assignments was with Marilyn and photographer Bert Stern at LA’s Bel Air Hotel in 1962. Stern had already spent a day alone with Marilyn on June 23, working on the iconic semi-nude images where she wears a gauzy scarf, some jewellery and little else. But this wasn’t the high-fashion shoot Diana Vreeland had in mind, and another sitting was arranged for July 10-12.

“She was absolutely perfect,” Simpson said of Marilyn. Stern wrote about the fashion shoot in his book, The Last Sitting.

“The fact that Vogue were sending an editor on the shoot was a sign that they were getting serious. The first time they’d let me go off and do whatever I wanted, but now they had realised that I was on to something, and they were going to make sure they got what they wanted. Babs Simpson and I had worked together many times, and she understood me. I was sure they’d chosen her as the editor who could let me be the most creative and at the same time keep the most control. ‘Keep her clothes on,’ they’d probably told Babs. They saw where I was heading.

An editor has the difficult job of picking out all the fashions for a sitting, dressing the girl so that she looks just right, and helping the photographer in the best way possible. Babs Simpson was great because she knew when to step in and help, but she also knew how to leave the photographer alone with the model. I thought of her as ‘the needlepoint editor,’ because at every sitting, while the girl was doing her makeup or the photographer was shooting, Babs would sit on the side and work on needlepoint. Her whole house is decorated with pillows, rugs, the most beautiful things you’ve ever seen, which she made just sitting around studios over the years while the lights flashed.

Babs was bringing all the clothes, so I flew out to California with my assistant, Peter Deal, and we started setting up in the bungalow of the Bel Air … Babs arrived from the airport in a limousine. When I saw the heaps of designer dresses and fur coats being carried into the bungalow, I had to laugh.

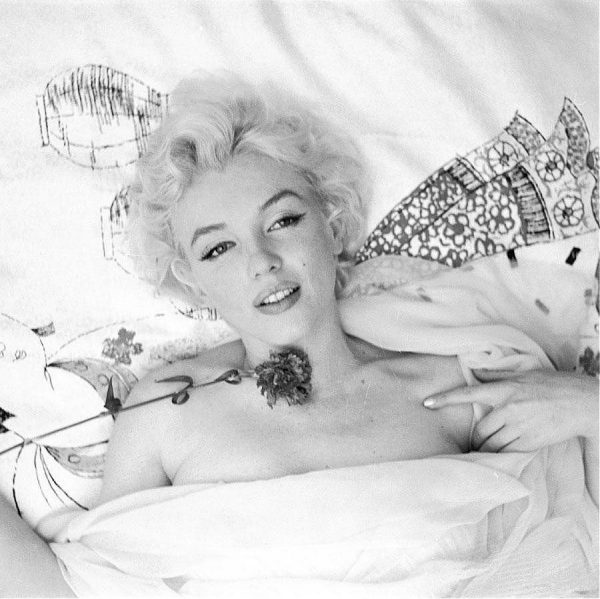

Later that morning Kenneth [Battelle] arrived. Babs had all the clothes organised and ready and she worked seriously on her needlepoint while we sat in the garden waiting for Marilyn … But when four o’clock came, Babs folded up her needlepoint, put it in her bag, and said, ‘If she isn’t here in an hour, I’m leaving’ … I said, ‘Look, just give her until five. We’re all staying here in the hotel anyway, so what’s the difference?’

Babs agreed to wait. That crisis had been averted, at least for the moment. But not half an hour later my assistant, Peter, came over to me, looking pale. In his polite way, he said, ‘Bert, I really regret having to tell you this…’

At that moment Marilyn walked in.

If I had come with an entourage this time, so had she. She was flanked by Pat Newcomb … And then suddenly Peter was well … And now that Marilyn was here, Babs cheered up, too, and went right to work. The whole crew was there, and we were in business.

I looked around at all these people, busy getting Marilyn dressed, applying her makeup, doing her hair, pouring champagne, adjusting the lights – all the process and anxiety that accompanies high fashion …This time I was going to do exactly what I’d been sent to do: take fashion pictures for Vogue. And I needed all these people, because this was going to be one tough assignment.

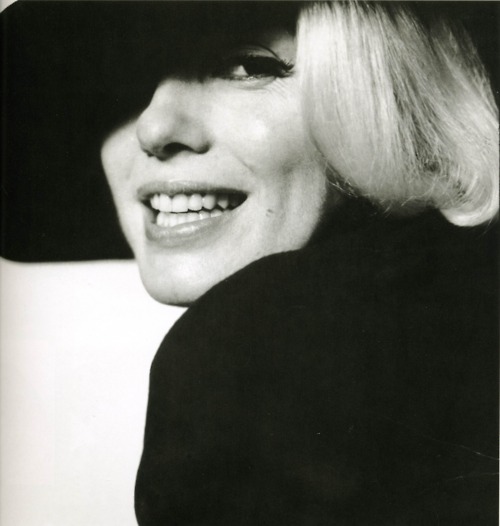

There was always a little disagreement about the accessories Babs had brought. I didn’t see the point to most of them. The white veil was almost strange enough to be interesting but the black wig … what was that all about? The last way I would have imagined Marilyn was as a raven-haired brunette … On the other hand, Babs didn’t want me to take pictures with the hat, and I thought the hat looked beautiful on her.

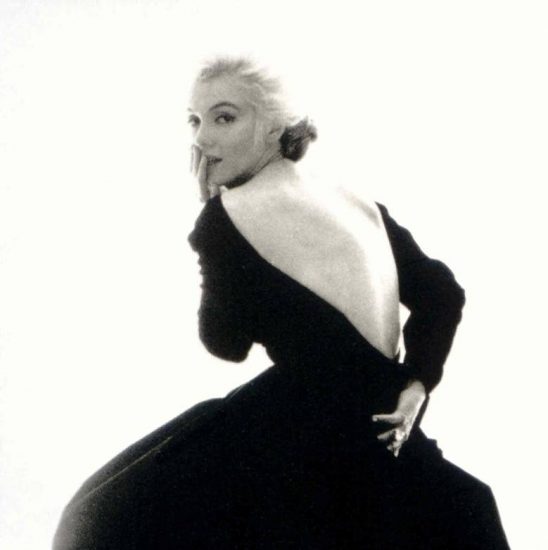

Babs had brought a lot of black dresses – the hardest thing in the world to shoot … Marilyn put on the simplest black dress. Kenneth combed her hair back. She was beautiful. All I had to do now was backlight it. That image was the essence of black and white … and blonde.

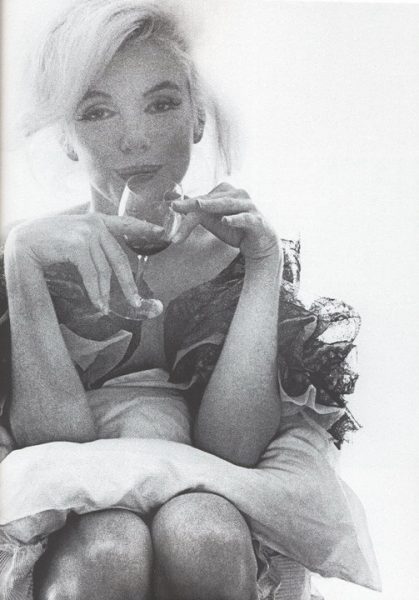

She was beginning to lose patience. I could see it on her face. She had been a good sport, but it was well after midnight, and the fashion was wearing thin … Babs had dug up another black dress, and I was ready for anything. But Marilyn had had it.

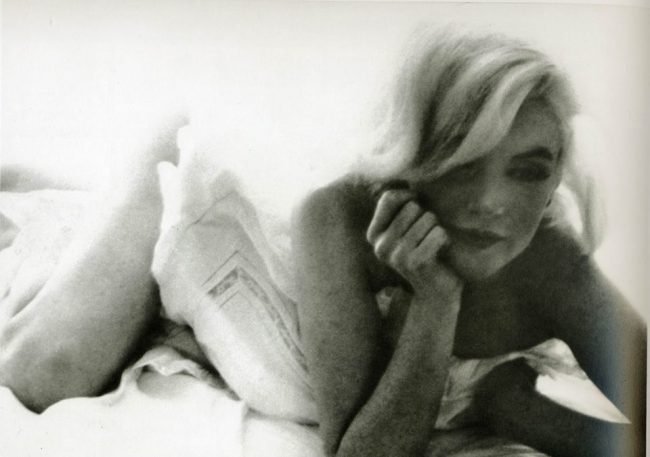

She looked around and then she walked off the white no-seam and grabbed a flimsy bed jacket that was lying casually on a chair near the strobe. I had tossed it there as a ‘no’ when we were going through the clothes earlier, because Babs said it was bad fashion, and I didn’t think much of it either. But Marilyn looked right in it.

I turned to Babs. ‘Why doesn’t everybody just leave the room and let me shoot her alone?’

Babs said, ‘I think that’s a good idea, Bert.’ Everyone got up and began to file out of the room. As they were leaving Babs said, ‘We’ll be right out here if you need us.’

‘Great,’ I said and I closed the door and locked it.

The next day she didn’t show up. Late in the morning, Babs told me that Pat Newcomb had called and Marilyn wasn’t going to work today … Then the phone rang again. It was Pat Newcomb asking whether Babs and Kenneth would come over to Marilyn’s house at one o’clock. I wasn’t invited. So Babs and Kenneth went off leaving me sitting there in the Bel Air Hotel. I didn’t feel great that day … And then Babs came back and said, ‘She’ll be here tomorrow’.

When she came in for the third shooting, everything was very different. Especially Marilyn and me. Sober, subdued, not very talkative. There was nothing to say. And then there were all these people around us again: Kenneth, Babs, Pat Newcomb, Peter Deal.

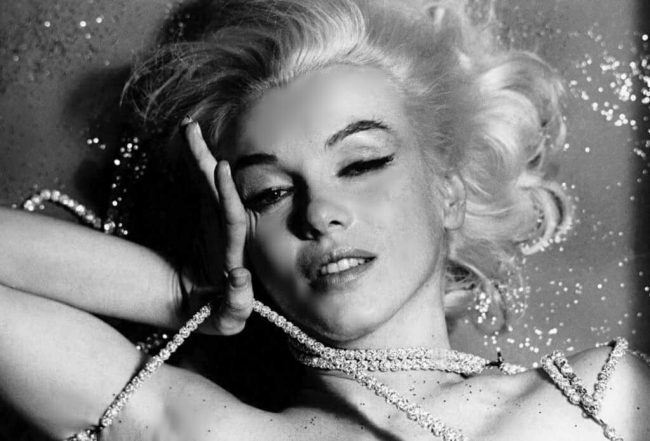

‘I want to do one more picture,’ I said. ‘A beautiful head shot.’ Babs said, ‘Oh, wonderful! We could use a great beauty shot. Kenneth will do the hair.’ Everybody was very excited.

Everybody was working. Kenneth combing Marilyn’s hair. Babs arranging a string of pearls around her neck. I was way up there in the dark, looking down on her lying there with her hair spread out.

‘Okay, I got it,’ I said, and I climbed down. It was all over. Marilyn left with Pat Newcomb, and we all packed up and got ready to leave.

As we were leaving, Babs Simpson said, ‘What’s going to happen to that poor girl?’

Poor girl?

I didn’t quite see what Babs meant. I didn’t feel sorry for Marilyn. I just figured I had done the best I could. And now I was going home.”