Norma Jeane Baker of Troy, the new short play by Anne Carson, opens at The Shed in Hudson Yards, New York, tonight. However, with decidedly mixed reviews and reported walkouts at a preview over the weekend, the show is off to a rocky start. In his review for Bloomberg, James Tarmy admits it is “not for everyone.” (I’d be interested to hear what a Monroe fan thinks of it …)

“Neither [Ben] Whishaw nor [Renee] Fleming portrays the title character in this equally hypnotic and exasperating production. Or not exactly. When first seen, on a snowy New Year’s Eve in the early 1960s, their characters appear to be a rather anxious businessman (Mr. Whishaw) and the thoroughly professional stenographer (Ms. Fleming) he has recruited to help him work, after hours, on a special project.

That would be the very script of the show we’re watching, which is indeed about Norma Jeane Baker. If you don’t know that Norma Jeane was Monroe’s birth name, I wish you much luck in following this show. Because that’s only the first — and by far the simplest — of the identities attached to Monroe in Ms. Carson’s investigation of the illusion and substance of feminine beauty in a testosterone-fueled world of war.

Helen is Norma Jeane, while her ostensibly cuckolded husband, Menelaus is transformed into Arthur, King of Sparta and New York (referring to Monroe’s third husband, the playwright Arthur Miller).

Norma Jeane is further conflated with another abductee from Greek mythology, Persephone, especially as she was conjured by the 20th-century British poet Stevie Smith. All these variations on the theme of beautiful women held captive by men echo a phrase that is both spoken and sung throughout this production: ‘It’s a disaster to be a girl.’

Now why, you may well ask, is this a tale to be told by a man? Ms. Carson has said that she wrote this monologue with Mr. Whishaw in mind … His ability to cross the gender divide without coyness or caricature turns out to be an invaluable asset in Norma Jeane.

Mr. Whishaw and Ms. Fleming are, against the odds, marvelous. They somehow lend an emotional spontaneity to ritualistic words and gestures, while conjuring an affecting relationship … As might be expected, Ms. Fleming brings a luxuriant, caressing tone to the song fragments … And though it’s a man who narrates — and tries to make sense of — Norma Jeane’s story, it is fittingly a woman’s voice that supplies the aural oxygen in which it unfolds.

You don’t really you need to know your classics or even your Hollywood lore to grasp the thematic gist of Norma Jeane, which ponders the follies of war-making men and their abuses of women. Sometimes Ms. Carson’s conjunctions of figures past and present can seem too both obvious and too obscure. The show’s surprisingly predictable conclusion lacks the haunting resonance it aspires to.” – Ben Brantley, New York Times

“It is a play formed, we learn in the program, through Euripedes’ Helen, which recast the story of ‘legendarily the harlot of Troy and destroyer of two civilizations’ from her point of view, and her sorrow. In the program, #MeToo and that exhaustingly overused phrase ‘fake news’ are both invoked, as well as Carson’s intention to ‘let dark realities materialize dimly’ in particular sections of the play.

Well, Norma Jeane Baker of Troy can claim success on that score at least. The set, far too far away from the audience, feels like a retreating photograph. On it, you had two otherwise-wonderful performers, Whishaw and Fleming, playing within what first looks like the office of a gumshoe.

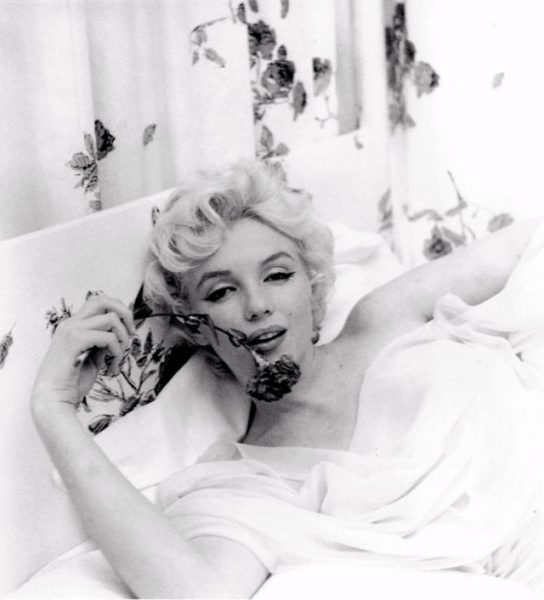

It’s New Year’s Eve, turning to New Year’s Day, 1963, with fireworks booming outside like bombs. Whishaw’s character has a mood board of sorts, and—it turns out—is not a detective, but a screenwriter working on a film project that is a meditation on both Marilyn Monroe (who died the previous year) and Helen of Troy.

The script drifts, utterly unmoored, between the two, their lives, ambitions, beliefs, and the men, dramas, and in Helen’s case war. Misogyny, ambition, and marriage pulse as themes.

As the play progresses, Whishaw, darting here and there, gradually changes into Monroe—via breast and buttock padding, make up and a wig—until finally putting on a dress that recalls the famous flowing white dress Monroe wore in The Seven Year Itch. As Monroe, we hear of the actress’ private pain; there are pills, a champagne bottle that stubbornly refused to pop open (how symbolic that seemed on Saturday night), and then death.” – Tim Teenan, Daily Beast

“Ben Whishaw plays Marilyn/Norma Jeane, or rather he plays a young man in suit and tie (costumes by Sussie Juhlin-Wallen) who dictates a modern update of the Euripides play to a stenographer (Renee Fleming) on New Year’s Eve, 1963. The two of them sit at desks in a very film noir office (set by Alex Eales, the minimal lighting by Anthony Doran) before Whishaw begins to dress up like Marilyn Monroe in The Seven Year Itch, complete with her signature white halter-top dress and ukulele. Ukulele? Maybe Whishaw’s drag persona borrows it from Sugar in Some Like It Hot, but then, inconsistency is Carson’s trademark.

Whishaw’s young man first mentions Marilyn in her preproduction days on Clash by Night where MGM is helping to wage the battle of Troy — even though RKO released Fritz Lang’s 1952 classic.

Whishaw often dictates that Marilyn ‘enter as Truman Capote’ before imitating that writer’s high-pitched voice. This Marilyn also has a young daughter, Hermione, which is also the name of Helen’s long-lost daughter. Marilyn’s Hermione lives in New York City, and occasionally Pearl Bailey makes an appearance there.

Carson plays slow and loose with the Monroe legend, and in press materials, she connects her subject to the #MeToo movement. #WhatAgain? is more like it.” – Robert Hofler, The Wrap

“Carson’s interest in a multitude of genres and in mixing registers is on full display in Norma Jeane. Many of Whishaw’s lines, like “She’s just a bit of grit caught in the world’s need for transcendence,” are gorgeous and heightened, like poetry; the references tossed around range from Persephone to Pearl Bailey; the set is naturalistic, but the action happening on it is mythic and strange. We’re ostensibly watching two people write a play within a play about Marilyn Monroe, but they’re also investigating the Trojan War, and (in Fleming’s case) delivering operatic sung-monologues about rape and Greek tragedy, and (in Whishaw’s case) getting into full, Seven Year Itch Marilyn drag. It’s about gender and pain and war and mythmaking—all interesting, but wordy and not easy to follow. If my attention wandered off at any point, at least the Griffin’s beautiful raised stage and sleek all-black look gave me plenty to appreciate.” – Amanda Feinman, Bedford + Bowery

“Carson entwines the stories of Norma Jeane—the sweet-faced pinup girl who would one day be recast by Hollywood, then by life, as Marilyn Monroe—and Euripides’s Helen … Here Norma Jeane tells the story of how her husband Arthur, king of Sparta and New York, invaded Troy reportedly to rescue her while she, safely stowed at Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, is reduced to ‘box office poison.’

For ninety minutes, Fleming and Wishaw—a luminous duo if ever there was one—did their best to make things interesting, but the scenario they were given was oppressively thin. The always marvelous Wishaw spoke as Fleming typed along, recording him, singing passages to him, with him, less amanuensis than an alighted angel, a tender force. As the Steno paper spilled across the desk and piled up on the floor, Wishaw gradually swapped his suit for a girdle, a bra and some padding, a platinum wig, and a white halter dress, becoming ‘Marilyn Monroe’ (a drag, it must be noted, first worn by Norma Jeane).

This production of Norma Jeane woefully never transcended the appearance of an exercise, never bloomed into a total work, in large part because it backed away from devising compelling and imaginative solutions to the challenges Carson poses: how to revise a famous tale to reveal the false truths that shape and warp women and men; how to pave space for possible collisions between stage and screen; how to tickle and tug at the thin membranes that separate person from persona, performer from icon.”

Jennifer Krasinski, Artforum