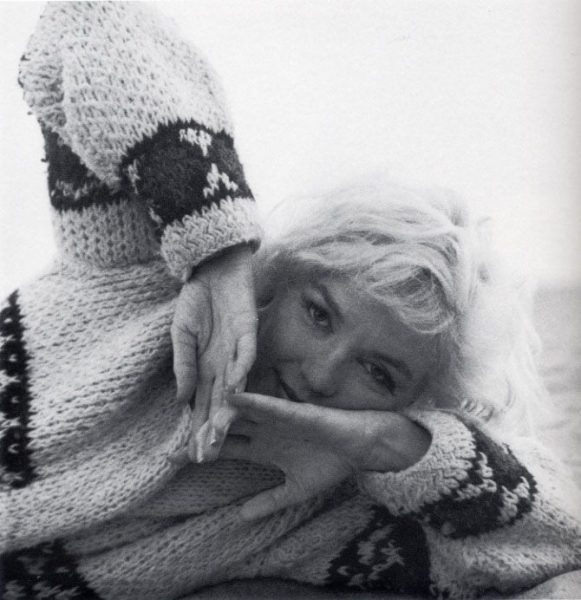

In their new book, Cinema ’62, Stephen Farber and Michael McClellan make the case for 1962 as an all-time great year in film – citing The Miracle Worker, To Kill a Mockingbird, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane among its finest releases. While Marilyn’s abandoned last movie wouldn’t make the grade, the authors have referenced another prestigious title from 1962 first offered to her. (In John Huston’s Freud, starring Montgomery Clift, her role was played by newcomer Suzannah York – more details here.)

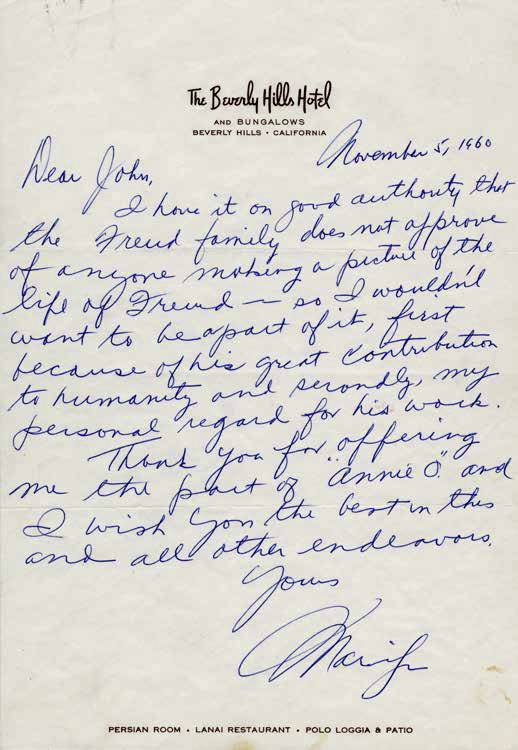

“Marilyn Monroe, the greatest star of the 1950s and early 1960s, was known not only for her sensual image and temperamental behaviour on the set. She was also, like many actors of the era, a passionate devotee of psychoanalysis who spent years sampling the wares of a series of fashionable doctors. In 1960 John Huston, who had directed her in one of her best early films, The Asphalt Jungle, and in her latest picture (which would turn out to be her last), The Misfits, offered her a key role in his ambitious tribute to the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud. Marilyn was intrigued by the opportunity to tackle such a demanding dramatic role, but she ultimately turned it down, partly at the urging of her current analyst, Ralph Greenson, a close friend of Anna Freud, who was vehemently opposed to the idea of a Hollywoood picture about her sainted father’s life. In a letter to Huston dated November 5, 1960, just after The Misfits finished shooting, Marilyn declined the role. ‘I have it on good authority that the Freud family does not approve of anyone making a picture on the life of Freud,’ she wrote, then added that she could not be involved in the project, in part because of ‘my personal regard for his work.'”

Elsewhere in Cinema ’62, the authors discuss Marilyn’s demise and the loss felt within the movie industry and beyond.

“Tragically, Hollywood found its most luminous star permanently dimmed in August 1962 when Marilyn Monroe’s sudden death at the age of thirty-six rocked the movie industry and saddened fans worldwide. Monroe had been fired in June from George Cukor’s presciently titled and unfinished Something’s Got to Give after delaying production with her erratic behaviour. The emerging New Hollywood could no longer indulge its eccentric stars, not even the last great creation of the old studio and star system. Monroe had been the highest-ranked female box office draw three times in the mid-1950s but yielded that spot to Elizabeth Taylor and Doris Day by the start of the 1960s, when she dropped out of the poll. However, Monroe would soon be immortalised as a cultural and screen icon, while her passing symbolised both the decline of female stars in the Hollywood firmament and the demise of the classical studio era. Fortunately, thanks to the creative vision of some veteran filmmakers as well as some brand-new voices, the cinema of 1962 remained as vital as ever.”