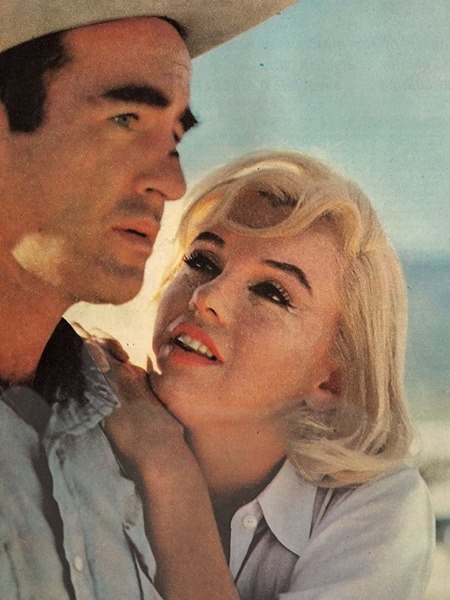

Following a recent screening of The Misfits for students at Stanford University, Carlos Valladares has reviewed Marilyn’s swansong for Stanford Daily.

“The Misfits comes out at the tail-end of the classic Hollywood era (1961), and it shows. The photographers who drifted on and off the set (Eve Arnold, Bruce Davidson, Henri Cartier-Bresson) showed off Monroe, Clift, Gable in all their un-Glamour, in a starkly honest look that would have been unthinkable in the studios’ heyday … The editing is odd and erratic, but these glitches actually contribute to its depth. At one point, Monroe’s lips go out of sync with her voice. At another, Monroe’s close-up is interrupted by a blurry soft focus. She has none of the leering, near-pornographic dazzle of her 1950s promotional photos. Here, the camera looks as if it were just crying, doing a terrible job at wiping away its tears, overwhelmed by the state of Marilyn.

The Marilyn performance is so brave precisely because, despite the odds, she survives … It is when the men, after all their hard work and physical exertion, decide to shoot the wild horses they just captured, selling their meat for a few lousy hundred bucks. Suddenly, Monroe darts off into the distance and screams … the exact catharsis needed to make us care again about the sanctity of human beings. The camera hangs far back in an extreme long shot, making me feel Rosalyn’s insignificance, and, contrariwise, Monroe’s strength. It’s a rare instance where Rosalyn/Monroe has privacy to herself. Huston wisely does not go in for a typically Hollywood close-up that would show her breakdown and emotional turmoil with dramatic, lurid tastelessness. The camera cannot go in for a close-up. To do so would completely negate the scene’s point: the breaking out of a woman from her banality. She screams: ‘ENOUGH.’

The dialogue in this remarkable scene (perhaps the climax of Monroe’s acting career) also predicts Monroe’s eventual suspected fate … She could just as well be talking back to Arthur Miller (and the viewing public — us) as she is to Gable, Wallach and Clift. It’s an amazing example of an actor taking back her agency in a narrative that, at first glance, seems to float above the actors.”