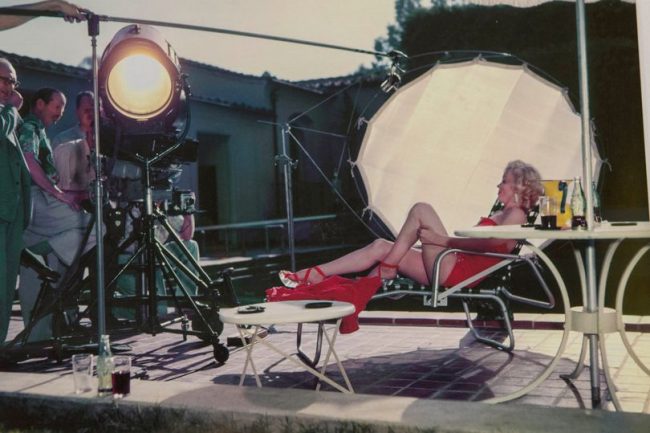

Ted Ryan, official historian for Coca Cola, has been showing The Mirror‘s Emily Setter around the company archive in Atlanta, Georgia. Of particular interest was this rare photo of Marilyn…

“Lolling on a sun lounger in a Coca-Cola red swimsuit and sky-high glass stilettos strapped on with red ribbons, Marilyn Monroe looks the real thing. America’s brightest star fizzed as she posed for a glamorous advertisement for America’s coolest drink in these never seen before images from 1953. Incredibly, for a reason now lost in the mists of time, Marilyn’s sizzling Coke campaign never saw the light of day. Until now.

‘Why wouldn’t you want one of the hottest celebs in the world agreeing to appear with your product?’ laughs Ted Ryan. ‘Why was she not used? The ad was being done on spec, but it was never accepted by the company. We just don’t know why.’

Coca-Cola only learned of the candid behind-the-scenes shots by celebrity photographer Harold Lloyd last year after they were found in, of all places, the archives of NASA. Naturally, Coke snapped them up, and is today letting the Mirror publish them for the first time.”

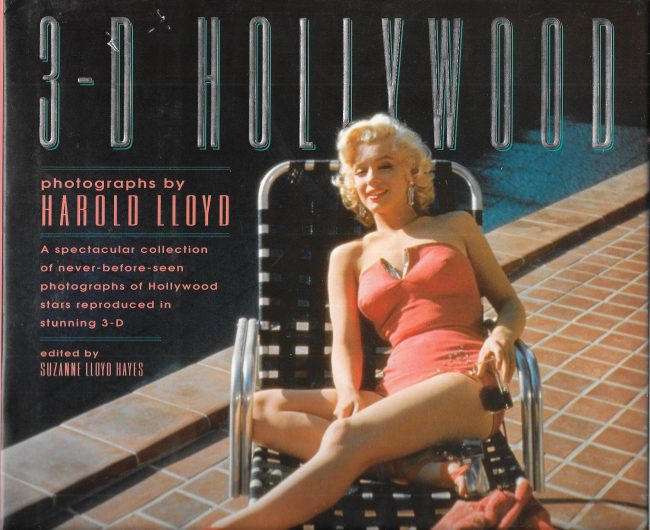

However, this is not the full story, as ES Updates has previously revealed. Marilyn was actually filming a PSA for the US Air Force (not NASA) at Greenacres, the Beverly Hills estate of former silent comedian Harold Lloyd, whose own glamour shots were published in the 1992 book, 3-D Hollywood.

“She visited in 1953 with Jean Negulesco, supposedly to film a dream sequence for How to Marry a Millionaire. This never transpired, but footage of a seductive Marilyn purring ‘I hate a careless man’ was used in ‘Security Is Common Sense’, a PSA for the US Air Force, warning servicemen against revealing military secrets in letters home.

Studio contract stars like Marilyn were routinely asked to endorse products, although she would do so less frequently in later years … the Lloyd shoot does not appear to have been directly connected to Coca Cola – but the tacit promotional value was clearly welcomed, and it has since become part of their glamorous legacy.”