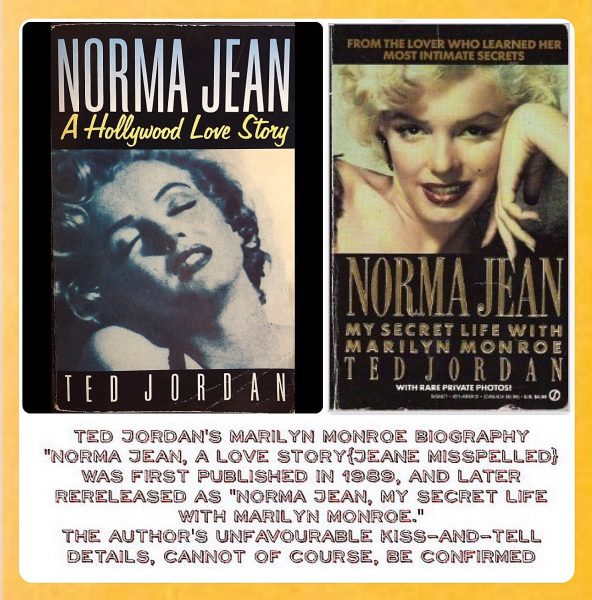

In the wake of last year’s revelations about sexual abuse in Hollywood, Marilyn’s own experiences have often been cited as historical precedent. While she certainly did experience sexual harassment, it’s notable that she managed to succeed without recourse to the fabled ‘casting couch.’ She resisted Harry Cohn’s advances; was a friend but not a mistress to Joe Schenck; and her relationship with Johnny Hyde was based on real affection. As for Darryl F. Zanuck – perhaps the most significant Hollywood figure in her career – they were never close, and Zanuck himself admitted that Marilyn’s triumphs were of her own creation.

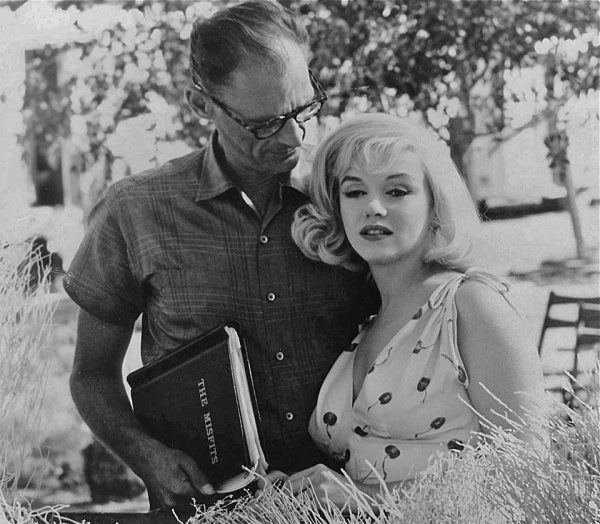

In a new article for the Daily Beast, Maria Dahvana Headley turns her attention to Arthur Miller, claiming that he ‘smeared’ Marilyn and ‘invented the myth of the male witch hunt.’ She begins with his 1952 play, The Crucible, based on the Salem witch trials of 1692, but widely perceived as an allegory for the contemporary ‘red-baiting’ crusade by the House Un-American Activities Committee, in which Arthur would later be implicated – but ultimately exonerated.

Arthur and Marilyn first met in 1951, when he was still married. There was a strong attraction between them, and they corresponded intermittently thereafter. Headley is not the first to argue that the adulterous affair between the teenage Abigail Williams and John Proctor might have been inspired by his conflicted feelings for Marilyn – Barbara Leaming also suggested this in her 1999 biography, Marilyn Monroe. Many historians have pointed out that Miller’s depiction of these protagonists is not accurate – Abigail was still a child, and there was no affair with Proctor. This mooted association between Abigail and Marilyn is purely speculative, however, and Miller would hardly be the first playwright to fictionalise events. (For a factual account of the trials, I can recommend Stacy Schiff’s The Witches.)

But Headley goes further still, conflating the story of Arthur rubbing Marilyn’s feet at a Hollywood party (as later told by Marilyn to her acting coach, Natasha Lytess) with an incident noted in the Salem court reports that inspired The Crucible, of Abigail touching Proctor’s hood and then becoming hysterical, crying out that her hands were burning. ‘Women, unless they are very devout and very old, The Crucible tells us, are unreliable and changeable,’ Headley writes. ‘They’re jealous. They’re vengeful. They’re confused about sex and about love. They might, given very little provocation, ruin the life of a good man, and everything else in the world too.’

Headley is on firmer ground with her interpretation of After the Fall, Miller’s 1964 play which featured a self-destructive singer, Maggie, who marries lawyer Quentin – a relationship widely acknowledged to be based on Arthur’s marriage to Marilyn (though he seemingly remained in denial.) ‘Maggie uses sex to bewitch Quentin out of his marriage to the long-suffering Louise,’ Headley writes, ‘marries him herself, and then becomes a catastrophe. By the end of the play, Quentin is wrestling a bottle of pills out of her hand. She drains their bank accounts, uses all of his energy for her own career, and demands endless love.’

This is a harsh portrayal of Marilyn, and many felt that Miller went too far. However, it is not without compassion. By focusing on the real-life parallels, Headley sidelines the broader themes of both plays. The Crucible was about the persecution of innocents for imaginary crimes, and After the Fall was, at least partly, a reckoning with the Holocaust (as well as Arthur’s own guilt over Marilyn’s death.) While the victims of the Salem witch hunts were mostly women, it is not surprising that Miller would identify more closely with a male protagonist. And the horrors of his own time – the holocaust, and HUAC – claimed both men and women.

In his final work, Finishing the Picture, Arthur revisited the troubled production of The Misfits. ‘She’s ceased to be the sex goddess she’s supposed to be,’ Headley says of Kitty, the Marilyn-figure in the play. ‘Instead, she is once again a naked girl in the woods, glimpsed running from the rest of the story, and in her flight, she makes everyone around her miserable … In Miller’s final statement on the matter, she’s what the world might become if a woman wanted too much consideration.’

In November 2017, Anna Graham Hunter accused actor Dustin Hoffman of sexually harassing her as a 17 year-old intern on the set of Death of a Salesman, the 1985 TV adaptation of Miller’s most famous play. According to the Hollywood Reporter, film director Volker Schlondorff responded with the glib remark that ‘I wish Arthur Miller was around, he would find the right words, but then he might get accused of sexually molesting Marilyn Monroe.’ Since then, other women have come forward with allegations against Hoffman. Whatever Schlondorff may believe, it’s impossible to know what Arthur would have made of the scandal, but it’s worth remembering that he reportedly disliked Hoffman’s performance in the prior stage production, although it had won a Tony award for Best Revival.

Anna Graham Hunter’s story needs to be heard, as do countless other victims of predatory men. In Marilyn’s case, however, there’s a danger of rewriting history. While Headley’s literary critique is valid and interesting, her attempt to recast Miller as an abuser of women is grossly unfair.