“The occasion for this restored re-issue is the BFI’s full Monroe retrospective: this is the pained capstone to her mere ten years of stardom, and surely her deepest, most torn-from-the-soul performance … When Gay calls Roslyn ‘the saddest girl I ever met’, the line springs out as the most direct and insightful ever spoken to Monroe on screen, and she reacts to it as if the truth had been grasped at last. The film gets her totally, and despite all the delays and the hospitalisations and the marital spats which made production such a nightmare, she gets it back. After one lengthy hiatus in rehab, [Russell] Metty had to use soft focus to disguise her poor health, which makes her face swim fuzzily in the centre of the screen at times, and this is somehow perfect for a character so unsure of herself.” – Tim Robey, The Telegraph

“Its merits and significance have been exhaustively documented over the years, but The Misfits still has a lot to show us about how we should approach Hollywood today … it‘s the vision of stardom’s pound of flesh. The notion becomes even more potent with Monroe. Marilyn was an idea conceived by several patriarchal forces; but you could see Norma Jean in every moment of her screen time; the sad, abused, ambitious woman struggling to negotiate the compromises of Hollywood – a battle between body and soul. We will never understand her furtive complexities, and that’s why we keep trying. She is the key to understanding so much of the context of the American cinema. When we write about Hollywood, we wrestle with supernovas; we can only catch the debris of their magnificence.” – Craig Williams, Cinevue

“For me, the film is itself a bit of misfit, full of big stagey speeches, contrived moments and some overemphatic performances, but opened out with muscular style by Huston. The faces of Gable, Clift and Monroe together in closeup have a Mount Rushmore look to them.” – Peter Bradshaw, The Guardian

“As the unexpected swan song for Monroe and Gable, it is marred by their death soon afterwards – but it also highlights their isolation in the world of Hollywood … the reason The Misfits is so thoroughly engaging, is because it often hints at a deeper truth. Huston has captured a moment of change and honesty. The story carries weight, as we know the depression and dependencies behind closed doors – and we only wish this wasn’t the final appearances of such unforgettable stars.” – Simon Columb, Flickering Myth

“It is instructive to read Arthur Miller’s account of the making of The Misfits in his autobiography, Timebends. In his account, the film sounds calamitous. His marriage to Marilyn Monroe was breaking up … Against the odds, she gives an extraordinary performance. It’s an artless one that at times seems phoney, but what she does convey in uncanny and febrile fashion is her character’s power of empathy, whether it is her sympathy for the cowboys (Clark Gable and Montgomery Clift) out of kilter with a modern, wages-based world, or for the wild mustangs they plan to kill.” – Geoffrey McNab, The Independent

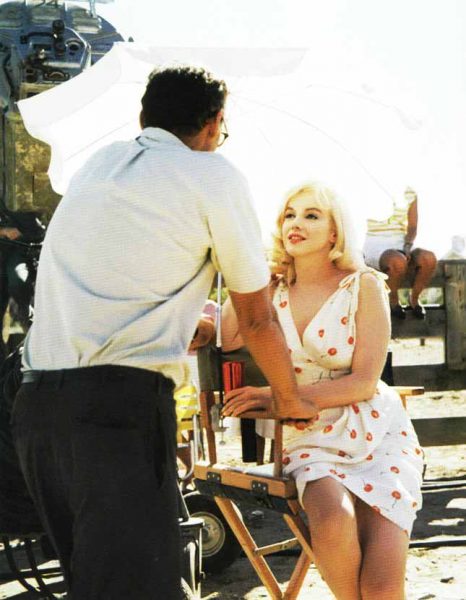

“Bolstered by incredible, career-best performances from Monroe and Gable and the meticulous photography of Russell Metty, it’s a powerful and moving viewing experience. As Monroe and Gable ride off in their truck – neither would live long enough to make another film – they seem to leave behind Hollywood cinema as we know it.” – Tara Brady, Irish Times

“This reissue of what became the last film for both Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe (Something’s Got to Give was unfinished) looks even starker and more jarringly isolated today than it did in 1961 … Monroe and Clift seem to be falling apart before our very eyes, John Huston directs through a fog of bitterness and booze, and Arthur Miller’s script reeks of estrangement and misunderstanding – both literal and literary.” – Mark Kermode, The Observer