“She felt there was ‘a huge gap’ between the cozy storyteller she saw at home, who enjoyed woodworking, and the cool intellectual she saw in interviews. ‘He had a remoteness in interviews, because he was a shy person and he was very protective of himself, understandably at that point,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘It was a feeling like, his warmth and his humor would never really come through.’

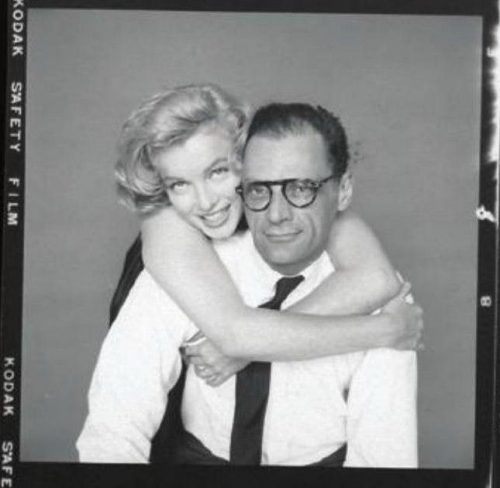

Ms. Miller found that portraying her father’s passionate romance with Monroe was ‘very tricky.’

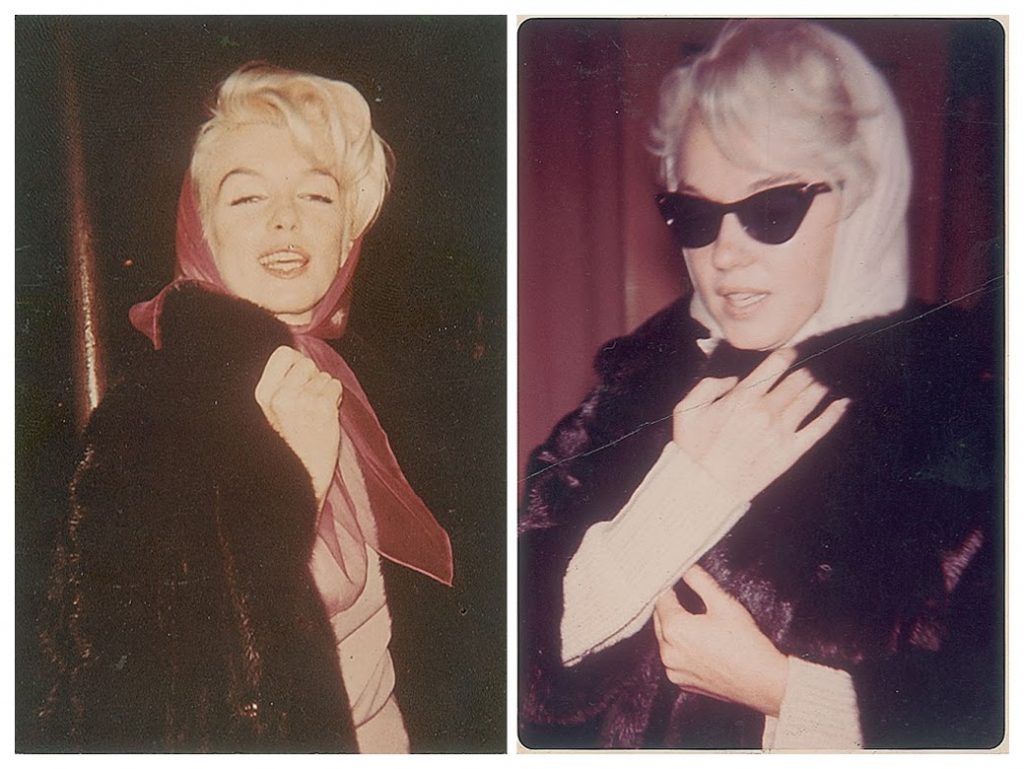

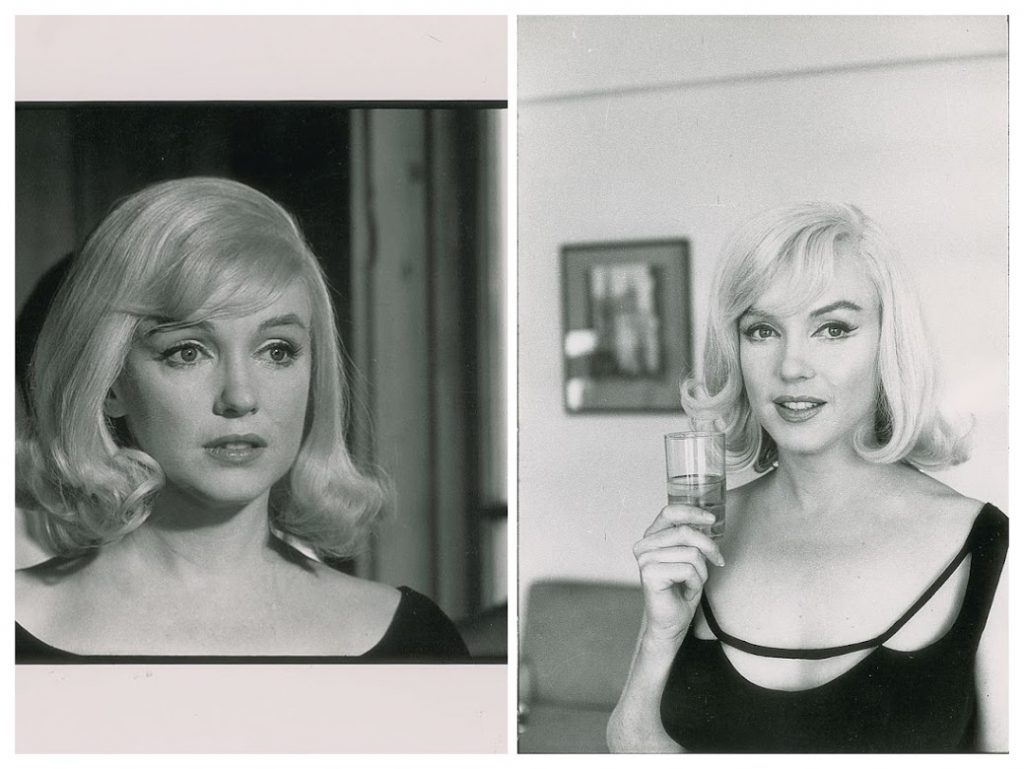

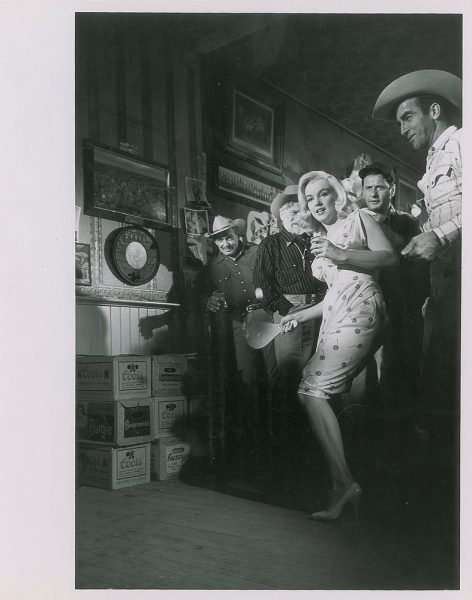

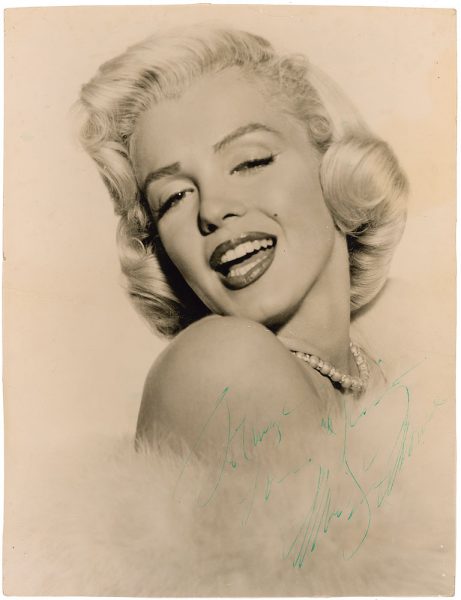

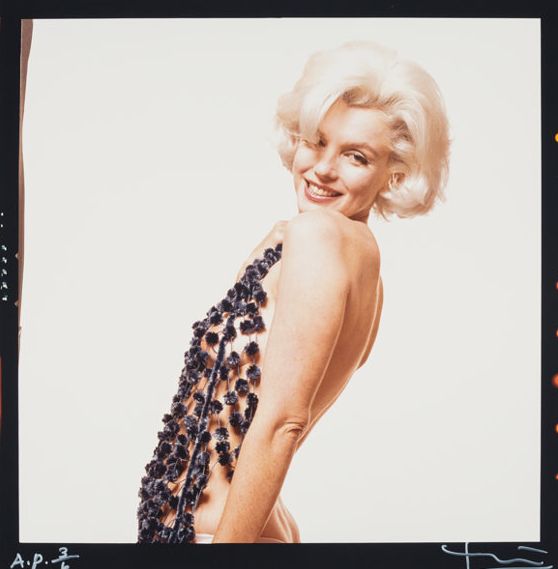

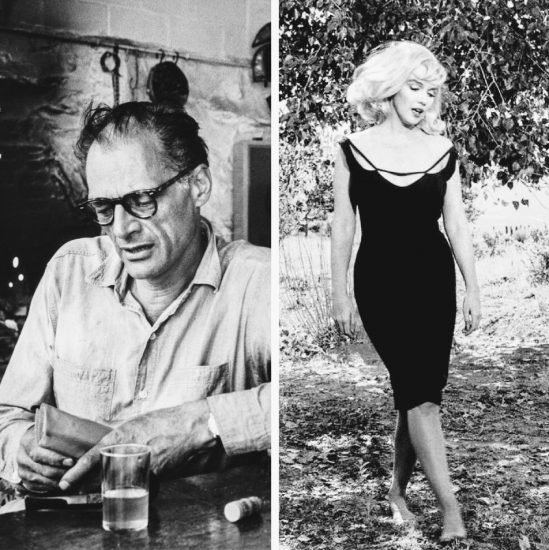

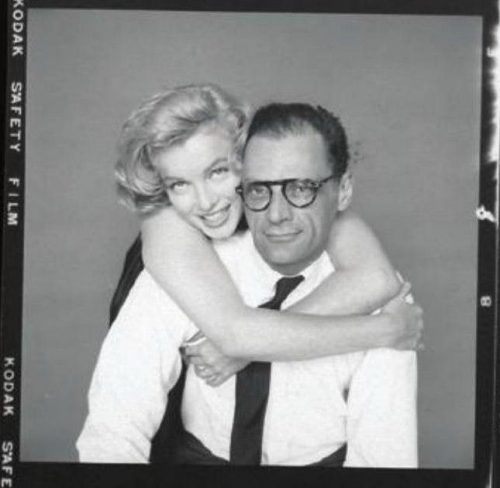

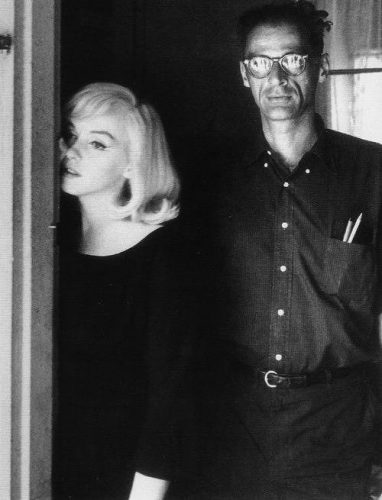

‘I felt sometimes almost that I shouldn’t be in the room, I shouldn’t know all this stuff,’ she says. ‘There was this one moment that we created a scene with still pictures where he seems to be looking at her and she’s standing there and he says, You’re the saddest girl I’ve ever met. It was weird, but that was also the moment where I sort of transformed from a daughter into a filmmaker. And I also ended up sort of seeing how she was just a person, you know? Because there’s so much smoke around her. She would even tend to take up huge amounts of space in the film. I was constantly trying to cut it down again, because she has so much light coming out of her. So much charisma. I just said, ‘O.K., how can we penetrate the mystery a little bit of this woman and this man and in the end find some clarity?’

She puts one of her father’s searing love letters to Marilyn up on screen, reading: ‘So be my love as you surely are. I think I shall be less furiously jealous when we have made a life together. It is just that I believe that I should really die if I ever lost you. It is as though we were born the same morning when no other life existed on this earth. Love, Art.’

The romance that began with such passion devoured itself. ‘He was really, really worn down,’ his daughter says. ‘He hadn’t gotten any work done for a long time, and this was a man who completely identified himself as a writer. And that had been put away, barring The Misfits, which was itself excruciating. But I think she had had it, too. They were not matched. They tried and they just bungled it.’

“She was the rose and he was definitely the gardener. But he’s more of a rose and he needed a gardener. People can only play the other part for so long.’

‘You can’t really save someone,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘You have to acknowledge that you’re you and I’m me, and your powers don’t extend to being a savior. My impression is for whatever reason, I don’t know exactly, but she saw death was luring her for a long, long time, and I think that had to be her end point.’

The director originally put in Ms. Monroe’s pregnancy during Some Like It Hot, and her subsequent miscarriage, but then cut it. ‘We had a version where we see her going into the hospital,’ she says, ‘but it’s that line of what’s gossip and what’s getting to the meat of the matter?’

I tell Ms. Miller that I have always had a dim view of her father’s treatment of Marilyn: because of his play After the Fall, about a Jewish intellectual in New York married to a needy show business idol who commits suicide, which he at first denied was even about Marilyn; and also because he crushed her during their marriage by leaving an open journal for her to find, with an entry about how she had disappointed him and embarrassed him in front of his brainy peers.

‘Maybe he did it unconsciously,’ Ms. Miller says about her father leaving out his journal. ‘But you know what? The unconscious, you never know.’

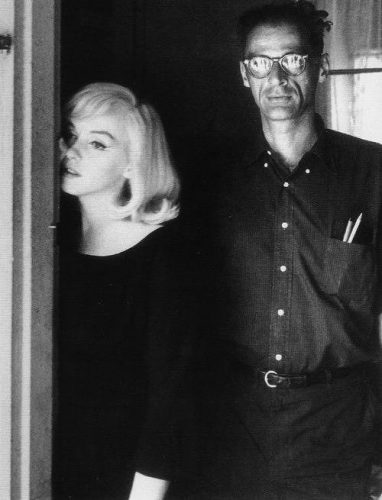

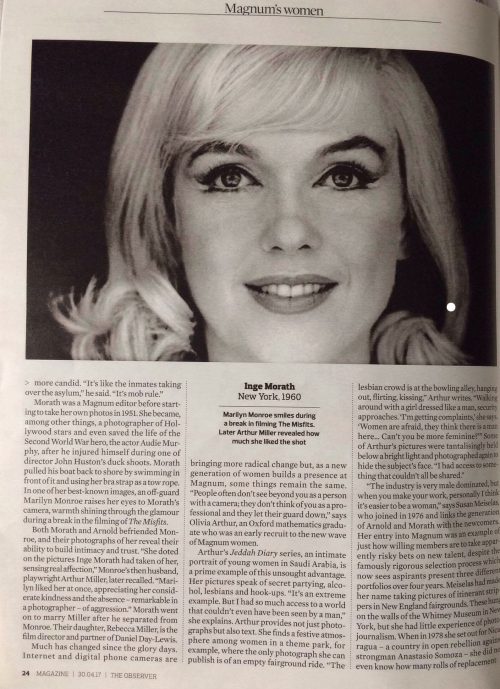

When she was still single, Inge Morath happened to be working on the set of The Misfits for her photo agency, Magnum, and took some haunting pictures of the luminous blonde with the darkness inside.

‘My mother was always very sweet about Marilyn,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘She really liked her. Someone asked her how the marriage between Marilyn and my father was and my mom was like: Oh, very happy. They seemed very happy. Because she wasn’t paying attention.’

If Ms. Miller had to summon her nerve to deal with the lusty and sorrowful side of her father that bubbled up with Marilyn, she also had to summon her nerve to deal with the most disturbing part of the documentary: the institutionalization of her younger brother, Daniel, who was born in 1966 with Down syndrome.

A 2007 Vanity Fair article suggested that Daniel had basically been abandoned in an ‘understaffed and overcrowded’ facility in Connecticut, with his father rarely visiting.

‘I think the Vanity Fair article was written in a spirit of malice,’ Ms. Miller says. ‘They made it seem like he never saw him, which wasn’t true. He did see him. It’s just that it wasn’t, perhaps wasn’t, enough. But you also have to put things in a little bit of historic perspective. There were other families who put their Down syndrome children in institutions. I don’t know. It’s a mystery. And really, finally, in the film, I was ultimately honest with my own limitations and where my knowledge ends. I don’t know exactly what transpired between those people because they never told me. All I know is what my relationship is with my brother, which is great.'”