The Brothers Mankiewicz, a dual biography of screenwriters Joseph and Herman Mankiewicz, has just been published. Herman, the elder brother, boasted credits for Dinner at Eight, The Wizard of Oz, and Citizen Kane; while Joe, eleven years his junior, also worked as a producer and director, and gave a little-known actress a big break.

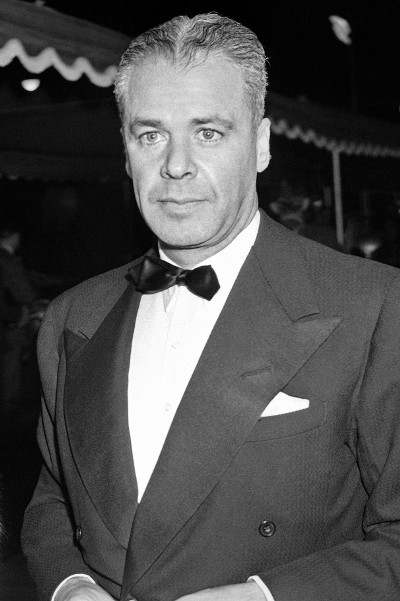

In 1950, Marilyn won a minor role in All About Eve. As an ambitious starlet, notes author Sydney Ladensohn Stern, she had “unusually good lines,” and given her subsequent rise, the performance has “unintended retrospective importance.” Stern then claims that she was hired “mostly as a favour to her mentor/lover, William Morris agent Johnny Hyde.” While Hyde’s influence may have helped, Joe Mankiewicz would later say he had chosen Marilyn after seeing her in The Asphalt Jungle, noting that she had “a sort of glued-on innocence” which made her ideal for the part.

Stern also claims that the story about Marilyn and Joe Mankiewicz discussing Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, which she had picked up in a bookstore, is unreliable because she had actually been given the book by her acting coach, Natasha Lytess. But however Marilyn may have acquired the book (and she already had a charge account at a Los Angeles bookstore), both her telling of the story, and Joe’s, emphasise her understanding of its themes. Her personal copy was auctioned by Christie’s in 1999.

In 1954, Marilyn contacted Mankiewicz expressing her wish to play nightclub singer Miss Adelaide, the long-suffering fiancee of Nathan Detroit (Frank Sinatra), in his upcoming musical, Guys and Dolls. Producer Sam Goldwyn also wanted Marilyn to star, but the role went to stage actress Vivian Blaine. According to Stern, Mankiewicz joked that “he couldn’t imagine [Marilyn] waiting fourteen years for a guy.” (You can read more about Guys and Dolls here.)

However, Monroe biographer Barbara Leaming believed the rejection was rather more personal, while Mankiewicz would later make disparaging remarks about her to another author, Sandra Shevey. He dismissed outright the notion that Marilyn was a victim of Hollywood, although he was no stranger to industry disputes and volatile stars.

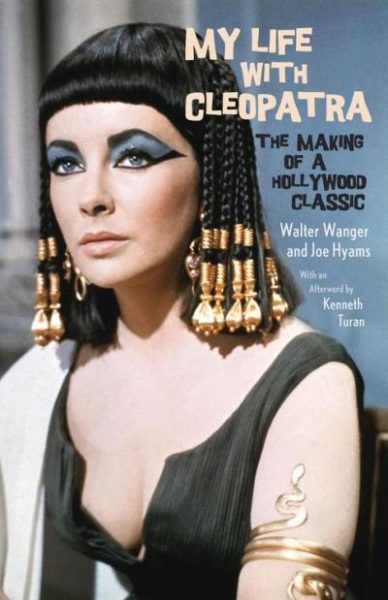

In 1961 Mankiewicz became mired in Fox’s notoriously fraught production of Cleopatra, which took him two more years to complete, and almost bankrupted the studio. In fact, the Cleopatra debacle is thought to have indirectly caused Marilyn to be fired from her final movie, Something’s Got to Give. (During his brief, inglorious tenure as studio boss, Peter Levathes also sacked Elizabeth Taylor from Cleopatra. She was swiftly re-hired, but Marilyn would pass away before negotiations for her own reinstatement were realised.)

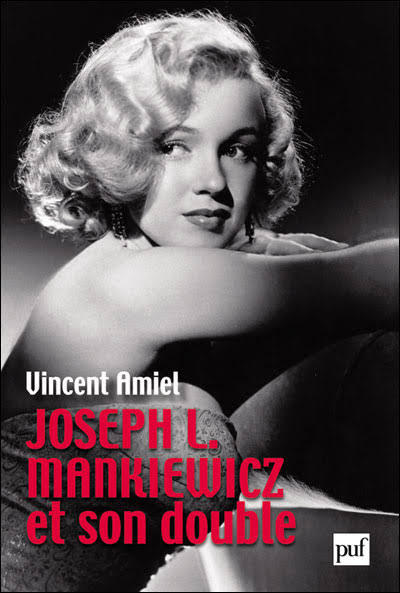

While The Brothers Mankiewicz contains little new information about Marilyn, it’s a valuable resource about two men who shaped Hollywood’s golden age. In her 1954 memoir, My Story, Marilyn praised Joe as “a sensitive and intelligent director”, and in 2010 she was featured on the cover of a French tome, Joseph L. Mankiewicz and His Double.