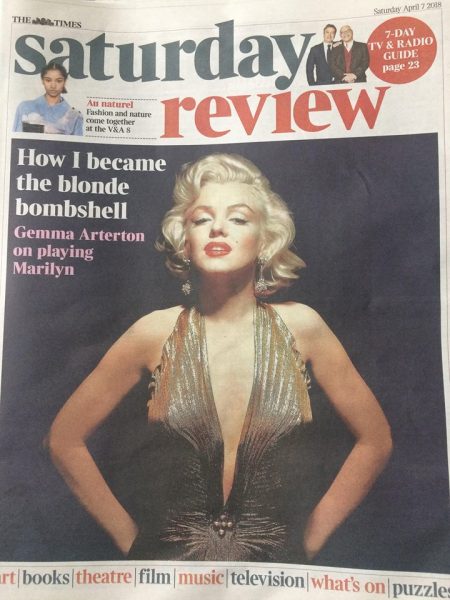

Following last weekend’s viewing party, Tony and Manohla weigh up the feedback for Some Like It Hot in the New York Times. While the drag storyline is seen as ahead of its time, Marilyn’s ‘dumb blonde’ persona was also more complex than it may have appeared.

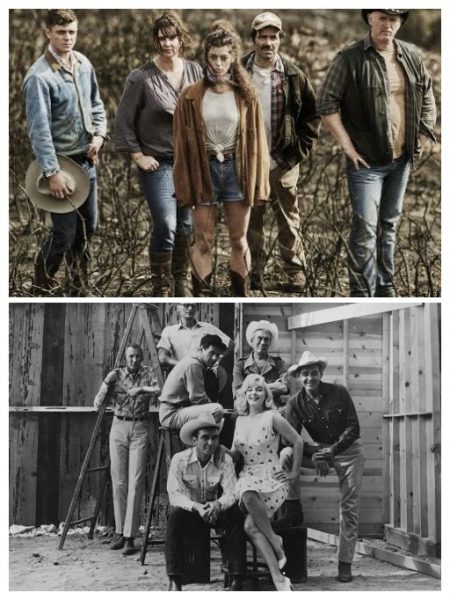

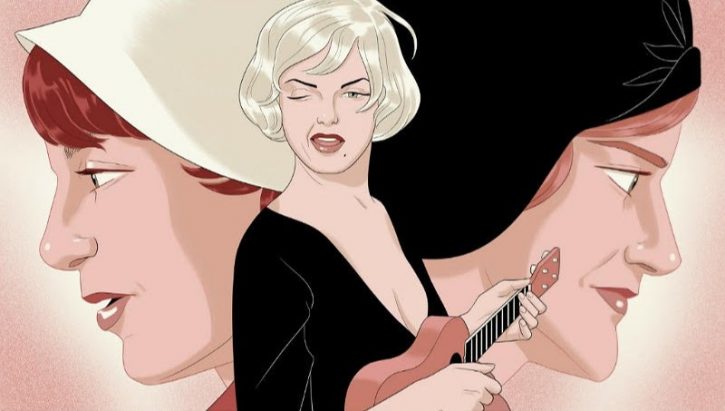

“It’s a complicated picture, bracingly ahead of its time in some ways, wincingly dated in others. Lemmon and Joe E. Brown (as the millionaire Osgood) seem to make a case for gay marriage more than half a century before the Obergefell decision. At the same time, one of the sources of the movie’s enduring appeal — Monroe’s performance as the lovelorn ukuleleist Sugar ‘Kane’ Kowalczyk — is also sometimes a source of discomfort. It can be hard to disentangle sex appeal from exploitation, or to avoid seeing the shadow of Monroe’s profound unhappiness in Sugar’s melancholy moments.

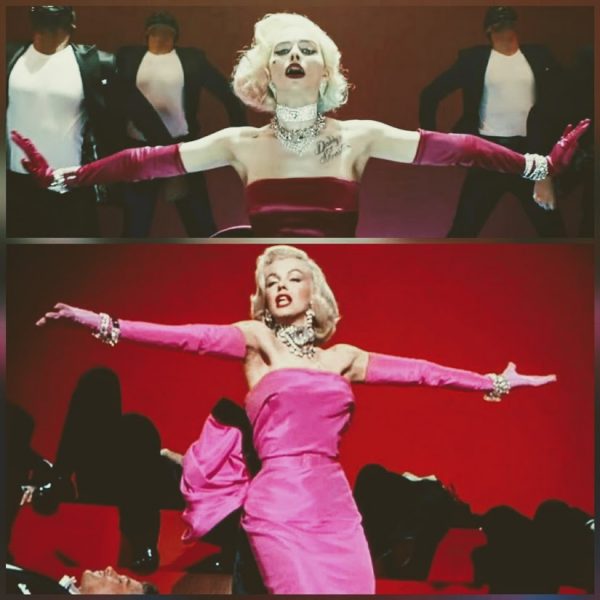

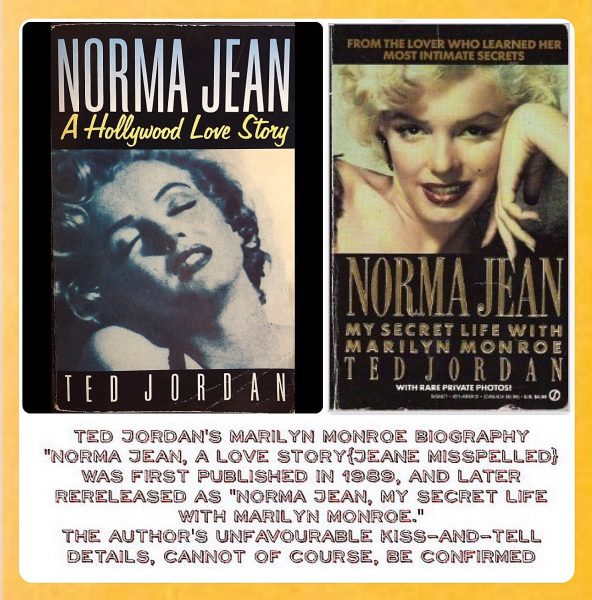

‘I think there have been more books on Marilyn Monroe than on World War II,’ Wilder once said, ‘and there’s a great similarity.’ Whatever he meant by that, it’s true that she has been posthumously transformed from sex object to object of interpretation. Some Like It Hot certainly uses her to generate erotic heat, in that almost invisible Orry-Kelly gown and in that steamy make-out scene with Curtis. But surely Sugar is more than eye candy. Lemmon and Curtis are justly celebrated for their winking, campy, affectionate sendups of femininity, but isn’t Monroe doing something equally sophisticated?

“Sugar’s masculine aggression as she seduces a sexually repressed Josephine/Cary Grant/Tony Curtis turns another male/female encounter completely inside out. The sex object playing the role of sex predator works to perfection thanks to Monroe’s performance. We realize again that what we see is seldom what we get. After all, as Sweet Sue tells us, ‘All my girls are virtuosos.’” Conrad Bailey, Prescott, AZ

What she’s doing is as knowing as the rest of the film is, which is why it remains such a fascinating object to revisit again and again. Wilder was a virtuoso and seems to have been a bastard or at least played one in life. Ed Sikov opens his biography of him with a quote in which Wilder says, ‘In real life, most women are stupid,’ adding that so are those who write celeb bios. Sikov isn’t alone in seeing, as he puts it, ‘a streak of misogyny’ in Wilder’s career, though I see him as an equal opportunity cynic, one who gave women fantastic roles.

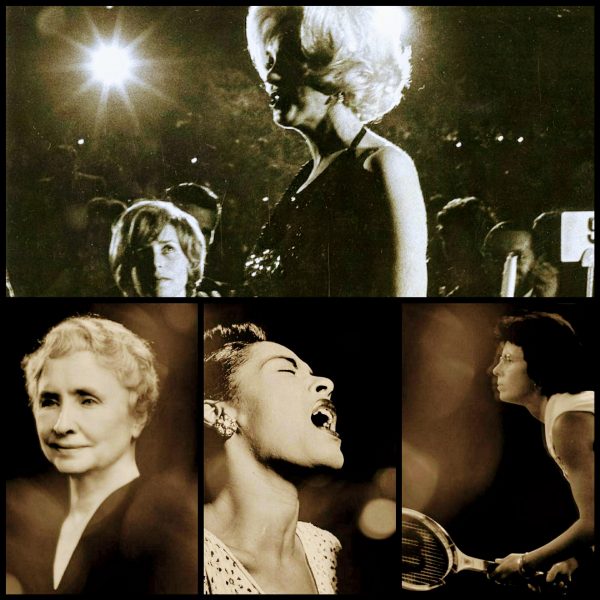

And Sugar is a role and as much a caricature of femininity as Josephine and Daphne are. Monroe is often rightfully remembered as a victim, including of the movie industry, but it’s crucial to see that she helped create this iconic blond bombshell called Marilyn Monroe.”