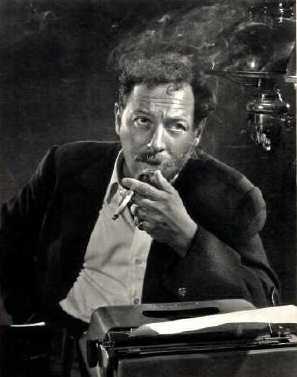

Back in 2012, I posted an extract from Follies of God: The Notebooks, a collection of unpublished writings by playwright Tennessee Williams. Entitled ‘Marilyn Monroe Got What She Wanted,’ the entry was quite cruel. I was disappointed that Williams, who wrote so well about troubled characters and was himself a deeply conflicted man, showed so little compassion for Marilyn.

I was pleased to discover another, more insightful piece by Williams, posted yesterday by editor James Grissom on the Follies of God blog. ‘On the Masks We Wear‘ looks at the gulf between outward appearance and the inner self, using Marilyn as an example.

“Marilyn [Monroe], to use one example, had a literal mask. A lot of people do. Their armor is beauty or strength. Hers was beauty–an almost supernal, lunar beauty. And it took hours–if not days–to create, to manufacture, to maintain. Creams and lotions and unguents and powders and sticks and colorful oils–and then you had Marilyn, the one we all wanted and felt we needed. And she had an identity. An identity of creamy skin and vulnerability. She could face the world with some degree of comfort.”