Another extract from film critic Richard Dyer’s essay, ‘Monroe and Sexuality’, published in his 1986 book, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, focuses on Cherie’s speech to Elma (Hope Lange) in Bus Stop (1956), and also her performance in The Misfits (1961.)

“Time and again, Monroe seems to buy into the ‘progressive’ view of sex, a refusal of its dirtiness – but that means buying into the traps of the sexual discourses discussed above: the playboy discourse, with women as the vehicle for male sexual freedom, and the psycho discourse, with its evocation of the ineffable unknowability of sexuality for women. The choice of roles from ‘Bus Stop’ on indicates the conundrums the image is caught up in. Only ‘The Misfits’ begins to hint at a for-itself female sexuality, and then casts it utterly within the discourse of female sexuality as formlessness. The men in the film look on, unable to comprehend her sensuality; grasping a tree she looks out at them/us with a hollow expression of beatitude, straining to express what is already defined as inexpressible.

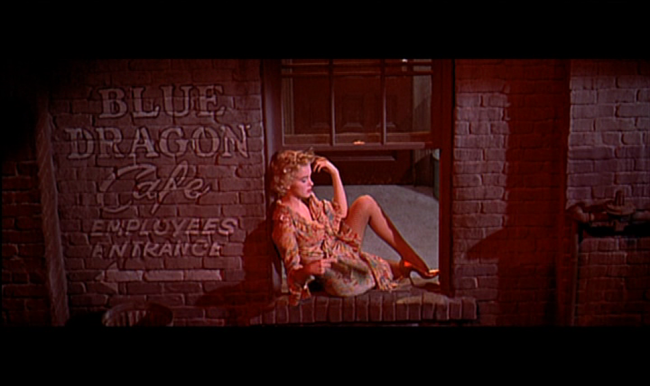

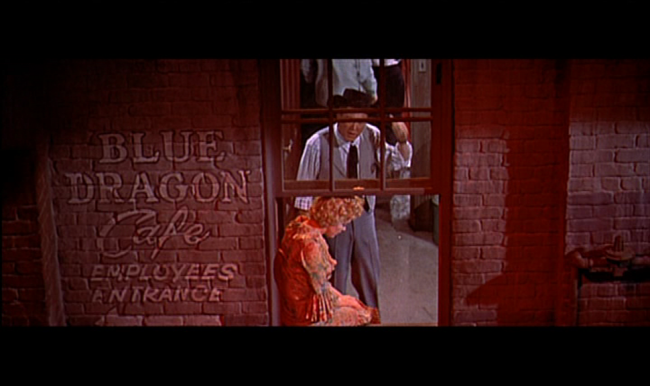

Yet some of her later films do contain hints of the struggle, traps and conundrums of the fifties discourses of sexuality. ‘Bus Stop’ is probably the most extended example. It is possible, without straining too much against the drift of the film, to read Cherie/Monroe not just as the object of male desire but as someone who has to live being a sex object.

Cherie/Monroe’s longest dialogue comes in scenes with other women characters, and has thereby the quality of unburdening herself rather than putting on an act or standing up to men. With the waitress Vera (Eileen Heckart), she expresses her ambition to be a singer and Hollywood actress, referring to the lack of respect she has had up to now. With the young woman on the bus, Elma (Hope Lange), she speaks of the ideal man she is looking for, a notion of a man who combines traditionally masculine and feminine qualities:

‘I want a guy I can look up to and admire – but I don’t want him to browbeat me…I want a guy who’s sweet to me, but I don’t want him to baby me…I want a guy who has some real regard for me, aside from all that loving stuff.’

None of this is desperately radical or progressive; the ambition is mainstream individualism (‘I’m trying to be somebody’), the ideal man is a sentimental fantasy. But both are located in the consciousness of a dumb showgirl type, and given a legitimate voice by the seriousness of the performance, of the way in which they are filmed, and, especially, by virtue of the fact that they are spoken to another woman. The ambition and fantasy are not in the slightest ridiculed, and they have the effect of throwing into relief the showgirl role that Cherie/Monroe is playing.”

The monologue in Bus Stop is rightly considered one of the high points of Marilyn’s acting career. Unfortunately, it was heavily cut – which, Monroe believed, robbed her of an Oscar nomination.

In her 2007 book, Platinum Fox, Cindy De La Hoz revealed the text of Marilyn’s speech in its entirety. The edited parts are emboldened here.

Cherie: I don’t know why I keep expecting myself to fall in love, but I do.

Elma: I know I expect to, some day.

Cherie: I’m seriously beginning to wonder if there’s a kind of love I have in mind…naturally, I’d like to get married and have a family and all them things but…

Elma: But you’ve never been in love?

Cherie: I don’t know. Maybe I have and I didn’t know it. Maybe I’m expecting it to be something it ain’t. I just feel that, regardless how crazy you are about some guy, you’ve got to feel…and it’s hard to put into words, but…you’ve got to feel he respects you. Yes, that’s what I mean…I’ve just got to feel that whoever I marry has some real regard for me, aside from all that loving stuff. You know what I mean?

Elma: I think so. What will you do when you get to Los Angeles?

Cherie: I don’t know. Maybe if I don’t get discovered right away, I could get me a job on one of the radio stations there. Even singing hillbilly if I have to. Or else, I can go to work in Liggett’s or Walgreen’s. Then after a while I’ll probably marry some guy, whether I think I love him or not. Who am I to keep insisting I should fall in love? You hear all about love when you’re a kid and just take it for granted that such a thing really exists. Maybe you have to find out for yourself it don’t. Maybe everyone’s afraid to tell you.