Writing for Nyack News & Views, Mike Hays tells the story of Marilyn and Arthur Miller’s visit to novelist Carson McCullers’ home on February 5, 1959. (What the article doesn’t mention, however, is that Marilyn and Carson had been friends since 1955, when they were both residents of Manhattan’s Gladstone Hotel. And although Arthur didn’t recall Marilyn having read any of Carson’s books, she did own a copy of The Ballad of the Sad Cafe.)

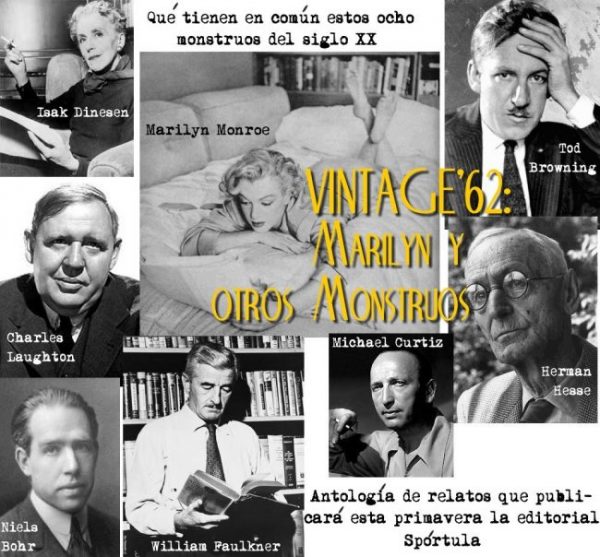

“As a transplanted New Yorker and a famous author, McCullers had close friendships with the famous, including Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote. She had always wanted to meet Isak Dinesen, the author of one of her favorite books, Out of Africa. McCullers met Dinesen at a dinner party following an arts awards in New York City.

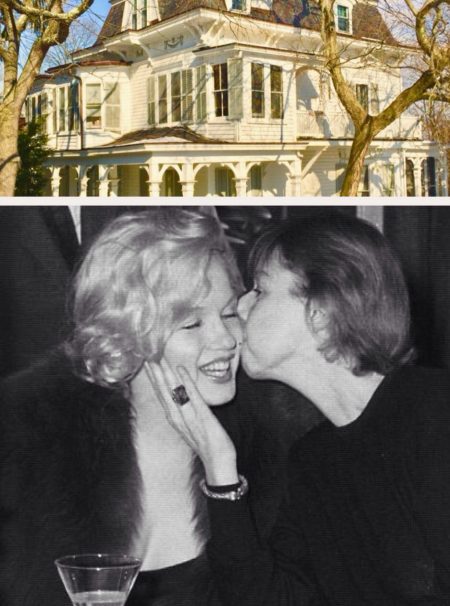

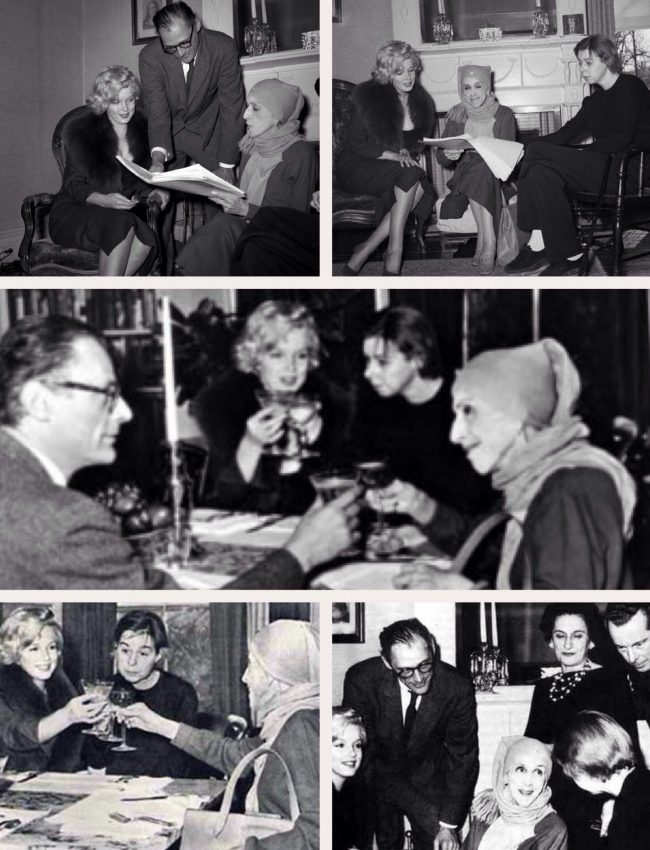

Learning that Isak wanted to meet Marilyn Monroe, she asked Marilyn’s husband at the time, Arthur Miller, who was seated at a table nearby if the ‘Millers’ would come to lunch on February 5, 1959. Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe picked up the 74-year old Dinesen and drove to Nyack. Monroe, 33, had just finished Some Like It Hot. She arrived dressed in a black sheath and fur stole. Isak wore a scarf wrapped around her head as a turban. The guests were fashionably late.

They dined on oysters, white grapes, champagne and a soufflé. They were all smokers including Monroe, although no ashtrays can be seen in the luncheon photos.

Marilyn told a story about once trying to make pasta. She was late, as usual, and the pasta was undercooked, so she tried to complete her attempt at cooking by heating the pasta with a hair dryer. Frail Dinesen told many stories and enjoyed talking to Ida Reeder, Carson’s housekeeper.

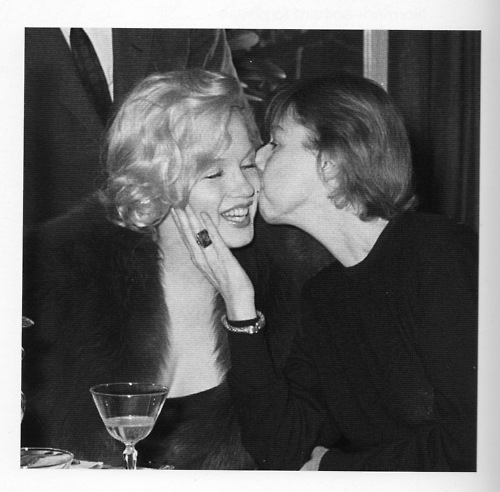

Towards the end of the afternoon, as the story goes, Carson put a record on the phonograph and invited Marilyn and Isak to dance with her on a marble table. They took a few steps in each other’s arms. Carson remembers that this was the ‘best’ and ‘most frivolous’ party she had ever given, and she expressed ‘pleasure and wonderment at the love, which her guests seemed to express for each other.’

It is improbable that the frail and ill Carson McCullers, her muscles shriveled, did much dancing and certainly not on a table. But she retold the story again and again over the rest of her life, perhaps telling the story the way she would have wanted it if she were not ill.

Others don’t remember the dancing although they do remember the lunch. Some time later, Miller said that Marilyn had never read anything by Carson, although she may have seen her play, A Member of the Wedding. He did sense a spontaneous sympathy between the women. Miller doesn’t remember the dancing, a story that seemed to have a life of its own in the media.”