Perhaps more than any other of Marilyn’s major films, the critical reputation of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and its subversive gender politics has grown in recent years, making it both a perfect satire of fifties femininity, and a strikingly modern sex comedy. Back in 1953, it was a box office smash though deemed mere Hollywood fluff, as Christina Newland notes in ‘Male Critics, Female Friendships on Film,’ over at the BFI blog.

“Even when beloved male auteurs turned their attention to female friendship, their films were often not spared. When it comes to women, objectification is more common than nuance. In Howard Hawks’ classic Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), the gold-digging comedy-musical sees its two showgirls turn men into ineffable fools. But a Time magazine reviewer misses the subtext in order to celebrate what he calls ‘the three-dimensional attractions of its two leading ladies’.”

Meanwhile, in the March issue of the BFI magazine, Sight & Sound (with Greta Gerwig on the cover), Hannah McGill’s article, ‘Sister Act’, takes another look at Blondes alongside other movies featured in next month’s ‘Girlfriends’ season at BFI Southbank (where it’s screening on March 1st, and 11th.)

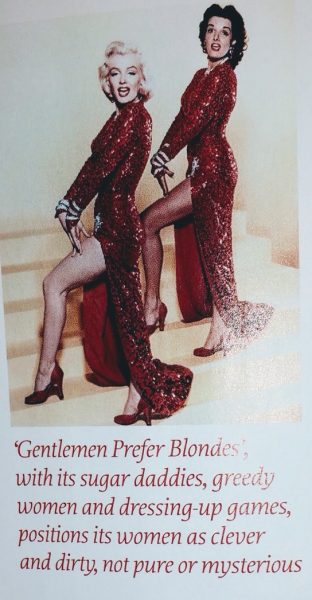

“Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) with its sugar daddies, its greedy women and its dressing-up games, positions its women as clever and dirty, not pure or mysterious; gives them strength specifically through the fact that they prioritise one another over sexual conquests; and plays on the idea that the absorption of stereotypes about women weakens men. The last thing the male characters expect is for Lorelei and Dorothy to team up and outsmart them, because women who look like them are expected to be both disloyal to each other, and unintelligent. ‘I can be smart when it’s important,’ Lorelei notes, ‘but men don’t like it.'”