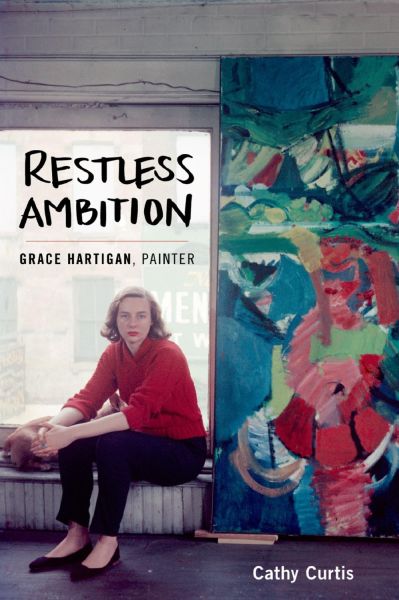

Grace Hartigan was an American Abstract Expressionist painter of the New York School in the 1950s. One of her most famous works, ‘Marilyn’, was created after the death of MM. In a new biography, Restless Ambition: Grace Hartigan, Painter, Cathy Curtis reveals that Hartigan’s interest in Marilyn dated back to the summer of 1957, when she spotted her on vacation with husband Arthur Miller in the Hamptons. She also kept a photograph of Marilyn with author Isak Dinesen (taken in 1959), pinned to her wall for inspiration.

“Marilyn Monroe’s death in 1962 from a barbiturate overdose inspired Marilyn (1962.) Grace floated vivid details in a giddily feminine pink and purple haze; the actress’s gleaming teeth in an open-mouthed smile (from a Life photograph), a wavy blonde lock of hair, a blue eye, white klieg lights, and a gesturing hand emerging from a ruffled sleeve (based on a photograph of a detail from a fifteenth century fresco). Despite the luminous quality of the painting, it has a strangely terrifying quality because of the contrast between the brilliant white arc of Marilyn’s teeth – the only area that seems to push forward into space – and the empty black space inside her mouth.

As a subject for serious art, in an era when popular culture was still held at arm’s length from highbrow culture, Marilyn Monroe was not on a part with Dido and Aeneas. But [May] Tabak had urged Grace not to have any qualms about making a painting about Marilyn. (‘What does abstraction mean if she wasn’t an abstraction?’) At the opening of Grace’s fall exhibition at the Martha Jackson Gallery, [art critic] Harold Rosenberg told his wife that this was the most interesting piece in the show. Grace may also have gained courage from her mentor’s example. [Willem] De Kooning had led the way with his big-eyed, lipsticked Marilyn Monroe (1954), whose oddly chunky torso echoed the colors of her hair and lips. She could also look to Frank O’Hara, whose poem ‘To the Film Industry in Crisis,’ written the following year, evokes the actress ‘in her little spike heels’ in the 1953 thriller Niagara. In ‘Returning’ (1956), he facetiously quotes the film goddess on being a sex symbol.

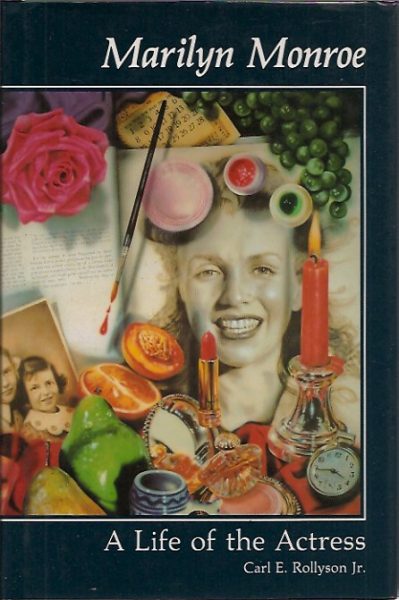

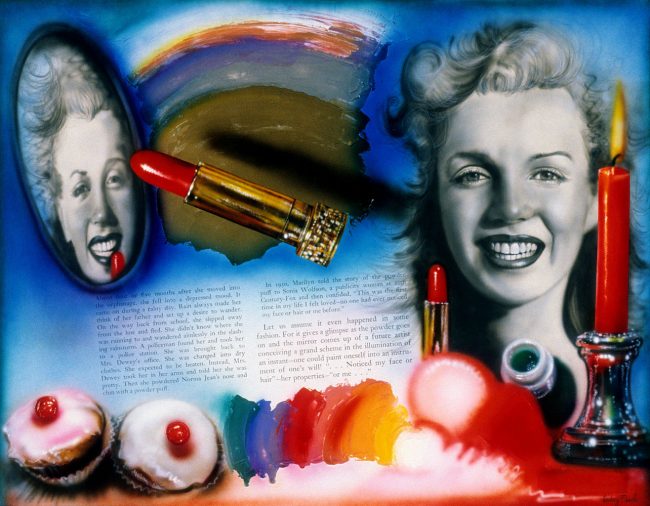

In its wistful sensibility – though, of course, not its style – Grace’s version is akin to Audrey Flack‘s glossy Photorealist still lifes Marilyn (Vanitas) and Marilyn (Golden Girl) from the late seventies. Flack viewed the actress as ‘a symbol for love, the need for love, and the pain of never having enough love,’ identifying with her because ‘she never really got enough love from her mother or father.’ This was an ache Grace knew well. She and Flack were also nostalgic about – as Grace put it – a time when people had a choice of gods and goddesses to worship. ‘We don’t have these now,’ Grace said, ‘so we set up all of these popular culture idols, and we invest them with qualities of love and hostility and so forth.'”

Paint company founder Leonard Bocour – who had once been president of an MM fan club – congratulated Grace on the painting, declaring himself ‘President of the Grace Hartigan Price Fan Club.’ Grace objected to comparisons between her work and Andy Warhol’s ‘big facade,’ adding, ‘my work gets into the woman herself.’