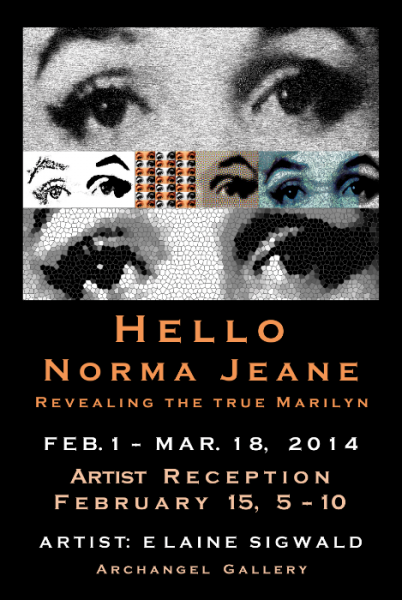

‘Hello Norma Jeane’, a new exhibition of 25 photographs and digital manipulations by artist Elaine Sigwald – each based on Marilyn’s own words – is now on display at the Archangel Gallery in Coachella, until March 18.

Marilyn Monroe 1926-1962

‘Hello Norma Jeane’, a new exhibition of 25 photographs and digital manipulations by artist Elaine Sigwald – each based on Marilyn’s own words – is now on display at the Archangel Gallery in Coachella, until March 18.

Perhaps the most celebrated child star of all time, Shirley Temple, died on Monday, February 10th. Writing for Bust, Alanna Bennett notes that in her teenage years, Shirley looked a lot like the then-unknown Norma Jeane Baker.

“I mean, look at them. It could be chocked up to 1940s/1950s styles — the hair style is certainly that, and makeup trends also probably played a part — but there’s also a definite shared heart-shaped face, lip and eye shape, nose curvature, etc.

What’s interesting to me here is that these women did not spend the majority of their lifetimes resembling each other. It appears that they did, however, sort of meet in the middle: Temple spent her young childhood as one of the most famous people in the world, then went on to live a relatively ‘normal’ life thereafter; Monroe had that relatively ‘normal’ life roughly until her breakthrough in 1948, when she was twenty-two. Temple was also born only two years after Monroe, in 1928.

Both women made a big impact on the culture of their time — generations of women spent their childhoods wanting to be Shirley Temple, and their adolescence or adulthood yearning to be Marilyn Monroe. They obviously had very complicated lives in large part because of that, but there’s something calming in seeing their similarities.”

Temple delighted Depression era filmgoers, and some have said she helped to save Twentieth Century Fox from bankruptcy during the 1930s. Marilyn would later become the same studio’s most bankable star of the 50s.

Shirley Temple Black retired from acting in 1950, aged 22, and later became a US diplomat, travelling the globe under successive Republican administrations.

Marilyn’s biographer, Carl Rollyson, speculates that ‘it was the portrayal of Shirley as waif and orphan that appealed to Marilyn and formed the basis of some of Marilyn’s stories about her childhood.’

In later life, however, Marilyn did not always welcome the comparison, as this extract from journalist W.J. Weatherby’s Conversations With Marilyn reveals:

“‘I read your article about me,’ she said. ‘Who’s Mrs Patrick Campbell?’

I had described her in the article as a cross between a theatrical grand-dame like Mrs Campbell and a child star like Shirley Temple.

She beamed when I told her, but added that she took a dim view of being even remotely compared to ‘Lolita Temple.’

‘Sorry. Now that I know you better, I wouldn’t compare you to anyone.'”

German advertising agency Preuss und Preuss have found a novel way to promote Susan and Bruno Bernard’s Marilyn: Intimate Exposures. Tacky, or cute? Watch the ad here, and then decide…

Marilyn’s estate is suing the Marilyn Monroe Cafe chain for non-payment of photo licensing fees – a total of $18.35 million, reports TMZ. This sum is the remaining amount on a 20-year contract, in which the cafe owners agreed to pay $1 million annually. (Interestingly, at the time of writing, the cafe’s official website was down.)

Seward Johnson’s giant statue, ‘Forever Marilyn’, has been bathed in red light to raise awareness for the American Heart Association throughout February in Palm Springs, reports the Desert Sun.

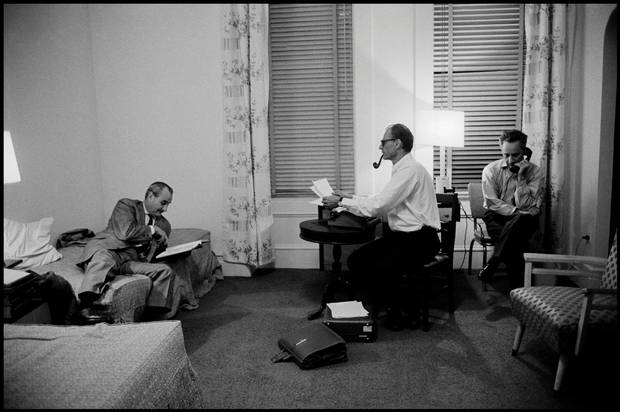

Inside the Dream Palace: The Life and Times of New York’s Legendary Chelsea Hotel is a new book by Sherill Tippins. Among many other events, the author chronicles how Arthur Miller lived at the hotel after divorcing Marilyn Monroe, and wrote After the Fall, a thinly-veiled portrait of their marriage, which opened in 1964 amid intense controversy.

“Miller should have realized, as Warhol had demonstrated so efficiently with his Marilyn exhibition less than two years before, that New York audiences would identify with Maggie, or at least with the vulnerable spirit within themselves that she represented. Her story – her desires and her victimization – was their story. That night in the theater, it was almost as though Marilyn had stepped through the playwright’s dialogue to take command of the audience herself.”

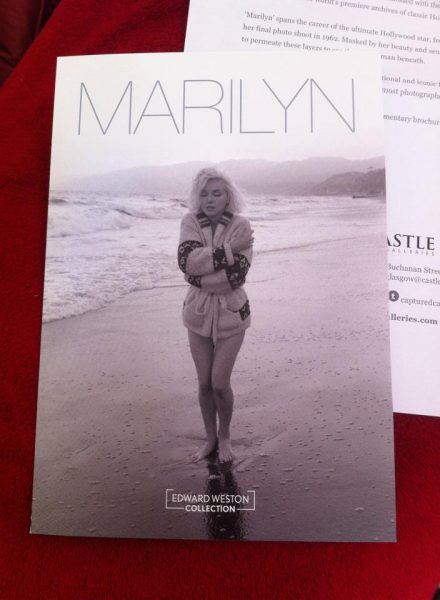

A portfolio of eight limited edition prints of Marilyn, taken from the Edward Weston Collection – including photos by Andre de Dienes and George Barris – can now be viewed (and purchased, if you can afford it) at branches of Castle Galleries across the UK, where brochures are also available. A review of the display can be read at Burlesque Bible.

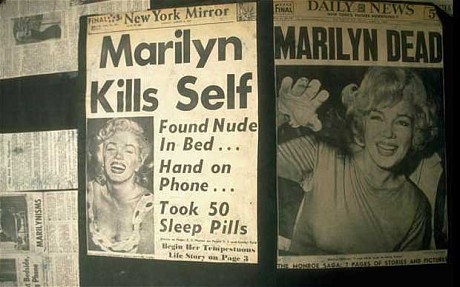

In today’s Telegraph, Gaby Wood takes a critical look at the prurient news coverage of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman‘s death from an alleged heroin overdose last weekend, comparing it to other Hollywood tragedies, including Marilyn’s:

“‘Hollywood has always been like this,’ someone said this week with a shrug, ‘look at Marilyn Monroe.’ It’s true that there have always been scandals. It’s true that the misinformation surrounding Monroe’s death was handled so shabbily, and by so many nefarious parties, that it became another form of assault. But as it happens, the case of Monroe is also instructive, and proof that things were not always this way. Because she was, at the time of her death, the product of the immediate post-studio system.

You might say she was unique: that no one could compete with her as a sex symbol; that the tragedies of her personal life made her especially vulnerable; that had she not been linked to the president the damage limitation would not have been so brutal.

But look at the year she died: 1962. The studios, who had controlled everything, and who had manufactured Marilyn out of Norma Jeane Mortenson, had collapsed at the end of the Fifties. The old orchestrators of official stories had been deposed, and a scene that would once have been carefully re-scripted became a free-for-all.

There were, instantly, lurid reports – even now, 62 years after her death, it remains one of the most raked-over episodes in Hollywood history. The time and cause of death have never been properly proven; her sheets were thought to have been changed before police arrived; autopsy photos were released; several parties claimed to have visited her bedroom and removed evidence.

Her housekeeper, psychiatrist, press agent and lovers were all implicated. And although Monroe wasn’t the first star to have been abandoned by the Hollywood system, she was certainly the biggest.”

However, as Marilyn’s biographer Carl Rollyson has pointed out, both Monroe and Hoffman deserve to be remembered for their immense talent, and not merely their untimely demise:

“I don’t think Marilyn ever did hard drugs, and I don’t think her death has much to tell us about Hoffman’s, except that as performers they were under terrific pressure to always be ‘on.’ Unlike Hoffman, Marilyn was still a contract player, even though she had her own production company, as did Burt Lancaster and others. The point about her is that she is a great transitional figure between the old Hollywood and the new. She was part of an emerging new paradigm that actually began in the late 1940s when the studios were forced by court order to divest themselves of movie theater ownership and, thanks to another lawsuit, the old studio contract that amount to indentured servitude was declared illegal. I think Marilyn’s instincts were right. If only Charlie Feldman (her agent for a while and producer of The Seven Year Itch) had pushed the studios a little harder instead of wanting to play the producer’s game, he might have helped Marilyn more. The other option was if someone had pointed out to Marilyn that she ought to go to Europe. After all, the French and the Italians were giving her awards. Maybe someone did point that out, but I don’t think it was made abundantly clear to her.”

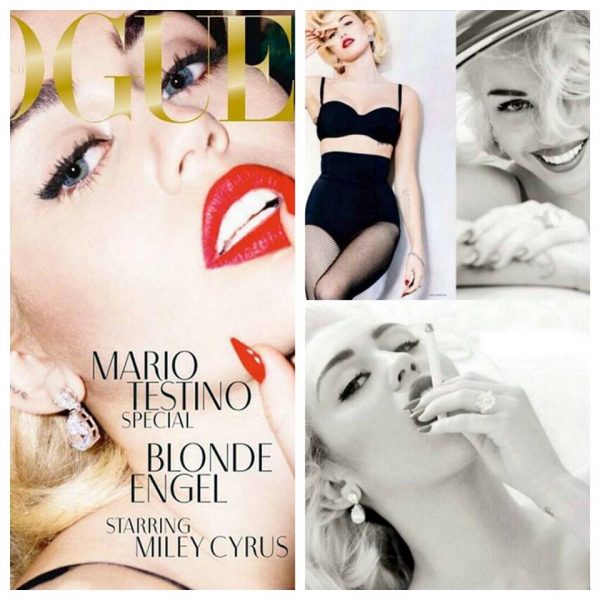

A new photo shoot for German Vogue, featuring pop star Miley Cyrus, is being widely tagged as Marilyn-inspired. However, as Pink is the New Blog has noted, Miley more closely resembles Madonna during her Blond Ambition phase. Madonna recently dueted with Miley, who cites her as an influence. Marilyn via Madonna, perhaps?

How to Marry a Millionaire will be screened next Tuesday morning (10 am) in the SCERA Center for the Arts‘ XanGo Grand Theatre in Orem, Utah, as part of their Cinema Classics series.