Among the upcoming screenings of the newly restored Some Like It Hot is an intriguing double bill. At 1:30 pm on December 16, the 1959 classic will be screened at London’s Regent Street Cinema, followed by It Should Happen To You (1954) at 3:50 pm. Not only does Jack Lemmon appear in both films, but It Should Happen To You also stars Judy Holliday, the blonde star who, alongside Marilyn, was one of the leading comediennes of the era.

The film was directed by George Cukor, who later worked with Marilyn in Let’s Make Love and the unfinished Something’s Got to Give. Judy stars as an out-of-work actress whose life is transformed when she rents a billboard to advertise herself. In his first major film role Lemmon plays a photographer, while Peter Lawford – another figure from Marilyn’s life – is cast as a rather caddish businessman.

A native New Yorker, Judy Holliday became a star on Broadway with her role as Billie Dawn, a gangster’s moll who falls in love with a straight-laced journalist hired to educate her, in Garson Kanin’s Born Yesterday. Kanin later said that a young Marilyn had auditioned for the big-screen adaptation, but the role was ultimately reprised by Judy.

The two actresses – who both battled ‘dumb blonde’ typecasting, finally met in 1956, as Martha Weinman Lear revealed in a 1988 article for Fame magazine. (Sadly, Judy Holliday’s career would also be cut short when she died, aged 44, of breast cancer in 1965.)

“Thirty blocks downtown, a billboard dominated Times Square. This was in 1956, a cave age, but you remember that billboard. Even if you weren’t born yet you remember that billboard: Marilyn Monroe, starring in The Seven Year Itch, loomed twenty feet tall … in what was, and remains, one of the most powerful images ever to come out of movie advertising.

A few blocks east, more peekaboo: Judy Holliday, the Funny Girl of her day, was transforming herself nightly into just that paper doll, and packing them into the Blue Angel supper club with her impersonation — never mind the makeup, it was an act of brains and will, and it was brilliant — of Marilyn Monroe.

It was my first job, at Collier’s magazine, doing my own impersonation — eager researcher playing cool reporter — and yearning for some epiphanic professional moment. It came…

Leonard Lyons, gossip columnist for the old New York Post, was strolling down Fifth Avenue with Holliday one day, or so he reported, and they ran into Monroe. Reality and illusion head-to-head; how avidly the two must have eyed each other! Introductions were made. Someone said, ‘we ought to get together,’ and the women arranged to have tea at Judy’s apartment in the Dakota, Collier’s to record the event for some ravenous posterity. I was sent to take notes.

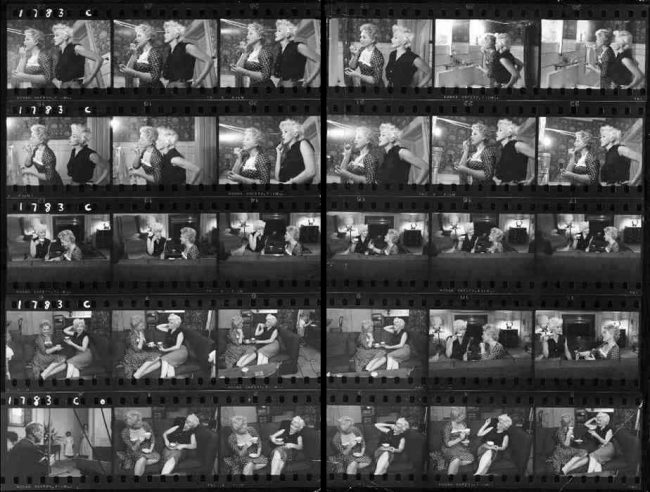

The photographer Howell Conant, was all set up in the living room. The appointed hour came, and no Marilyn. A half hour later, no Marilyn. Judy grew tenser. Finally, after an hour, a person arrived, and it appeared that this person was Marilyn Monroe.

Time has done nothing to dim the details: She wore a black cotton shirt, sleeveless, a brown cotton skirt and flats. There was a big grease stain on the front of the skirt. The belly protruded. The legs were covered with bumps and scabs, which she kept scratching. The platinum hair showed dark at the roots and, when she raised her arm, I saw a luxuriant dark undergrowth. This was before political statements; we were all shaving our armpits. She looked…tatty, a bit. Only the voice was unmistakable, pure sigh (was it afraid to be heard or demanding that we lean in to listen? I have never been sure). Only the skin, which was truly luminescent, would have stopped you in the street.

‘We were getting worried about you!’ Judy cried. Her voice shook, I think with wrath.

‘I’ve got mosquito bites,’ the goddess whispered, and bent to scratch yet again. And though the sequitur escaped me, I instantly and utterly forgave her for being late.

She wanted to makeup her face. Then the two of them thought that it might be fun for Judy to put on her Marilyn face first, while Marilyn watched in the mirror. They began, and it was impossible. Marilyn guided graciously, with soft breathy urgings: ‘Mm, make the eyebrow a little pointier … Yes, that’s right …’ But Judy couldn’t do it. She did it every night, but here, now, in the presence of the real thing…who did not herself look much like the real thing, which gave rise to problems of philosophic scope, because who or where was the real thing? Was it here, in this sweetly scruffy presence, or was this a mere mortal metaphor for the real thing, which was up there on the billboard?

‘Well, uh…’ Marilyn began, and giggled, craning her own head back gingerly, as though trying to ease a stiff neck. And that was when I finally saw, quick study that I was, that both women had the same problem: They were both straining to impersonate Marilyn Monroe.

So they tried it the other way. Marilyn would make up first. ‘Oh, I look awful,’ she said, but in the mirror she took on authority. She set to work with that total Teutonic dispassion of models, a touch of shadow here, a dab of highlight there, an extravagance of mascara, an artful swirling of hair around the roots. I waited, wild with curiosity — Judy too — for the transmutational touch, peekaboo! But Monroe was doing no magic tricks; she was simply spiffing up what she had, as we all do.

And then came this remarkable moment. The child, Jonathan, appeared in the doorway. Judy bent to him and took his hand. ‘Jonathan,’ she said, ‘do you remember that lady we saw in the movie, Marilyn Monroe?’ The cherub nodded. ‘You want to meet her?’ Again he nodded, wide-eyed. ‘Jonathan,’ she said, and her hand swept across the room — flourish of trumpets, roll of drums — ‘this is Marilyn Monroe.’

Marilyn was standing. She had just hitched up her skirt to pull down the blouse from underneath. She looked at the little boy, and he at her, and in that instant it happened. She metamorphosed … And the head tilted easily back, the eyelids closed down, she licked her lips, became that myth and smiled full into the child’s face and sighed, ‘Hi-iiii.’

Conant shot hundreds of exposures that afternoon; not a single one of Marilyn was bad, and most were splendid. Ultimately, what one saw in the room did not matter. Her face, as they say of certain faces — as they first said of Valentino’s face — made love to the camera.

The pictures were never published because Collier’s, soon after, went out of business. The one shown here was taken as a souvenir for me, and I have never looked at it without remembering that moment of her transmutation, and wondering: What on earth she thought she was doing? And it must be that she simply had not thought at all, but had simply heard the bell and gone on automatic. If it was male it was her audience, her element, and she would play to it. This is a gift. It is not necessarily a gift that makes good actors, but it almost invariably makes great performers.”